SHANTI GIOVANNETTI-SINGH discusses the significance of cultural destruction in the exhibition Culture Under Attack at the Imperial War Museum

On 15th April 2019, a structure fire tore through Notre Dame de Paris cathedral. The flames spread almost as fast as the media attention which mourned the destruction of one of Europe’s most venerated monuments. As the fire consumed the spire of this 12th century UNESCO world heritage site, donations from both France and the international community flooded in, raising a total of £650 million within ten days. Five people were injured. There were no fatalities.

Six days later, on Easter Sunday, a series of terrorist attacks in Sri Lanka left 500 injured and 259 dead. The eight coordinated attacks targeted churches and religious sites throughout the country, notably St Anthony’s Shrine in Colombo, as well as luxury hotels and housing complexes. Despite a campaign launched by the red cross to raise $50 million in aid of the victims, the financial support that Sri Lanka received paled in comparison to that of Notre Dame de Paris.

These two events, occurring less than a week apart, draw attention to a bitter, yet compelling phenomenon regarding social perceptions of tragedy. Westerncentric media focus is one of the reasons why the attention the fire of Notre Dame received overshadowed that of the Sri Lankan bombing. A further reason, however, can perhaps be explained by considering how we understand direct attacks on humans as opposed to those that destroy cultural monuments and artefacts. People are becoming increasingly numbed to assaults on humanity. Each news story becomes blurred, resuming its role in the stagnant repertoire of the media — famine, , war — casuing victims to morph into figures in an ever-growing death count. Conversely, attacks on cultural artefacts and monuments remain shockingly cruel to us. Human tragedies are accepted as sad, but inevitable realities, whilst events like the destruction of the Library of Alexandria, or the bombing of the Canterbury Cathedral, are seen as rare and critical attacks on our intellectual history and identity. The destruction of these artefacts remind us of a terrifying truth: the perishability of the mark we leave behind. Buildings and monuments represent legacies which intend to vividly translate the stories of the past to the present by providing communities with a shared sense of identity. Outliving our ancestors, these artefacts continue the tales that would otherwise be forgotten time. But what happens when these cultural sites are obliterated? This concept is explored in the exhibition Culture Under Attack at the Imperial War Museum.

Culture Under Attack consists of three rooms: ‘What Remains’, ‘Art in Exile’ and ‘Rebel Sounds.’ The exhibition deals with both the role of art and national heritage in times of conflict, but also considers how war can reformulate social identities. The exhibition’s emphasis on the connection between the individual and the cultural is foregrounded by an interactive questionnaire at the end of each room. By answering a series of questions relating to the value of art, the visitors essentially become part of the exhibition themselves, as statistics formed by their responses are displayed on a large screen .

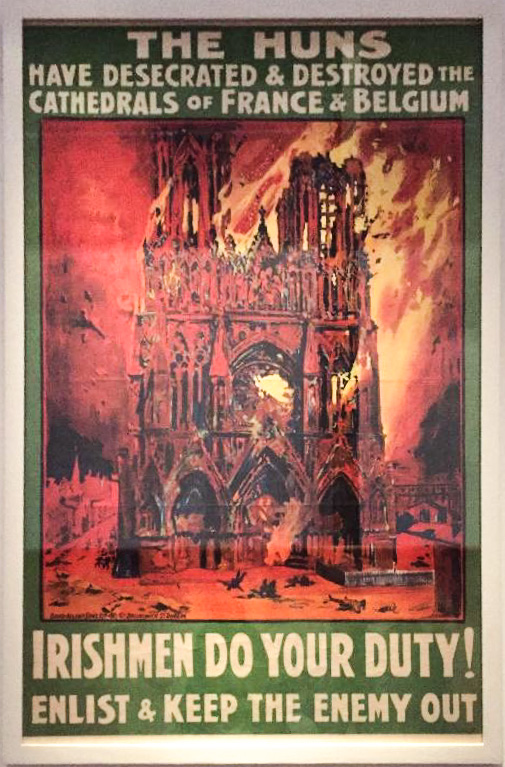

In the first room, entitled ‘What Remains’, the role of national heritage in forming cultural identity is explored. In times of conflict, attacks on a community’s national heritage are often used as a form of cultural, intellectual, and psychological warfare. By destroying and removing monuments and artworks of significance to a specific culture, the enemy removes all traces of that community’s cultural presence, committing ‘culturcide*’. One of the examples from the exhibition is the looting and destruction of Jewish artefacts during the Holocaust. In an attempt to obliterate both the Jewish people and their cultural and intellectual history, the Nazis strived to remove all traces of Jewish artistic and cultural heritage from European society. Other examples include the attack on the ancient city of Palmyra by the so-called Islamic State (IS), and the Taliban’s destruction of the Bamiyan Buddhas in 2001. The severity of ‘culturecide’ is recognised by the United Nations, who categorise it as a violation of human rights, due to the detrimental psychological effects of witnessing your national heritage being erased.

The loss of art and culture during war, however, is not exclusively the result of ‘culturecide’. During times of war, the choice of which artworks to save and which to risk can radically alter the way in which a nation is perceived. This idea is contemplated in the second part of the exhibition: ‘Art in Exile’. As soon as you enter the exhibition, you are faced with 60 photographs with rankings I-IV, where I denotes artworks of highest cultural significance and IV lowest. This represents the challenging decision undertook by the staff at the IWM who could only evacuate 1% of the museums vast collection during World War II. At the bottom of a picture, a plaque asks visitors whether they agree with this classification. This incites the question of whether the value of art can be truly determined, and if so, by whom and using which parameters. The artists chosen, the subjects depicted, and the mediums used have a direct impact upon how a nation’s cultural history is perceived. Therefore, the curator’s choice is of the utmost importance. Some of the choices reflect the institutional biases which influenced the perceived value of art. Out of the 281 works of art evacuated, not a single piece was by a female or a person of colour. Moreover, the art of many 19th-century artists were prioritised over the works of contemporary artists, such as Paul Nash, which tend to be valued more in the current artistic canon.

Whilst many pieces of art have been lost during conflict, various artists have used culture therapeutically to attempt to heal some of the impacts of war. The third section of the exhibition, ‘Rebel Sounds’, illustrates how art is used to rationalise, react to, and resist conflict and oppression. This multisensory section, consisting of recordings, interviews, and explanations, follow four very different bands. Beginning with Irish punk during the Troubles in the late 1960s, the exhibition then covers the role of German swing in the 1940s, Serbian Techno in the Yugoslav Wars in the 1990s, before finally focusing on African Desert Blues which emerged from the civil war in Mali in 2012. From the smooth saxophone of the German Swing Kids whose love of Jazz during the Third Reich, to the gritty howl of The Undertones who brought Irish punk to a nation deemed too dangerous for international artists, each tone is a physical manifestation of how war shaped culture and therefore national identity.

From the conversion of the Mosque of Seville into the largest gothic cathedral in the world, to the protest songs of Bob Dylan, war and conflict have completely shaped and redefined cultural and societal landscapes. The fascinating connection between the two is encapsulated in the Culture Under Attack exhibition at the IWM, the impact of which strongly resonates due to its topical nature, even long after you have visited.

Culture Under Attack is open until 5th January 2020 at the Imperial War Museum. Find tickets and more information here (http://www.iwm.org.uk/seasons/culture-under-attack)

*culturecide: The systematic destruction of a culture, particularly one unique to a specific ethnicity, or a political, religious, or social group. Alternative form: culturicide, culturcide Source: https://www.wordsense.eu/culturicide/

Featured image courtesy of the Imperial War Museum.