STELA KOSTOMAJ explores class origins in film and the phenomenon of poverty porn.

When looking at the theme of “origins” in film, an important aspect that often gets overlooked between the lives of the director and writer(s) and the stories, lives and experiences of their characters. Far too often, we feel as if the story is told from the perspective of an outsider looking into a life they neither can nor do know, because it is so detached from their reality. This is particularly prevalent when it comes to filmmakers tackling poverty.

So-called ‘poverty porn’, also known as development, famine or stereotype porn, is a specific type of media, often film or television, which exploits the condition of marginalised people, in order to generate the necessary sympathy for selling said media.

Sean Baker’s The Florida Project (2017) is a brilliant example of this, as it foregrounds the nuances of aestheticizing working-class life. The story follows children living on the outskirts of Disney World Florida, where seedy motels house families living on the poverty line in small rooms with just one bed. The camera work uses eye-level shots from the child’s perspective, so adults are always towering over the shot. The motels themselves are hyper-chromatic. The story, however, directly contrasts the beautiful setting; oppressed by mounting bills, the mother of these children turns to sex work in order to supplement her income. The movie is undeniably beautiful and heart-breaking, whilst still managing to be funny and playful. It delves into the complexities of income, motherhood and childhood, whilst simultaneously feeling subtle, never pointing to anyone’s actions with condemnation or contempt. It quite simply observes life and cleverly transcends the stamp of it being labelled ‘poverty porn’ as it is delivered from the child’s gaze. It portrays the environment through the eyes of a child: innocent, colourful, exciting – a place to explore and to play in. Moreover, it escapes the full brunt of critique by not having a character arc dependent on a ‘pull yourself up by the bootstraps’ message in the same way City of God (2002) does.

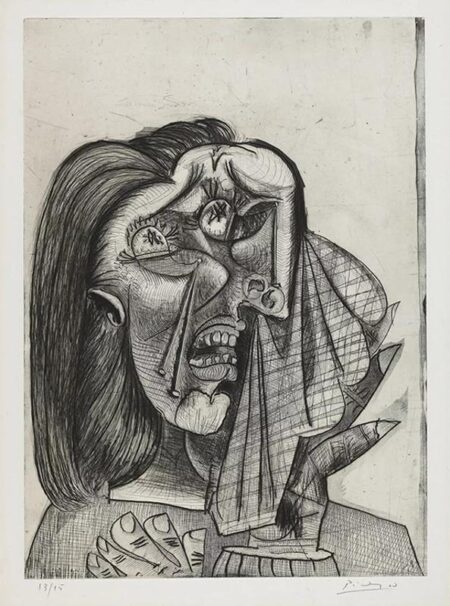

A highly contentious film that prompted a wave of discussions about poverty is Danny Boyle’s Slumdog Millionaire. Its 2008 release saw the portrayal of the Juhu slums of Mumbai, which some felt elided the pride and dignity of the communities living there. Instead of complex characters, Boyle relied on stereotypes, showcasing children wading through rubbish tips and families living in squalor. Some believed that the prioritised entertainment and commercial success over pedagogy and realism. It was a source of national pride for many people in India, as many Indian actors were given a global audience through the success of the film. However, it is worth noting that the title itself is inherently classist and offensive, as it compares slum dwellers to ‘dogs’. During the process of filming, Boyle and his team of producers visited the slums and gave money to children who resided there to appear and act in certain scenes. Whilst he was lauded by many for helping those living there with his charitable donations, filming people in poverty exploits those who are already victims of oppression and renders any discussion of class, race and inequality superficial. Adoor Gopalakrishnan, a highly regarded Indian filmmaker, said that the film “underlines and endorses what the West thinks about us. It is falsehood built upon falsehood”. Slumdog Millionaire went on to win Best Picture at the 2009 Academy Awards and earned hundreds of millions at the box office, which underscores Gopalakrishnan’s point. Western audiences seem to be immediately drawn to their stereotypical and restricted view of poverty.

The movie provokes questions about the ethics of presenting poverty via film. Would visiting a slum in Mumbai or a Brazilian favela offer a profound experience that can alter your view of the world or your attitude to life? The idea that someone needs to witness poverty in another country for it to evoke empathy implies that poverty is exotic and does not exist on people’s front doors. Even before the pandemic had started, 14.5 million people were living in poverty in the UK. That equates to roughly one in every four or five. According to government data, 2688 people are sleeping rough every night. In 2020, the BBC announced it would no longer send celebrities on trips to Africa as part of Comic Relief to show the effects of war, famine or disease. This decision followed criticism of the practice as exhibiting white saviorism and resembling a new form of colonialism. Instead of giving airtime to a voyeuristic and outdated idea, their new approach is to give smaller filmmakers from diverse backgrounds an outlet to create movies reflective of their own experiences. With experience comes understanding of the subject matter, and most importantly a genuine empathy as opposed to sympathy.

With filmmaking as a form of art, is it in fact necessary to highlight the natural beauty within the mundane or even the ugly? All art perpetuates some kind of romanticisation of its subjects, merely through the artistic choice to capture them via their work. Story-makers have been presenting snapshots of people’s lives for centuries. As early as the 19th century, Charles Dickens, being a better-off individual himself, wrote about people living in terrible conditions, thus creating an interesting story for his middle-class readers. Whilst he may have acted with good intentions for a societal change, he still profited from a form of ‘poverty porn’. Filmmakers like to capture the exploited and impoverished, which could be interpreted as a form of virtue signalling. From a less cynical point of view, this may reflect the escapist desires of not only the producers but also the audience, who want to experience a form of life very different from theirs, be it in terms of class, location or the experience of ethnicities.

Featured Image Source: Slant Magazine; Still from Slumdog Millionaire