KACPER KOLĘDA reviews ‘Basquiat: Boom for Real’ at the Barbican.

More than twenty years have passed since the first — and last — posthumous exhibition of the works of Jean-Michel Basquiat shown in Great Britain at the Serpentine Gallery in 1996. Back then, the exhibition focused only on what was considered the ‘major’ works of this Afro-American artist. This year, however, the Barbican Centre curators, Dieter Buchhart and Eleanor Nairne, gathered together a vast array of works and influences providing what could be called the first complete monographic exhibition of the artist in the United Kingdom. As somebody with a profound interested in Basquiat, I had high expectations.

The exhibition space was divided into two floors, exploring the different contexts of Basquiat’s artistic development. The upper floor aims to place Basquiat in the context of his circle and artistic development from his first show onwards, while the lower is supposed to evoke the artist’s studio where numerous large-format works were presented along the books he used as references and sources of inspiration. In general, the exhibition concept seems to have a relatively standard formula, reconciling reflection on the works with biographical information. As Eleanor Nairne disclosed, their main aim was to ‘debunk the Basquiat myth’: the constructed image of a troubled, rebellious artist challenging social conventions in his notorious Armani suit. Noble indeed, but it seems to me that the curators failed to put their ideas into practice on several fronts. Ultimately, they convey yet another romanticised vision of the artist, emphasising a few chosen aspects of Basquiat’s personality, as well as from his artistic circle, and consequently, hindering a more open, honest reception of his work.

The curators’ vision focused on the cult of personality rather than formal attributes of individual works, creating the irritating impression of fighting one’s way through the curator’s idée fixe. It cannot be denied that the first posthumous exhibition organised by a major art centre must function on very specific rights: curators are faced with a task of concluding someone’s oeuvre and introducing it to a wide audience. Even if (as in this case) the artist has already become an element of pop culture, I believe the aesthetic of the work should still remain more important than anything else. After all, it is curators who, to a certain extent, have shaped the public perception of Basquiat in Britain. Here, however, by ignoring that responsibility, the resonance of the show was undermined and left me feeling mistrustful of what I saw.

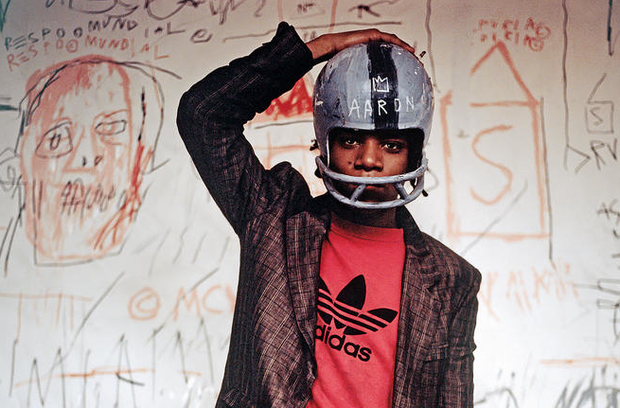

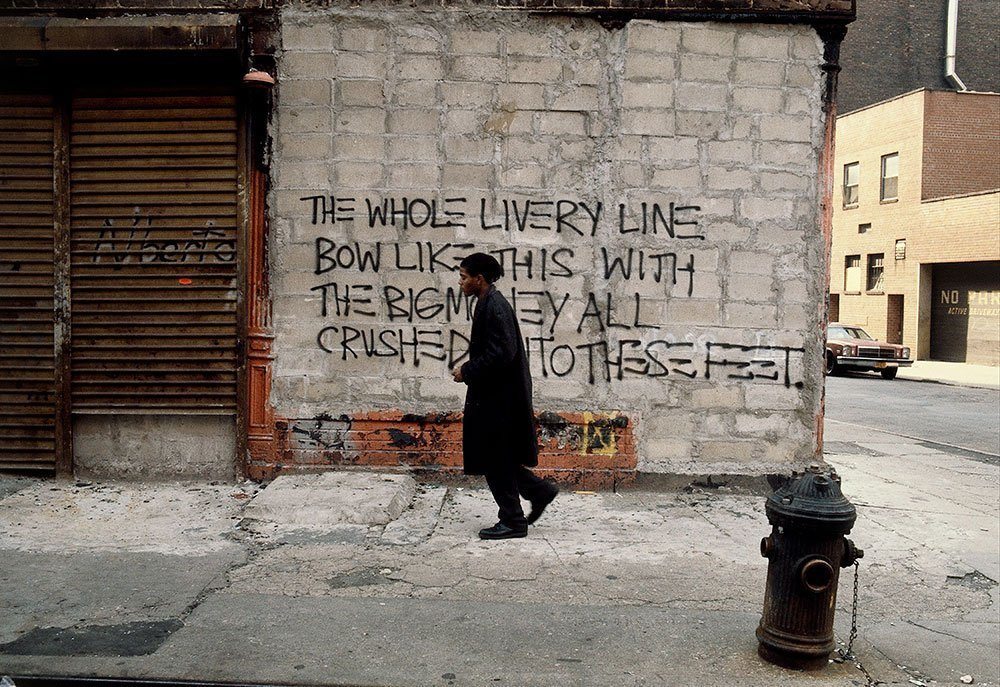

Upon entering the exhibition, you are first confronted by a video of Basquiat dancing in his studio. Visible from both the upper and lower levels, the clip is projected onto a wall. The clip was notably large, spanning the entirety of the wall from the floor to the high ceiling. This way, the silhouette of Basquiat accompanied the visitor along his/her journey through the artist’s life. A photograph on the wall next to the entrance is even more significant. What seems at first to be picture of Basquiat captured while walking down the street, is in fact a shot from the set of Downtown 81, a movie in which he played the main role. This staged still taken from Downtown 81 is the first image viewers are confronted with in the exhibition: Basquiat is displayed as an actor in a film. For me, this highlighted and encapsulated one of the main problems of the exhibition. He and his life are presented as spectacular and theatrical – perhaps even tragically beautiful. I found that this in particular was an ineffective and unproductive way to contextualise his work, as the film Downtown 81 was most emphatically a construct in itself. The exhibition becomes an artifice of Basquiat’s artistic development, relaying a romanticised history of Basquiat. A theatrical portrayal of a tortured intellectual’s artistic development isn’t very accurate if we bear in mind his actual story, right?

Photography and cinematography are recurring modes of display throughout the exhibition. As American essayist on culture and media Susan Sontag observed in her book On Photography, photography can and should be taken as a “tool of power”. The image of mechanical accuracy captured by the lens in both photography and film are imbued with a sense of ideological capture. By laying claim to this inherent mechanical accuracy, images captured by the lens in photography and film demand the observer to take the image as empirical evidence, as fact, and as truth. By utilising these two forms of media, the curators created the illusion of an animated Basquiat: smiling from the photographs, dancing in the films, talking in the interviews. This idealised construction of Basquiat’s persona is relayed in throughout exhibition. Lens-based media provides a contrived feeling of ‘reality’ and a trust in ‘accuracy’. However, the exhibition sustains an highly inaccurate image of Basquiat. For example, the subject of Basquiat’s death, and his drug addiction, are completely omitted. The exhibition reinforces the glamorised image of the ingenious artist: his life as a never-ending feast, full of famous friends and prestige.

Pretty incisively, in Questioning the Visible, English Art critic John Berger states: “every photograph is in fact a means of […] constructing a total view of reality”. The curators do indeed create this new version of the real world surrounding Basquiat through their choice of media. They present the artist’s image through the eyes of the people and places he worked with and in, yet they do not allow his works to speak for themselves. What’s more, glamorising an artist who struggled with drug-addiction is nothing short of morally irresponsible.

The curators make Basquiat their captive by using various media to forcibly place him in their chosen narrative. By this I refer to the inaccurate, idealised contexts they placed his works in. The actual artworks are partly eclipsed by all the photographs, captions and letters. Although the photographs and captions are credible testimonies that help to embody the atmosphere of the epoch, they nevertheless pull the focus away from Basquiat’s actual artworks. Room 4, The Scene, perfectly exemplifies this curatorial ambiguity of focus: the tiny cubicle of space recalls the spots of New York’s underground scene like The Mudd Club, which Basquiat used to attend. The captions on the wall mention splendid characters like Klaus Nomi, or Madonna. While visitors’ attentions are drawn to the collection of Maripol’s polaroids, which depict those characters important in this circle, Basquiat himself – with the few presented works – is pushed out to the margins, presented as a mere member of that elite, fashionable crowd. The emphasis is shifted from the artist to the circle of famous people he knew. This would have been perfectly acceptable at an exhibition dedicated to New York’s 1970s scene but, unfortunately, this wasn’t the case. The exhibition digressed from it’s original motivations. Boom for Real was designed as a monographic exhibition; however, in many rooms, Basquiat features as merely a supplement to the visual feast of New York’s bohemian circles.

Ultimately, curatorship is a great responsibility: every choice has both social and political importance. For this reason, it requires rising above personal tastes and views — this is overlooked in Boom for Real. The curators forget to leave space for the artworks to speak for themselves, thus denying room for interpretative thought and reflection. Sadly, Boom for Real did not meet my personal expectations. However, due to the incredible popularity of the show, this exhibition has hopefully opened doors for future Basquiat retrospectives.

Boom for Real is on display at the Barbican until 27th January.

Featured image courtesy of barbican.org.uk