BEA BOWLES-BRAY uncovers the origins and legacy of playwright Harold Pinter.

You would struggle to find anybody better suited to play the voice of Harold Pinter than Kenneth Cranham. Cranham starred alongside the playwright in the acclaimed BBC adaptation of The Birthday Party in 1987, and has trod the boards for many of Pinter’s finest productions, including The Dumb Waiter, The Homecoming and The Caretaker. Speaking to Cranham at Jewish Book Week cultural festival, the actor recalls dining with the playwright in the last months of his life, and the zeal with which they fired lines of Shakespeare at each other.

Reciting passages of Pinter’s early prose to a packed audience at King’s Place, Cranham reveals a fascination with Renaissance theatre that is not often discussed in relation to Pinter. The playwright’s first exposure to drama was playing Macbeth as a teenager at Hackney Downs School. His earliest employment was touring Ireland, acting Horatio (Hamlet), Bassanio (The Merchant of Venice) and Cassio (Othello) for the glamorous wage of six pounds a week and discounted cigarettes. But how did this immersion in Shakespeare shape Pinter as a playwright? In 1765, the writer Samuel Johnson claimed that Shakespeare ‘exhibited the real state of sublunary nature’, in which ‘the loss of one is the gain of another; and many mischiefs and many benefits are done and hindered without design’. In a God-fearing age, the amoral inclusivity and absence of divine ‘design’ Johnson found in Shakespeare’s oeuvre was incredibly alarming. In more scatological terms – as was his custom – Pinter asserts the virtues of this quality:

‘In attempting to approach Shakespeare’s work in its entirety, you are called upon to grapple with a perspective in which the horizon alternately collapses and reforms behind you. All are contained in the wound which Shakespeare does not attempt to sew up or reshape, whose pain he does not attempt to eradicate. He turns and bites his own tail. He defecates on his own carpet.’

This final image from his 1951 essay, ‘A Note on Shakespeare’, reappears in one of Pinter’s final plays, One for the Road (1984), where the torturer remarks,

‘you know what it’s like – they have such responsibilities – and they feel them – they are constantly present – day and night – their responsibilities – and so, sometimes, they piss on a few rugs.’

This echo, which spans the breadth of the playwright’s career, is emblematic of a permeated influence of Shakespeare throughout, which we find in Pinter’s preoccupation with those at the margins of society, and in the undercurrent of chaos which pervades his oeuvre. As an inheritor of modernist and absurdist traditions, Pinter is typically associated with Samuel Beckett and James Joyce. Yet as Cranham narrates Pinter’s prose, it becomes clear that it was Shakespeare and Webster, not the modernists, who first inspired him. Indeed, Pinter recounts his father demanding that Ulysses be removed from the mantelpiece, as ‘he wouldn’t have that book in the same room where my mother served supper’.

Devised by Tristram Powell, who directed Foyle’s War, and produced Shades: Three Plays by Samuel Beckett, the event at JBW interspersed passages of prose with sections of Pinter’s early sketches. The material situated Pinter as a thoroughly London writer – from his fascination with the city’s bus routes in Request Stop, to his loving portrayal of Evening Standard distributors in Last To Go. Starkly contrasting the location-less settings of a Beckettian drama, Pinter’s characters are en route to Shepherd’s Bush, killing time at Embankment, or famously striving, like Davies in The Caretaker, to reach the unreachable Sidcup. ‘Voices from Pinterland’ highlighted how the city becomes a presence akin to a character in the works of Harold Pinter.

As the event draws to a close, I feel I have learnt much about the often-overlooked persona of Pinter the East End local; the teenager so proud of his Macbeth costume that he kept it on for the duration of his journey home on the 38 bus. Walking out of the auditorium, I realise I am stood beside Antonia Fraser, the celebrated author and Pinter’s widow. It strikes me that I have attended an event curated with great care by those who love not only Harold Pinter the writer, but Harold Pinter the human being. In the Q&A which followed, renowned theatre critic Michael Billington said that Pinter appreciated actors. At a time when players were often denigrated as ‘luvvies’, Pinter encouraged and supported the acting talent around him. ‘Voices from Pinterland’ demonstrates the legacy of this support and encouragement.

‘Voices from Pinterland’ on 5th March was part of Jewish Book Week cultural festival. For more information about the festival, visit http://jewishbookweek.com.

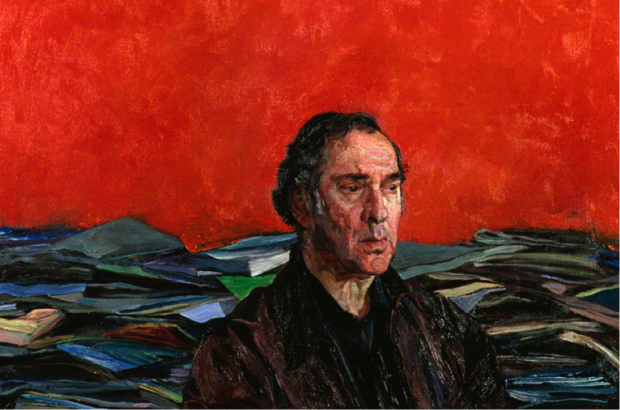

Featured image courtesy of Justin Mortimer.