SAYEH YOUSEFI reviews an event at the British Library delving into Sylvia Plath’s personal letters and the light they shed on her as a writer.

Decades after her untimely death, the life and works of Sylvia Plath are regarded as one of the pinnacles of literary curiosity. One of the most acclaimed poets of her generation and a pioneer for women writers, Plath’s personal life is often overshadowed by her grave, her public reputation and her, at times, tragic work. In an effort to gain a greater understanding into the life and thoughts of Plath, editors Karen V. Kukil and Peter K. Steinburg have curated The Letters of Sylvia Plath Volume II: 1956–1963. Published by Faber and Faber, this new volume consists of a collection of letters from the later years of Plath’s life, providing readers and scholars insight into her work and personal life. They give a new look into her relationship with her husband Ted Hughes, particularly after his affair, and most importantly, demonstrate Plath’s commitment to her life and work despite her depression. They also lay out a contextual framework that brilliantly complements her writing, often inspired by her everyday experiences. A panel discussion hosted by the British Library entitled Triple-Threat Woman: The Letters of Sylvia Plath celebrated the launch of this volume. The editors were joined by two leading Plath scholars, Heather Clark and Mark Ford, who shared their understanding of the letters and their personal responses to the life and work of Plath.

Karen Kukil, one of the co-editors of the book and leader in the project, selected several excerpts from Plath’s letters that provided an introspective insight into some of the most formative moments of her life. One letter to her good friend and college roommate, Marcia B. Stern, relates the account of her first meeting with Ted Hughes. She speaks of him as ‘the only man I’ve ever met who I can’t boss’ and praised his writing abilities. Plath would go on to help launch Hughes’ career in the U.S., while he too encouraged her to commit her time to writing and pursuing poetry wholeheartedly. Plath was committed to Hughes both in their marriage and in their careers; she respected him as a poet as much as she did a spouse, and saw him as a complement to herself.

The letters also include her correspondences with her psychiatrist Ruth Tiffany Barnhouse, whom Plath reached out to after learning of her husband’s infidelity. Plath was very open with Ruth, and wrote to her for advice during and after her separation from Hughes. In spite of the heartbreak that ensued after Plath’s discovery of her husband’s affair, she retains a certain degree of optimism, as her letters suggest. She would have liked to remain friends with Hughes and thought the poems to his mistress were poetically admirable. As Heather Clark aptly observed, Plath’s composure and gallant respect for Hughes’ poetry even immediately after learning of his affair speak highly of her character.

The title of the volumes, and the evening itself, is a reference to a letter dated the 9th of April 1957, in which Plath had written to Stern, saying, ‘If I want to keep on being a triple–threat woman: writer, wife and teacher… I can’t be a drudge.’ Plath was well aware of the difficulties of being an ambitious woman, let alone an ambitious woman writer, in her time. She was still committed to living her ‘own life’, as she said herself in a letter in 1962, and was proactive in trying to find a network of women with similar goals and ambitions.

Heather Clark made a striking point when asked about the importance of these letters to the general public’s understanding of Plath and her work: the letters demonstrate that even in the weeks that preceded suicide, Plath was committed to living a full life. She was trying to cultivate a network of women writers, partly to aid her literary career, but also as a source of inspiration for the fulfilling life she desired to lead, regardless of the betrayal of her then-separated husband. Despite the common perception of Plath as a solely emotionally-fuelled figure, she was not utterly and irreparably devastated by her husband’s infidelity, but was committed to living on, and living fully, in spite of everything he had done.

In this regard, the letters help shatter the many misconceptions around Plath as an eternally depressed writer with no interest or commitment to life. They show that in spite of her struggle with depression, the stigma of raising her children as a single mother, and all the while trying to carry forward her literary career in a patriarchal structure, Plath was incredibly resilient and committed to perseverance.

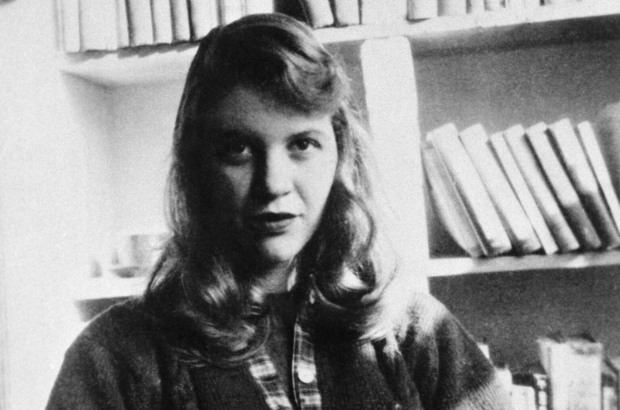

Featured image source: www.poetryfoundation.org