ALASTAIR CURTIS reviews ‘Painters’ Paintings: From Freud to Van Dyck’ at The National Gallery.

It’s often said that our belongings make up who we are. Books, coffee stains, unpaid bills and an assembly of empties — alarmingly, my desk says a good deal about me at the moment: a near penniless English Literature student faltering through a stuffy London summer. But this is also the premise of the National Gallery’s new exhibition, which looks at the acquisitions — many famous, some less well-known but not without merit — that adorned the walls and work-surfaces of art history’s most prolific artist-cum-collectors. The exhibition traverses five hundred years, intriguingly arranged in reverse chronological order and displaying the private collections that once ignited the imagination of artists as various as Freud, Matisse, Degas, Leighton, Watts, Lawrence, Reynolds and Van Dyck.

It is a cliche that ‘nothing comes from nothing’, or that an artist’s output is a coming together of elements taken from work they might have previously seen or bought. A compulsive collector, Edgar Degas accrued countless works from neoclassical artists like Corot and Delacroix, but also from his Impressionist contemporaries, eventually buying himself out of house and home. Degas’ profligacy supported the growth of Impressionism in its earliest stages, funding the experimentation of its major exponents like Cezanne and Gauguin. It was also Degas who partially restored Edouard Manet’s ‘The Execution of Maximilian’, with its portrayal of brusque brutality against a throbbing, leaden sky. Spliced into fragments after Manet’s death, Degas painstakingly tracked down four of its fragments with a ruthless, no-expenses-spared determination and mounted them on a single canvas to create what is a fragmentary masterpiece.

But this exhibition goes on to suggest that Degas’ collection was fundamental to the production of his art, keenly influencing his interests and developing technique. Sources of inspiration were rich and multifarious. ‘Bather with Outstretched Arms’, Cezanne’s portrait of a hulking semi-naked youth, standing cocksure before a crisp lake, began Degas’ enduring interest in nudes. By displaying Degas’ works alongside those from his collection, the exhibition succeeds in drawing speculative but compelling comparisons. Nearby, for instance, the nude men and women in Degas’ ‘Young Spartans Exercising’ exhibit a similar brazen sexuality on a scorched and fabulously orange wasteland. Georges Jeanniot’s ‘Conscripts’, only recently rediscovered, struggles to hold its own against Degas’ nudes, but the frigid vulnerability of the naked men, suddenly marshalled into action, is frighteningly evocative. It’s an obscure work, but also a reminder that Degas couldn’t afford to be snobbish when hunting for inspiration.

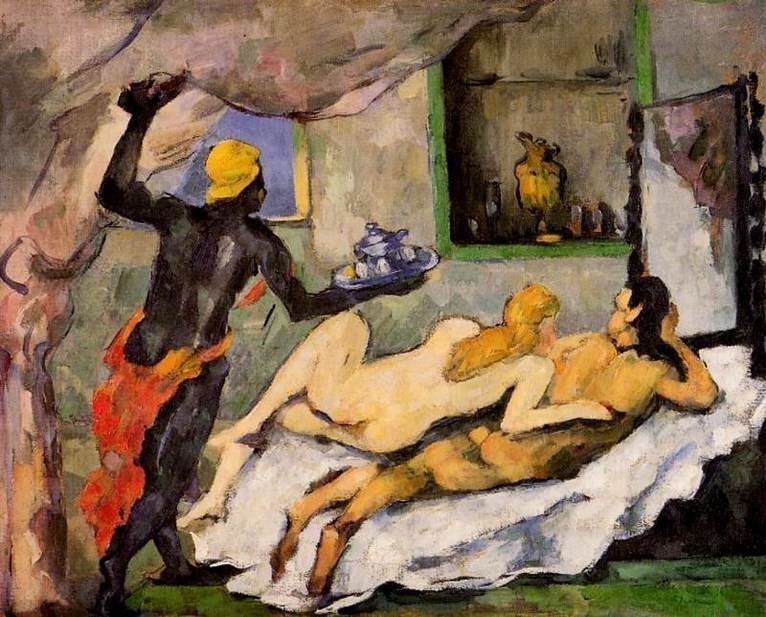

Over the exhibition’s six rooms, it is Cezanne who most frequently inspires artists’ devotion. Matisse handed over his wife’s dowry for Cezanne’s ‘Three Bathers’, an ungainly nude of three women swathed in an intensely violet light. Cezanne’s brothel scene in ‘Afternoon in Naples’, with its two gauche lovers, a tangle of distended limbs threaded between cool white sheets, was described by the late Lucien Freud as ‘erotic and funny’ and became a revered addition to his studio wall. Its peculiar eroticism inspires Freud’s own works, most obviously ‘After Cezanne’, a modern, disaffected riposte to ‘Afternoon in Naples’, but also the unclothed and uncanny intimacy of ‘After Breakfast’. It is the artist’s equivalent to six degrees of separation: Matisse liked Degas, Degas liked Cezanne, Cezanne was liked by Freud. Through thoughtful curation, the exhibition makes tangible these unspoken conversations taking place between artists often centuries apart.

Corot’s Italian Woman was the inspiration behind the exhibition. A portrait of a noblewoman in the Renaissance style, within its trenchant colours and vivid realism one can find the seeds of the work of Picasso, Freud and countless future artistic movements. Corot, though, is best known as a landscape painter and several of his works appear in Lord Leighton’s collection. In ‘The Four Times of Day’, a breathtaking series of decorative panels, Corot captures a landscape as it transitions from dawn to dusk. Dressed in electric red coats and bright blue caps, labourers toil under a canopy of birches during the day; later, the sweltering sun is replaced by a livid sunset, to be pacified still later by a cool, complete darkness, imbuing the workers —now boating on the lake— with all the mystery of forest spirits. It is a good metaphor for the exhibition: artistic movements grow and wane like the day, but it is all part of a larger and timeless continuum.

After this, the collections of Victorian artists Watts and Thomas Lawrence do seem disappointing, partly because the material is so disparate — Rembrandt sketches, a Bellini, Jacapo Bassano’s quietly profound ‘The Good Samaritan’ — all singularly brilliant, but lacking the throughline that made the earlier Impressionist and Post-Impressionist rooms so enthralling. The work of these artists also fails to captivate, particularly that of Joshua Reynolds. His work, though not without shimmers of brilliance, never amounts to the grandeur of the Old Masters he tries to emulate. There’s something quietly tragic about his ‘Self-Portrait’. Burly and proud, his hand resting on a badly-lit bust of Michelangelo, it might suggest he is a natural successor to the Old Masters; Reynolds’ works, displayed alongside, argue to the contrary that he is a man destined to live in the shadow of his great collection. Possessing good art does not always make one a good artist.

The same cannot be said for Van Dyck, whose collection and works end the exhibition. Van Dyck spent his artistic career translating Titian’s genius into his own hand and his work recycles the same dazzling light effects and dynamic framing, but reinterpreted for a new context. Titian’s ‘Portrait of Gerolamo Barbringo’ — Barbringo’s back turned, head fixed in a sideways glance and his gaze searching for the viewer — finds its descendent in Van Dyck’s double portrait of ‘Thomas Killigrew and William Crofts’. Killigrew exhibits the same piercing gaze but here it’s not a warm, inviting gesture; instead, despondent and distracted, his wife recently having died, he looks to us to salve his pain.

T S Eliot once wrote of the ‘simultaneity of past and present’: again and again, artists rake their inspiration from the art of their predecessors, creating a conversation that echoes down the ages, culminating — finally and unbearably — with us, the viewers. Simply unmissable.

‘Painters’ Paintings: From Freud to Van Dyck’ runs at The National Gallery until 4th September.