DANIEL LUBIN reviews The Swarm at the VAULT Festival.

The Swarm opens by confronting the British crowd with its deepest darkest fear: audience participation. Whilst the actors lie in a huddle on the dusty floor of a darkened tunnel at The Vaults, a recorded voice in a strangely distorted melody commands the theatregoers to hum to ‘activate’ the bees. After a silence, some test the water with tentative grumbles before backing down into silent embarrassment. We were invited to form a collective, to unite through music of the most basic kind, but we couldn’t bring ourselves to. The bees went on to show us exactly how it’s done.

The show is wonderfully obscure and creative, a bizarre and mesmerising combination of physical theatre, dance, recorded soundscape and live operatic performance, which applauds the mechanisms of nature. The idea can be framed as an artistic representation of a very scientific study into the unseen art of bees. That is, the bees’ behaviour is ordered into distinct phases, which are then translated onto the human stage through such abstract performance. The pamphlet handed out on entrance provided a phase-by-phase guide through the elusive narrative that detailed these beautiful complexities of activity; even the chemical diagram of the bees’ communicative hormone, pheromone, was printed.

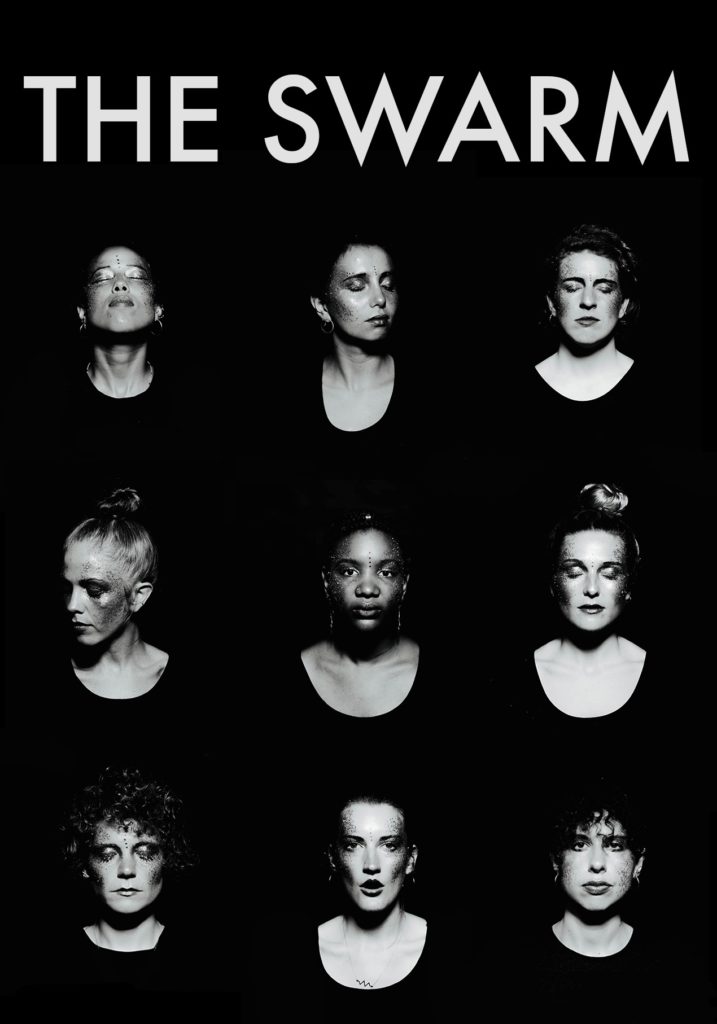

Such a celebration of bees defies all possible preconceptions – all things typically bee-like are removed: the costumes are varying shades of brown and maroon rather than a garish yellow; rather than black stripes the actors’ faces are painted with silver spots. The dull threatening buzz you hear in summer is replaced by eerie harmonies. And harmony is just the word, because once these superficial components of bees are removed, the community and coordination is what’s left of bee ‘culture’. Our impression of bees is utterly transformed once we are presented with something so alien. The otherworldly awakening of the bees whilst bathed in a warm orange glow from floor-level lighting had an unavoidably mystical air. With such absolute synchronicity in movement as in musical expression, the nine-piece choir of bees manifested itself as a single entity: a swarm.

The female cast of nine actors coordinated perfectly to form the collective they were. Starting initially on the floor with eyes shut, their hands gradually edged towards each other to feel how the group was moving. Conducted by the eerie recorded drumbeat they constantly sang to, they were able to so subtly develop their motions that it was difficult to notice an overall process even happening: suddenly the group would have formed a circle, next they’d have risen from the stone floor. Through this meticulous choreography, it felt as though the individual bees were themselves moving randomly, spontaneously, but towards a general progression.

Yet this collective was ultimately, subtly made of individuals. Each actor had her own unique movement in the scene where the bees were (according to the guide) looking for a location for the new hive; and each bee was given idiosyncratic characteristics. In one of the last phases the bees stood in a circle and the audience was encouraged to observe how they looked at each other, with expressions of focus or excitement and the odd smile. Nine actors bending their knees to a beat in their own individual ways characterises them as nine individuals. These minute idiosyncrasies were only noticeable in contrast to the otherwise general uniformity of costume, movement and indeed sex – perhaps a mixed-sex cast would not have had the same unity as this all female troupe did. Though the play contained no dialogue, by the end of the hour each bee felt distinctly characterised, and in a way re-humanised.

The guide detailed how much inspiration was taken from indigenous tribes and other micro-cultures from across the globe: the silver spots on the bees faces were inspired by the Ethiopian Karo tribe; polyphonic singing techniques were inspired by the Baka people of the Congo and Cameroon; ‘interlocking meldoies’ were based on Zimbabwean Mbira music. Structured around these unfamiliar yet hugely evocative musical concepts, Heloise Tunstall-Behrens (artistic director, composer and producer) wrote lyrics in one scene to show the bees communicating the potential new homes they’ve found: ‘Shi-ny, shi-ny, tem-per-ate’, ‘Hollow tree, hollow tree, yeah, yeah, gar-den, not far away’. Though in English, when broken up into syllables and chanted with such unfamiliar melodies, the language becomes alien and obscure – the message is carried more through the physicality and music than the words. This cultural amalgamation exposes us to other types of aesthetic, and in doing so elevates the status of bees, likening their community with all its rituals and complexities to a human culture. In drawing on the unacknowledged beauty of other cultures, The Swarm comments on the overlooked beauty of nature.

The audience’s negative reaction to such an invitation to hum could surely not have been predicted, yet it provided the perfect contrast to the performance. We fear each other and each other’s judgement; we couldn’t even draw together for the shortest of moments to make the basest of sounds. The bees build off each other, reliant on their peers’ direction through touch while they were shut-eyed; as a result they could rise as on. The Swarm is an amazing insight into a community taken for granted, one of astounding and totally organic scientific mechanism, and one that humans could learn from.

The Swarm played from 8th-12th Feb at the VAULT Festival (Jan 25th – Mar 5th 2017). Find more information here.

Featured image courtesy of