WILL FERREIRA DYKE contemplates Frida Kahlo’s place in art history and her associations with modern feminism.

Known for her iconic monobrow and exuberant self-portraits, Frida Kahlo (1907- 1954) has become synonymous with activism and feminist theory. She is a figure whom I exceeding adore. I sit here writing this article in a room complete with a framed print of the artistic genius herself looking down upon me, which I dutifully purchased after attending the V&A’s 2018 exhibition Frida Kahlo: Making Herself Up. Her elevated presence in my living space is seemingly Christ-like, so it must be apparent that such a purchase was rooted in feelings of love and admiration.

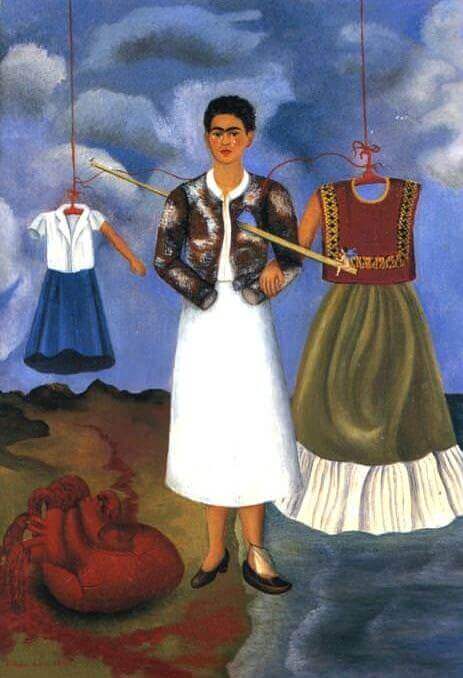

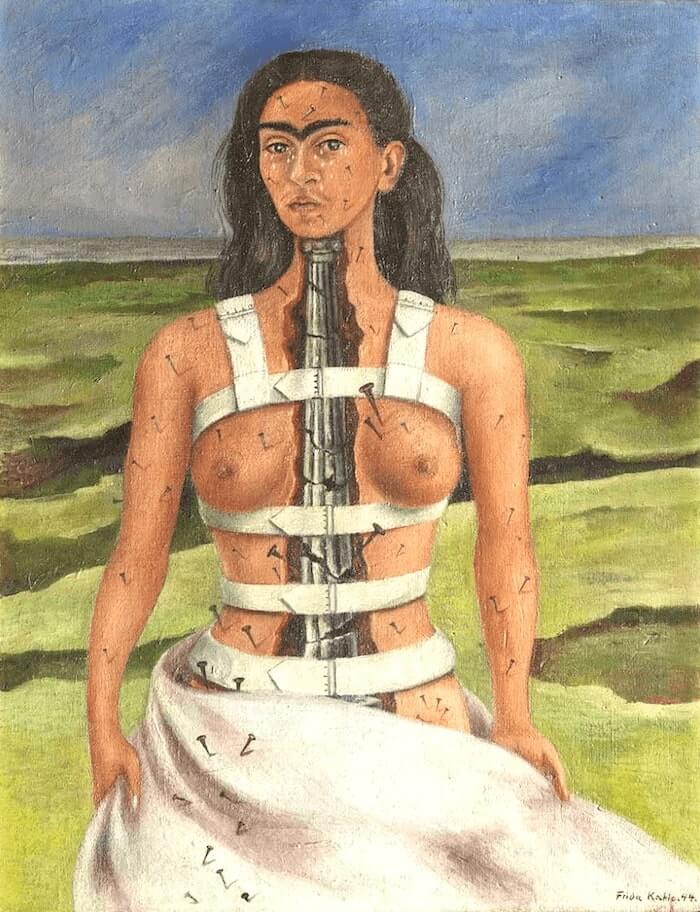

I first would like to outline some of my favourite works of hers; The Two Frida’s (1939), The Broken Column (1944) and Memory, the Heart (1937). These are deeply emotive explorations of the self and of personal experiences. From depicting her life altering injury and the repercussions of the spinal surgery she underwent at the age of eighteen, to illustrating the deepest anguish resulting from her husband Diego Rivera’s affair with her sister Christina. Memory, The Heart (1937) shows Kahlo’s impassive face filled with tears rested on an armless body; such physical wounds demonstrate her psychological helplessness post-divorce. The piece is a confluence of themes, ranging from identity to resentment, which work to deliver a succinct message of heartbreak – this message further reinforced by the prodigious weeping heart in the background. Much of Kahlo’s work produces a compelling visual narrative, filled with idiosyncratic vehemence.

My problem with Kahlo, however, is not an issue with her or her artistic capabilities. Rather, the trouble stems from how her success is often used as a reference point discussions of the longevity of women in art, and as an argument against the patriarchal lineage of the discipline. Kahlo’s fame is often used to counter feminist critiques of the lacking presence and appreciation of women in art history. Art Historian Linda Nochlin in her famous essay Why Have there Been No Great Female Artists argues this to be one of the first responses people have against this question, conjuring up worthy examples of female artists as a rationale to disprove the belief that there are none within the canon. Nochlin continues by saying how such responses do nothing to break down the western patriarchal discipline of art, but rather tactically cover up such anxieties. Kahlo cannot and should not represent all female artists. Such homogenisation is problematic, for it assumes a singular female experience and aesthetic unity, which completely violates female individualism, an accreditation which is bestowed upon male artists inherently.

One is constantly bombarded with Frida imagery, whether that be in market stalls in Camden Town or on every Etsy site, resulting in a commercialised Kahlo. This monetised figure is detached from the artist’s own achievements and has become a symbol of ‘woke-ness’. I don’t wholeheartedly hate this; such immense celebration of a non-white female figure in the western world is refreshing to see. Yet her overt symbolism has stripped this surrealist of any authentic complexity of self. She is not seen as an individual, but rather as a visual stamp, suggestive of political liberalism.

Kahlo’s merchandise is just one example of how activism can be purely performative. Fast fashion companies such as Zara have used Kahlo’s image on t-shirts. I find this feminist paradox exceptionally difficult to reason with. These companies function via racially discriminative practices inherent to their business model in order to maximise profit, whilst on a surface level they proclaim their celebration of minority figures. Here it must also be said that the appropriation of feminist slogans is not restricted to fast fashion companies, but high fashion houses also. Maria Grazia Chiuri, creative director at Dior, has been criticised numerous times for her disingenuous attempts to capitalise on feminism. In her 2016 Paris Fashion Week show, a model walked down the runway in a white t-shirt branded ‘We Should All Be Feminists’ as a nod to Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s text. This particular item cost $750: a far cry from the inclusive feminism it boasted.

Though I still feel an affection towards the saintly painter, I cannot help but fear Kahlo’s iconography is now tinged with a feminist falsehood. I shall not be removing the print from my wall, nor shall I despise a birthday card I once received which says, ‘Feel Frida Party’. But having this knowledge and awareness of Kahlo’s appropriation is necessary to allow for female artists to be understood independently. It allows for a progression towards a feminist reform, not against one.

Featured image source: smithsonianmag.com.