JEAN WATT reviews Michael Clark: Cosmic Dancer at the Barbican and contemplates the emotive potential of physicality.

I had never heard of Michael Clark until last week. Currently on show at the Barbican is the first major exhibition dedicated to the work of the dancer and choreographer. It is a poem to his extraordinary talent.

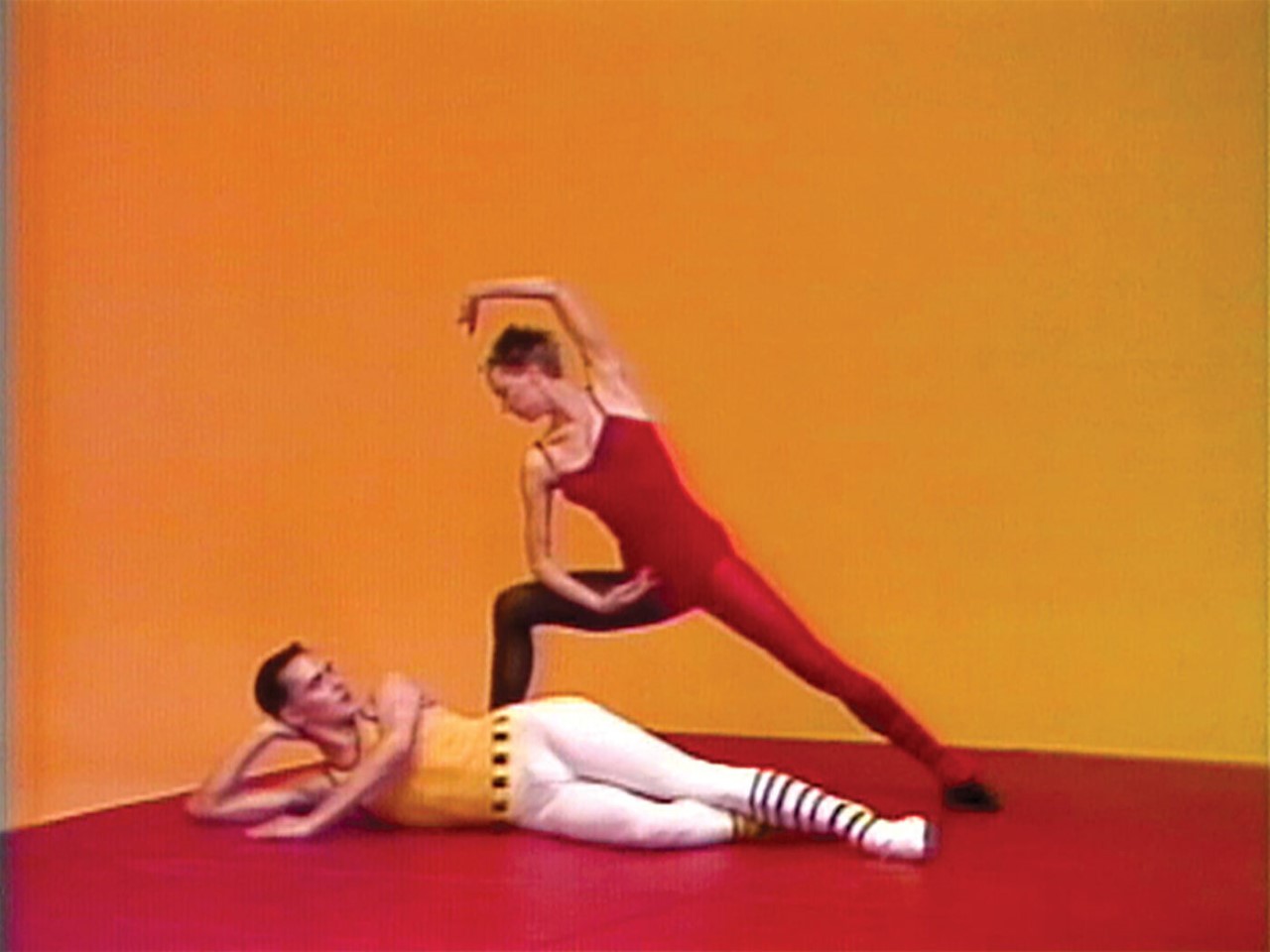

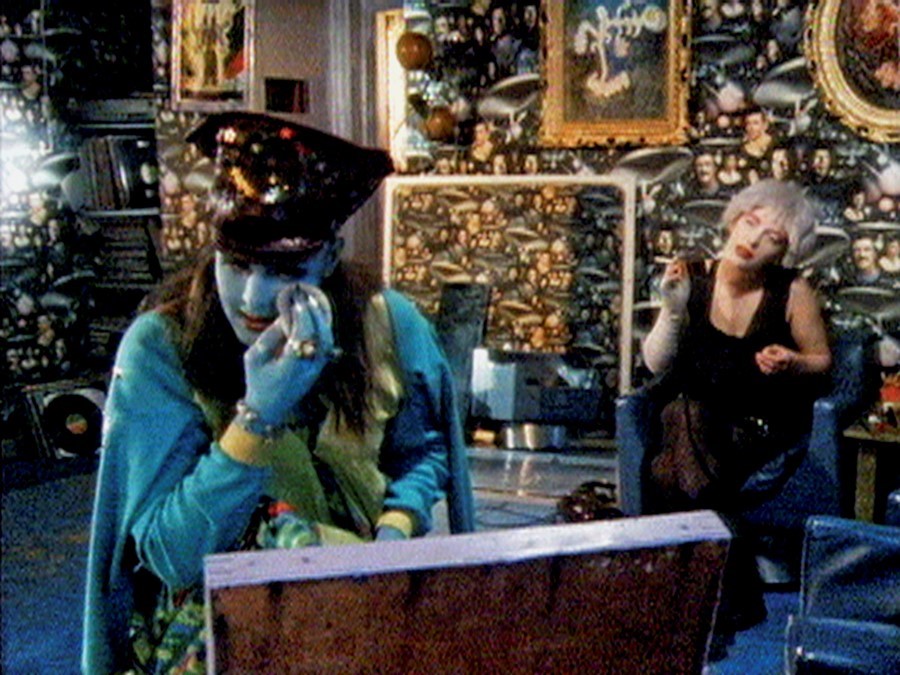

The first half of the exhibition pays homage to the long-term collaboration between Clark and filmmaker Charles Atlas. Atlas has produced a multi-screen video installation, made up of re-edited footage from two films made about Clark in the 1980s. The nine screens hang at different heights, different sizes. They are double sided, with viewpoints a-plenty. Immediately you are transported into a kind of hall of mirrors. The screens flit between footage of on-stage performances, behind-the-scenes rehearsals, dressing-room gossip and clubbing. Leigh Bowery flickers into view, bitching to fellow fashion designer and club queen, Rachel Auburn as he does his make-up. Clark prances onto stage in a bottomless leotard. The room overflows with sound: Bowie, Marc Bolan, The Fall.

What is so striking about Atlas’ film is Clark’s attention to detail. He leaps between the worlds of dance, art, music and fashion, but doesn’t let anything fall short. The costumes and make-up are near perfection: spectacularly drag, gloriously kitsch and camp. Atlas describes much of his filming as ‘a love letter to London’; documenting the creative underground and queer subcultures of the London which Clark emerged from.

Yet, despite the kitschy pantomime of it all, Clark’s choreography is also immensely moving. Coming from a traditional ballet education, Clark studied at the Royal Ballet School in the 70s before joining Ballet Rambert. His formal training bleeds into his work; using classical ballet to subvert the strictures of its traditions. This is what makes his dance so emotive. The grace and virtuosity of his ballet training is palpable.

The exhibition continues upstairs with a selection of work inspired by or about Clark. Unfortunately, it is comparatively disappointing. As is often the case in the Barbican’s space, the energy and momentum does not transfer to the upper galleries. A whole room is dedicated to a frankly underwhelming Sarah Lucas concrete cast, depicting Clark’s naked body sitting on a toilet. This is followed by a banal series of paintings by Elizabeth Peyton depicting portraits of Clark alongside his ‘heroes’. The all-consuming cohesiveness of the installation downstairs only exaggerates the boxiness of the rooms upstairs, which allow little space for wandering, considering, coming back, and little dialogue between artists and objects.

There are certain moments, however, which echo the joy of Atlas’ film: a tender and careful collection of Wolfgang Tillman’s photos, a series of heady, shadowy Silke Otto-Knap paintings, a couple of Leigh Bowery’s gaudy, brocaded costumes. But the best part about the upstairs is that you can still look down. Particularly now, with one-way systems in place, I leant over the balconies with envy at the new visitors encountering the deliciousness of the screens below. Whilst the upstairs rooms sculpted Clark into a whole, showing us how other people have seen him, what it was lacking was his hand.

I do not, however, envy the task of the curator in putting on a show about a dancer. How else can the energy of performance be conveyed apart from actually watching it unfold, whether that be live, or on video? Yet, what to do with the plentiful resources of other material about Clark? Personally, I would have cut them out, and had the whole exhibition as Atlas’ video installation, which carried enough weight on its own. But I admire the perseverance of curator Florence Ostende, who has written in the past about, ‘the whole complexity faced by venues that combine dance, performance and a museum’, like the Barbican. How to exhibit something live, after the fact? When the very nature of the work, ‘resides in the fact that the body (and not language) remains the principal vector of transmission’. Her show at the Barbican last year Into the Night: Cabarets and Clubs in Modern Art did not solve this complexity, but Clark’s show has something in it. Perhaps, it is Clark himself.

Leaving this exhibition, after hanging over the balconies to drink in the last of Atlas’ documentation of Clark, I felt invigorated. The physicality of the show, the movement of the dancers on screen, the strength of their bodies, is joyous. Particularly at the moment, whilst I feel hyper-aware of the health condition of my body, I also feel increasingly less and less bodily. When did I last dance, or dance amongst others? I travel less, I move less, I feel the limits of my body less. We are living a more remote existence – removed from ourselves. Michael Clark shocked me back into my body.

Michael Clark: Cosmic Dancer is open at the Barbican until 03.01.21

Featured image: Still of Michael Clark and Karole Armitage in Parafango, 1983–84. Still, 16mm film, duration: 38 minutes. Choreography by Karole Armitage. Courtesy of Electronic Arts Intermix, New York. Image source: BOMB Magazine.