EMMA GABOR discusses the work of eighteenth-century painter Carl Spitzweg, linking the emergence of the Biedermeier period in Germany to the burgeoning of his artistic career.

A self-taught artist who originally trained as a pharmacist, Carl Spitzweg only took his artistic practice up as a full-time endeavour in 1833 at the age of twenty-five, after coming into some independence-providing inheritance. Before this advantage, Spitzweg was an illustrator for a satirical magazine. His humorous works are representative of the Biedermeier style, which emerged around the time of the Metternich government in Germany. This period was focused on settling down, doing ‘unhistorical things’, and living a regular, everyday life; a reaction to the turbulence of the Napoleonic Wars that preceded it.

However charmingly Spitzweg represented the everyday norm, his paintings filled with jokes and smiles, his works also contain a silently observing satirical master behind his magic brush. Spitzweg’s style was inherently German and yet, a great deal of him was a clown, appealing to all men. This knowing playfulness, however gentle, is what gave him his essence. It made him not so much German or European as it made him universal. His humour has a worldly satire that surely appeals to the humour of all. This goes hand in hand with the Biedermeier style, which grew out of Germany’s post-war economic impoverishment to become that of the rising middle-class. Its vital elements were a cultural interest in literature, poetry, and dancing.

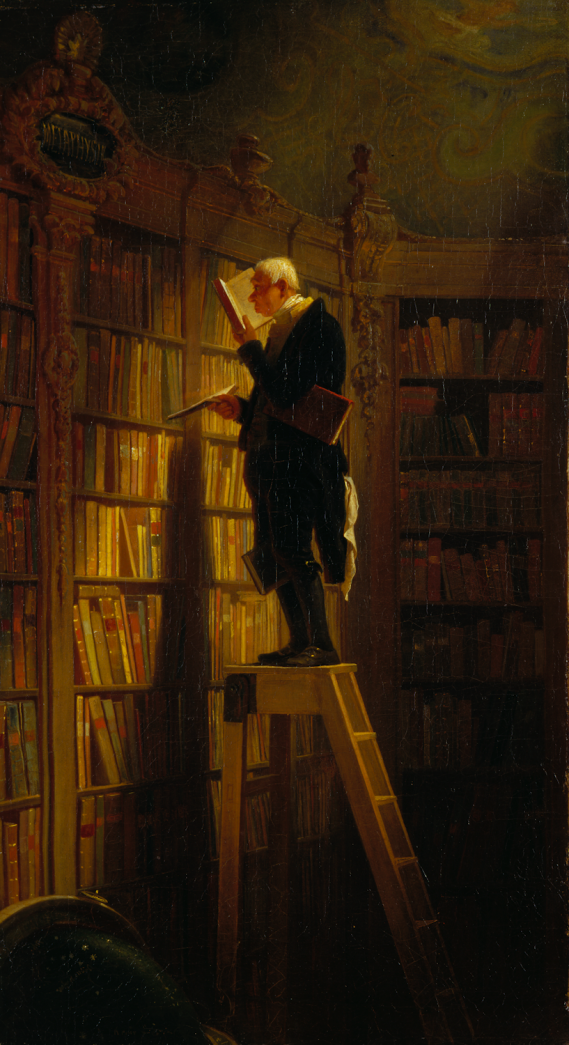

These were elements incited by the infamous soirées of the middle-class, the prevalence of such social gatherings creating an intellectual peer pressure to be more learned and cultured than your neighbour. It was such a mentality that inspired works such as Spitzweg’s The Bookworm (c.1850), arguably the artist’s most famous painting. This particular work portrays an eccentric male figure standing on a ladder in a library, low enough that his position is not dangerous, yet high enough to suggest a desire to escape into another world. This world is that of metaphysics, as detailed in the inscription in the top left of the image, above the many bookshelves; this man is attempting to gain knowledge of this science through the literature he reads. He is lost in another universe, holding books in his hands, under his arms and between his legs, and yet he is strangely present. Surrounded by bookshelves upon bookshelves, the figure is lit by the sunlight coming from the ceiling, the space appearing dated and old yet welcoming this stranger into its secrets.

If this is to be considered a satirical image, as I believe it wickedly must be, then the subtle, implicit nature of the satire adds to the humorousness and makes it evermore delightful. While satire’s nature is equally true and untrue at the same time, it rather often conveys a sense of maliciousness or hostility towards the figures being ridiculed. However, here, there is an innocent satire implicated, one that leaves the spectator smiling, rather than feeling an uncomfortable guilt.

Spitzweg ridicules the Bookworm for his rushed desire to know everything at once, as though he were expecting to read multiple books at the same time. The figure, while absorbed in his activity, appears out of place, as though recently having been acquainted with the world of metaphysics. In short, he is trying too hard, an act that portrays him as desperate, which may be easily imagined considering his status as a rising bourgeois of the 19th century: with less focus on politics and more on domestic life, intellect became of principal importance – indeed, the pressure was on. Equally so, if this is a member of the middle class attempting to imitate the upper classes by trying to look highly educated, then it is no wonder Spitzweg took it upon himself to ridicule such an individual; he did so, even when there was far less reason to caricature someone (see, for example, The Poor Poet, 1839). It is also important to note that Spitzweg typically did not portray particular individuals; rather, he was painting a generalised image of a typical rising bourgeois desperate for the quick acquisition of intellect.

The origins of the Biedermeier style coincide with the origins of Spitzweg’s works and the development of his painterly, creative self. Undeniably, both the Biedermeier and Spitzweg remain universal, having found their origins mutually; the Biedermeier’s artefacts are still immensely popular today and Spitzweg’s oeuvres contain humorous subjects that may be contextualized anywhere and anytime. Therefore, while Spitzweg’s essence is inextricably embedded within the culture of the Biedermeier, the little satirical success of the Biedermeier should certainly be credited to Spitzweg’s mastery.

Featured image: Carl Spitzweg, The Widower, 1844. Oil on canvas. 58 x 66.5 cm. Städel Museum, Germany. Image courtesy of Städel Museum.