ANISHA MÜLLER weighs in on the Lena Dunham debate, and defends her much criticised brand of feminism

In light of our 21st century culture of incessant tweeting, One Directionamania, and infinite OCD-related television (which now ranges from cleaning to Christmas), I’ve never thought of myself as an obsessive person. In the last few weeks, however, I have had to reconsider. Coming home from a party at four in the morning, in an almost routine manner, I open my laptop, and continue my Internet search, in the hope of finding a new essay/film/snack preference of the It-woman of our generation: Lena Dunham. What began as mild form of procrastination has led me to obsess over Dunham’s work and the female voice – and by this I do not mean my own one in a house of four male flatmates (as, luckily for me, none of them make it difficult in the slightest for it to be heard).

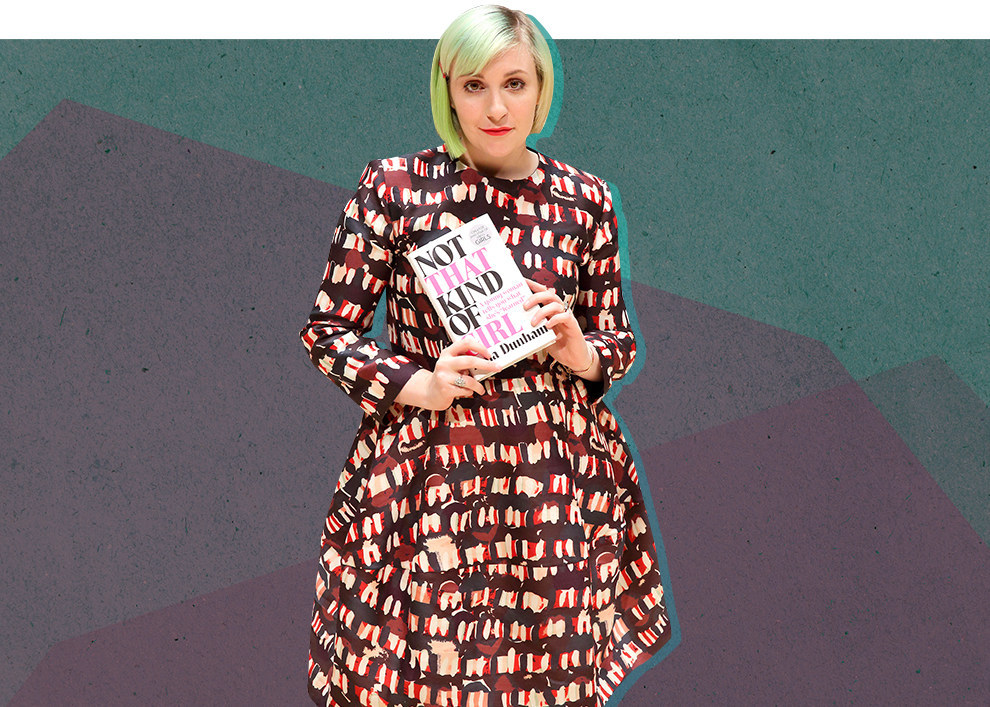

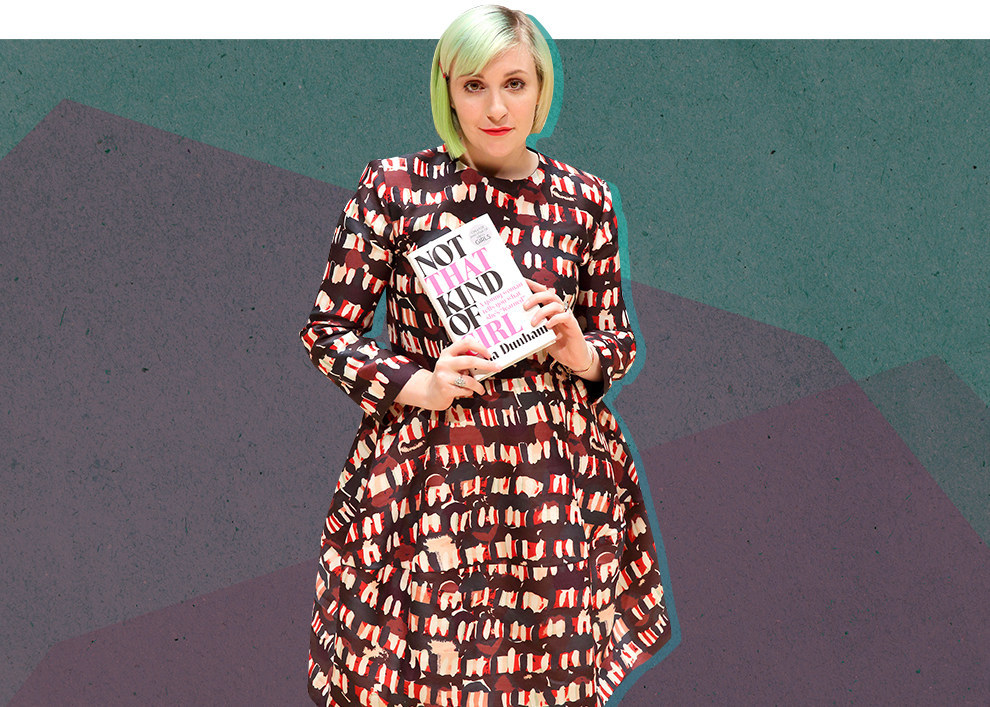

Her TV series Girls, and autobiographical essays in Not That Kind Of Girl are all subversive and certainly more complex than their titles make them seem. In fact, it is crucial that we do not judge her book by its (pink) cover nor her TV series Girls by its pointedly female agenda. It is true that Lena Dunham has managed to strike a unique feminist chord – and done so, as Caitlin Moran observes, in a time when the waves of feminism have long since been lost in the tide. However, Lena Dunham’s ultimate aim seems to reach beyond a discussion about women, for women, and solely by women. As she herself says, it is the ‘idea that the feminist conversation could be cool again’, among both genders, ‘and not just feel like some granola BS’.

http://www.buzzfeed.com/lenadunham/lena-dunham-why-i-chose-to-speak-out

Lena (maybe because of the intimacy of her works I feel its acceptable to call her by her first name, which it probably isn’t) by the mere age of 24 had already directed, produced and starred in the feature film Tiny Furniture. Since then her acclaimed TV series Girls has won three comedy awards, and her book Not That Kind Of Girl is undoubtedly going to appear in hundreds of girly stockings this Christmas. But being hailed a strong, female ‘voice of a generation,’ as her character Hannah in Girls remarks, does not come at a small price.

Lena’s work is inextricable from her personal life. Her characters are constructed by autobiographical components, therefore when Hannah is scrutinized by the media, so is her creator. In Girls, it is often impossible to tell where Lena begins and her character Hannah ends. Both are twenty-something female creatives, suffering from a combination of destructive relationships, self-criticism and varying degrees of an obsessive compulsive disorder. In these testing circumstances the audience has love-hate relationship with her. At times her victimisation seems frustratingly self-inflicted, but her quick-wit and sarcasm still manages to satisfy (what we like to think is) a truly British humour. In her quasi self-help book, her problems are never patronisingly ‘just like ours’. Yet her personal background and the way she deals with obstacles is central to a Lena-critique. In some reviews she has been reduced to a white middle-class artist whose feminist principles consist of ‘Too Much Information’ and being fundamentally self-absorbed. ‘Is this the essence of women of our time?’ the critics exclaim in horror. With the rise of invasive reality TV (Gogglebox is meta-television at its best) and hyper-narcissistic apps (Selfie Photo Editor now only £1.49) perhaps there is a truth in this. However, we must question if this is confined to the female gender.

Issues amongst today’s male youth are excused through ‘Top Lad Banter’- blurring more lines than even Pharrell Williams can count. Lena confronts these day-to-day instances of misogyny and sexual abuse by drawing on her own experiences. The graphic and un-Photoshopped sexual encounters in Girls on the surface are toe-curlingly awkward, but they also have subtly sinister implications. A reality that Lena has an acute awareness of is that in our generation sexism and sexual violation is not always clear-cut. Watching the encounters on screen the thought ‘hang on, is this acceptable?!’ repeatedly crosses our mind. It is particularly evident in her anecdotal essays, where the autobiographical form makes them even more disturbing. Her experiences are controversially told with a biting satire, even a humorous tone. In one essay, Lena’s friend with a ‘voice reserved for moms in Lifetime movies’ brings to light Lena’s own rape incident- to which she promptly bursts out laughing. It is this form of discourse- blunt, blasé, and bemused- (unsettling as it may be) that makes her work so relatable.

Lena’s feminist voice is honest and never aggressive, and the somewhat tired topics of body hair and pornography do not define her work. Undoubtedly, she reaffirms Carol Hanisch’s theory that ‘the personal is political’. Yet her role as a ‘pop-culture phenomenon’ does not derive from the regurgitation of 60s feminist writings. As she explores family dynamics, sexuality, anonymity, artistic expression, technology and mental health, her works extend far beyond the personal insecurities of one girl in her twenties. The insulting label of ‘Clit-lit’ is fundamentally invalidated. Lena’s aim is for both sexes to question a generation that seems to have become complacent with everyday inequality- where a female voice is rendered less important than that of its male counterpart. If this message falls on any deaf (twentysomething year old males’) ears, the then the least I can do is to remove Not That Kind Of Girl’s offensively pink cover, leave it in the toilet, and let my flatmates make sure they’re up to date on the rules of platonic bed sharing and the repercussions of being a ‘Hover-Spooner’.*

* If you are not planning on reading the book this refers to the politics of bed sharing; Lena recounts a specific instance in which the big spoon (a guy) hovers their arm over the little spoon (Lena) in a hesitant and amateurish fashion.