ANNA DANG contemplates the harmful effects of mainstream heterosexual porn, and her experiences with the yaoi genre.

According to Wikipedia, yaoi is ‘a genre of media that features homoerotic relationships between male characters’. Originating in 1970s Japan, yaoi has become a worldwide phenomenon: a simple Google search leads to millions of yaoi fanfictions, comics and other artworks. And while some of the people behind this massive body of work are gay men, a staggering amount of them are straight women.

Given that the Internet offers plenty of porn featuring sex between men and women, why would so many straight women gravitate towards yaoi? As a straight woman who enjoys yaoi, the short answer is simple: we do not like watching straight porn.

Women are often accused of being prudes when we express a dislike for porn, as if we have a problem with graphic depictions of sex. But I think everyone, from the casual consumer to the hardened addict, can recognise that porn is also about power. In most videos, the man is portrayed in a dominating role, while the woman is relegated to a submissive role. She may be manhandled, insulted, and stretched into anatomically unlikely positions. ‘Relegated’ may not be the best word. The woman is usually the star in straight porn: the camera zooms in on her face, her breasts, her legs, fragmenting her body into so many targets of male desire. She is the ultimate object of sexual desire, but never the subject; the camera rarely lingers on her partner – because who would want to see that, right?

All of this highlights the fact that porn is made by men, for men. When a woman watches straight porn, it is difficult for her to ignore its representation of an unbalanced gender dynamic that is already all too obvious in everyday life. I remember going on PornHub for the first time and feeling a vague sense of shock, followed by boredom and annoyance. ‘Is this really how guys talk to girls during sex?’ I wondered. ‘Is this what I have to look and act like to be attractive to men? Why don’t I get to see more of the dude’s body?’

Looking back on it now, I think I saw yaoi as a way for me to express my interest in sex without the threat of being objectified. Straight porn had taught me that I could not be a sexually active woman and be respected at the same time – that I was allowed to experience pleasure so long as I was willing to sacrifice my autonomy, and be reduced to a merely sexual object.

In gay male erotica, this threat is erased by relegating the woman to the non-participative, but often very fun, position of third-person omniscient. Her body melts away; she becomes a voyeuristic eye, reaping the benefits of sexual and aesthetic pleasure without feeling threatened. In this blissful vanishing, she can transition from the role of sexual object to sexual subject: she is the one who desires, not the one who is desired. The male body is portrayed as desirable, beautiful, and more importantly, vulnerable – which it so rarely gets to be in mainstream straight porn.

As fun as it is, enjoying yaoi too much can have problematic consequences. Some yaoi fangirls (also known as ‘fujoshis’) end up fetishising gay male relationships in real life: I’ve witnessed women publically cooing over gay couples with no regard for their discomfort. While this behaviour doesn’t come from bad intentions, it falls in the same category as other kinds of harmful ‘positive’ stereotypes, not unlike the notion of a gay best friend to go shopping with. Moreover, many yaoi works have been criticised for romanticising things like rape and non-consensual relationships; such tropes should not be construed as a blueprint for healthy relationships, gay or otherwise.

In addition, fantasising about sexual interactions where your own gender isn’t represented can get weird when you start to become sexually active. I found myself in this awkward situation with my first boyfriend, when I realised that I was no longer used to seeing my own body as something sexual. After speaking to my girlfriends about it, I found that many of us shared similar experiences. Some of us had internalised a fear of intimacy. Others felt compelled to reproduce what they’d seen in porn. Many of us turned to yaoi as a space where we could enjoy our sexuality safely, without the fear of being judged or objectified.

I don’t regret discovering yaoi as a teenager, but I wish it hadn’t felt like the only option for me. I wish I had seen my gender represented in porn in a way that didn’t make me feel unsafe. I wish I hadn’t unconsciously believed that the only way for me to protect myself was to step off the stage.

Everyone deserves to have a safe space to explore their sexuality; a space where they don’t have to choose between pleasure and respect; a space where they see themselves represented not merely as an object of desire, but also as a subject. I say everyone, because women are not the only ones affected by the codes of porn. To say nothing about the representation of non-binary people, men also suffer from reductive representations of their gender. Most porn teaches men that they have to be domineering and brutal, and women that they have to be submissive and insatiable. But we’re all just clumsy creatures wandering in the dark, looking for intimacy, pleasure, and most of all, connection. Sex is one of the most universal ways to find that connection. As one character states in Sense8 (one of Netflix’s most sex-positive TV shows), ‘we exist because of sex. It’s not something to be afraid of: it’s something to honour, to enjoy.’ We must simply be careful about how we represent it, and the implications this can have.

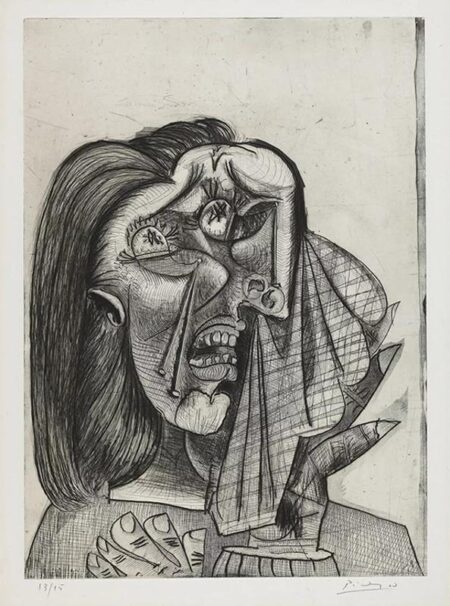

Featured image source: aminoapps.com