ENERZAYA GUNDALAI reflects on the role of technology in art through the Saatchi Gallery’s most recent exhibitions.

Nothing can escape the glare of blue light in our digital age. Blue light emanates from every computer, smartphone and television screen. Most will agree that these technologies have become inseparable from our daily existence. Contemporary art has kept pace with these developments. At the Saatchi Gallery, Georgii Uvs utilised ultraviolet (UV) light as a central component in his arwork; within a neighbouring exhibition space, the digital art studio and collective Marshmallow Laser Feast employed virtual reality (VR) headsets in their installation, We live in an Ocean of Air. Both artist and art collective manipulated light through the vehicle of technology in order to shift (and to some extent, control) the viewer’s perspective. Was it the artists’ aim in their use of artificial light to illuminate the direction of fine art in the future? In our mass production-based and image-saturated world, does technology stand contrary to art, or can the two exist symbiotically?

Donning breath and heart sensors as well as a VR headset, I stepped into the Marshmallow Laser Feast’s artificial world, We Live in an Ocean of Air. From the headset, small dots representing particles in our surrounding environment scattered as objects moved. The VR headset traced minute displacements, ripples, and vibrations in the air and revealed to me what our eyes normally cannot see. Blue dots rendered oxygen, while red dots traced the movement of carbon dioxide. I looked down and saw my barely recognisable hands. They were a mosaic of tiny red spots. When I raised my head, a colossal Sequoia tree materialised in front of me – I saw blue oxygen emanating from the tree, flowing through its roots and trunk, sustaining it. It felt as though the tree’s life force had unfolded before me. 20 minutes later, when my VR time was up, I returned my gear for the next customer to undergo the same exhilarating experience.

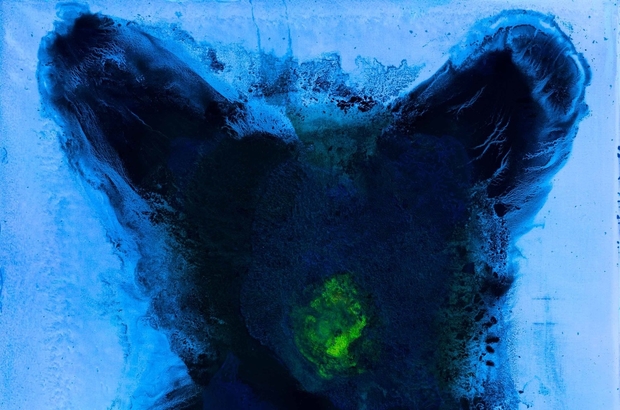

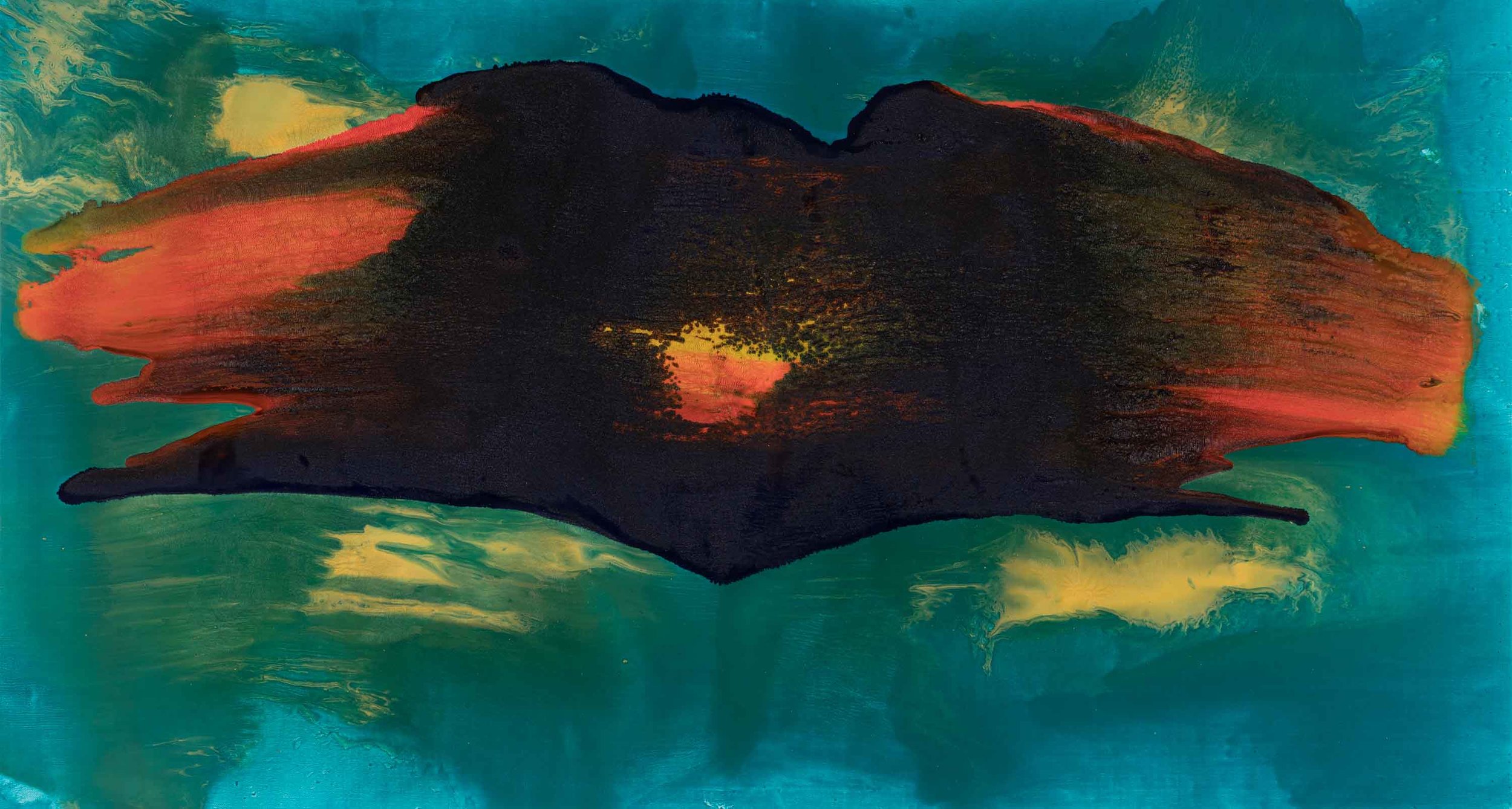

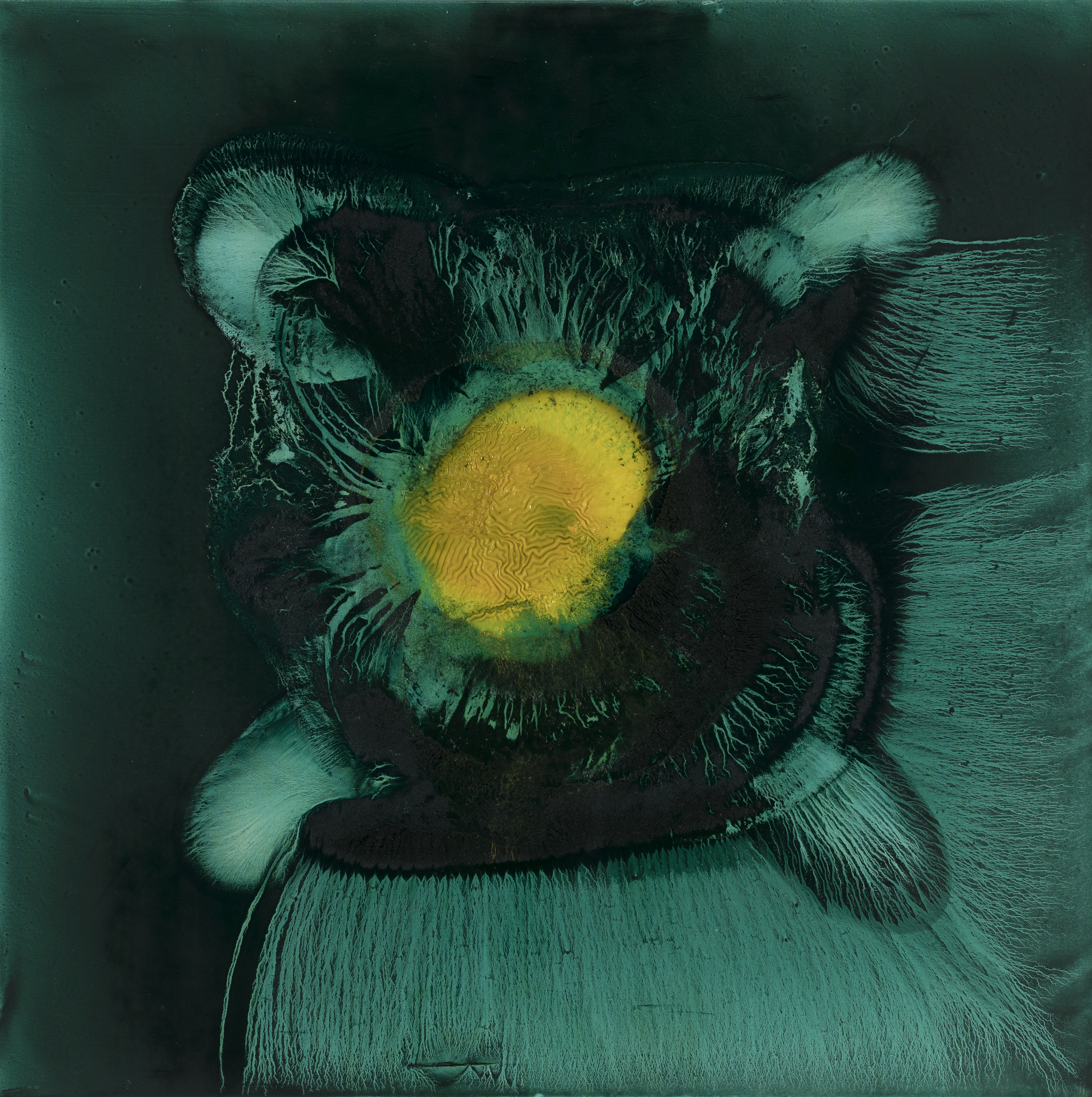

Dejected that my interaction with such a fascinating artwork was so short-lived, I decided to check out Georgii Uvs’s exhibition Full Circle: The Beauty of Inevitability on my way out. The exhibition room was spacious. Its four walls were covered with large paintings. It seemed to me that these paintings sought to capture motions in time itself. Large sweeping brushstrokes emphasised movement, juxtaposing the stillness of its own image. The ambiguity of shapes reminded me of a photograph taken on low shutter speed.

The painting’s sailing brushstrokes produced the farcical illusion that production was quick and imprecise. In reality, Uvs’ methods and materials were slow-paced and meticulous. Time was an important factor in his production processes, carefully measured to ensure that paint would dissolve and disseminate where it was intended to go. Indeed, the paintings are the result of a very lengthy process; they were made by infusing paint onto the canvas from behind. The paint was set and seeped through the porous cloth, and dried on the other end of the canvas. In some cases, this process took up to three years.

Gazing upon Wings no. 2, I discerned a pair of butterfly wings. Another piece depicted a Martian-like landscape. Uvs’s precision in his use of materials was further emphasised when the UV light was switched on. The fluorescent colours glowed. Patterns and shapes shifted and revealed themselves. The walls themselves seemed to contort, as white was the colour that glowed under this blue light the most. His works evolved before me, and as my eyes adjusted slowly to the light, I felt like I was in a hallucinogenic state.

Despite the interactive and immersive conditions of We Live in an Ocean of Air, my experience felt restrictively choreographed and controlled by someone else. My visual interaction was determined by the digital art studio. I asked myself, can’t technology exist in art without such a directive? What about my own viewership and agency? Uvs’s Full Circle: The Inevitability of Beauty, is more open to fluidity in interpretation. In fact, the UV light emitted a mystical aura upon the paintings, producing delightfully alien lands that I could project myself into. With each successive change in the lighting, the ephemerality of each passing moment became more and more apparent.

Art enhanced with artificial, blue, or ultraviolet light, paves a new road for artists. Technology may enhance our vision, allowing us to see beyond our own biological capabilities, or reveal to us another perspective in looking at things. But there are many pitfalls along the way. This path is especially treacherous for young artists: we should be careful to prevent technologies from stealing the agency of the viewer or reducing the value of the artwork and experience in our technologically saturated world. Technology also has the potential to devalue an artwork, through its ability to produce and reproduce an image. Our own experiences interacting with the world around us may also become contrived, our emotions filtered through blue-lit screens and virtual realities.

When an object has been replicated, on screen or otherwise, the copy will never stand equal to the original. Although a purpose of We Live in an Ocean of Air was to establish a ‘connection between plant and human,’ I felt the connection I found with the virtual tree undermines my connection to a real tree.

The effect of mechanical reproduction is most acutely felt when objects are produced on a mass scale. This is why fine art produced in singular instances has been a ‘high’ cultural form, whereas advertisements and posters are comparatively ‘low’ forms, as argued by cultural critic and essayist Walter Benjamin. My experience of We Live in an Ocean of Air was degraded by its commercial viability, my interaction with the artwork defined within a strict, 20-minute timeframe. It seems art stands diametrically opposed to technology. Art possesses authenticity, a presence in time and space – a cultural context. It may also have the additional qualities of creativity, genius, eternal value and mystery. The literary theorist and essayist Viktor Shlovsky says the purpose of art is:

‘That one may recover the sensation of life; it exists to make one feel things… to make the object ‘unfamiliar,’ to make forms difficult, to increase the difficulty and length of perception because the process of perception is an aesthetic end in itself and must be prolonged.’

While technology makes objects convenient to view, its abuse and overuse render art objects lofty and indigestible. It’s a fine balance merging technology and art without stripping the cultural value of an artwork.

Marshmallow Laser Feast’s We Live in an Ocean of Air is on view now at Saatchi Gallery in London until May 1st, 2019. Georgii Uvs’ Full Circle: The Beauty of Inevitability was on view from January 24th to February 22nd, 2019.

Featured image: Georgii Uvs, Genesis no. 3 [UV Light Exposure], 2017. Image credit: Georgii Uvs.