Building affinity among diasporic communities in the U.K.

A piece by HARVI CHERA.

There’s a difference between the following two questions:

- Where you from?

- Where are you from?

The second indicates a friendly curiosity at best. However, those who make up Britain’s diasporic communities are all too familiar with the exoticism or worse, the divisiveness and feeling of hostile otherness, this question can create. Put simply, with recognition of the speaker’s intention, there are far more sensitive and common-sense ways to ask someone’s ethnicity (and more likely than not, if they like you they will indulge your interest without the need to ask). But that’s not what this article is about.

I am far more interested in the first question, and how at the local barber’s or falafel place the first-generation immigrant in their mid-50s asks ‘where you from?’ – harsh, explosive, without regard for any verbal omissions.

I sit, relaxed, in the barber’s chair after being asked it this time. The stifled sound of aeroplanes whooshing past comes from the ’90s black box TV in the corner of the room. A Turkish news channel is playing at almost mute volume in the background. A thought ticks in my head and I’m reminded of my dad who routinely lowers the volume to a barely audible murmur when he watches gameshows on the TV – if anyone else is in the room they immediately complain that they can hardly hear the programme. But it’s clear. He has a different point of view of how best to watch. He enjoys the tranquil hum of the TV and quiet company of anyone sitting with him. At this volume you can sit and chat without being in a shouting contest with the TV.

Similarly, the Turkish barber has a different point of view and purpose in asking his BAME* customer’s roots. The blunt tone he uses, that of a non-native English speaker, is forgivable. In mixed company this question, particularly its directness, would create shock, but in the territory of the POC-owned** business, it builds affinity between BAME worker and customer. The BAME worker does not ask this to create divides between them and their customer. Nor do they want to stereotype their customer’s ethnic identity, but instead to share and equate familial experiences of struggle. Implicit in the question, asked by the middle-aged barber down Caledonian Road, is the question of roads travelled, how we settled where we are, in this present moment, not where we began.

I tell him of how I have not been to India nor Fiji and only once to Derby, the territories of my parents and grandparents; I was born in South London and the span of British imperialism is clear in my family’s movement across colonial territories to the heart of the empire in the UK, and then south from Derby to its capital. For the past three generations my family were brought up in starkly different areas. I know that his question ‘where you from?’ is not to hear exotic anecdotes of the east or Pacific Islands. He is trying to connect. He wants to give us both the opportunity to build affinity from our familial experiences of migration within the POC-owned environment. The generational gap in our conversation becomes clear when I hear of how he brought his family up in North London – his smile whilst saying so indicates I might remind him of one of his own children.

In a world where war over territory was just a foot away on the Turkish news channel, and where pop culture tracks like Kendrick Lamar’s vivid 2012 hit, m.A.A.d city, evoke paranoiac questions over territory (‘Fuck who you know! Where you from?’), these conversations in POC spaces build affinity, not division, among strangers and friends from different territories. It is refreshing.

* BAME = Black Asian Minority Ethnic

** POC = People Of Colour

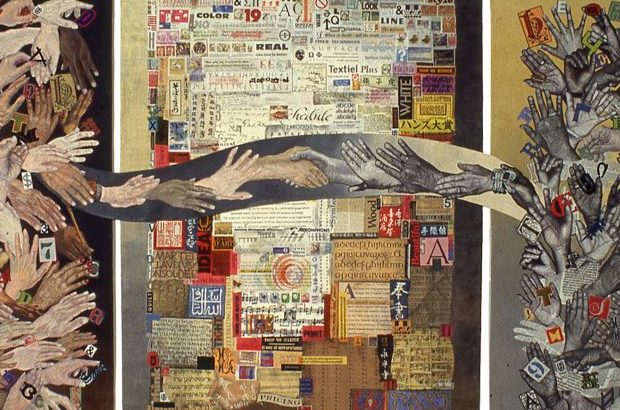

Artwork: B. J. Adams, Connecting (1998).