ELAINE WONG recounts the disorienting experience of growing up amongst several cultures.

Globalisation is often considered in purely political, economic terms, forgetting not only the social aspect but also how it effects individuals. Its impact is personally felt by Third Culture Kids (TCKs), a unique demographic who have been raised in several different cultures for a significant amount of time during their personal development.

A TCK’s first culture is inherited from their parents’ country, and they acquire the second from foreign countries they move to; the third culture implies the one that is internally created by the TCK in combining the different cultural settings that have formed their identity. There is no typical template background for a TCK, and none of them are straightforward. Take me as an example: I was born in Hong Kong and studied at a Canadian international school, and then spent my teenage years at a boarding school in the English countryside, before going to university in central London. Explaining the unique combination of cultures that have come to define me as a person is a mouthful to say the least.

Integration between countries is the core essence of globalisation, and the emergence of the TCK as a concept is in many ways a reflection of the increasingly globalised world we live in. The term was first coined in the 1950s by researchers John and Ruth Useem to describe the children of American citizens who were living and working abroad. Their studies revealed that individuals who have experienced this multicultural upbringing have distinct standards of social behaviour, work ethics, and overall understandings of society. ‘Third culture’ became the generic term to cover these distinct standards, which are arguably formed as a result of TCKs relating different cultures and societies to each other.

Tracing the individual journeys of TCKs reveals similar issues repeated across diverse geographical locations: on one hand it is remarkable how swiftly initial integration into a new community can happen, while, equally, long-term assimilation throws up myriad challenges, coupled with the complexities of a nomadic life. Issues relating to bureaucracy and social alienation become facts of life for TCKs at a young age.

With the learning capacity of children, many TCKs become quickly adept in the language of their new country. However, sometimes even being fluent in a language isn’t quite enough. You have to know the lingo too. The linguistic quirks of English, in its various forms, are sometimes difficult to navigate for non-native speakers. From confusing ‘chips’ and ‘crisps’, to inadvertently asking my friend if I could borrow her ‘pants’ instead of her trousers, I’ve experienced many moments of accidental miscommunication. While these are embarrassing at the time, they are also lighthearted and actually speed up social assimilation. They serve as ice breakers, and alert members of the TCK’s new local community to cultural differences that can be hard to articulate directly.

There are more thorny and long-lasting barriers to assimilation for TCKs. As a consequence of being multilingual, they are bound to have a slightly ‘odd’ accent in whatever languages they are fluent in. According to the International Journal of Bilingualism, multi linguists displaying an ethnic accent speaking English—one that doesn’t clearly proclaim them as American, British, Canadian, Australian or Kiwi—are perceived as foreign, regardless of fluency. People make subconscious assumptions about someone’s country of origin based on their accent; this process is complicated in the case of TCKs. My hybrid accent is somewhere between Canadian and British; in the UK people often think I’m American, and people at home think I’m British. Often a single element of a TCK’s identity is taken to be representative of the whole person, because it is easier to distinctively categorise someone as either an outsider or insider–there is no in-between.

After spending some time in England, I gradually became more like a foreigner back in my hometown–even by people I didn’t know. A saleswoman at a Hong Kong supermarket once tried, before I could say anything in my mother tongue, to sell me some seaweed by telling me in broken English how to cook it, imitating bubble noises to convey the word ‘boil’. Since to the best of my knowledge I look 100% Chinese, it seemed strange to me that she had assumed I wouldn’t understand Cantonese. It seems that, along with creating a ‘third culture’, TCKs also manifest a ‘third demeanor’ detectable by locals, causing an alienation in interactions with a person’s first culture, too.

The (almost too) adaptive nature of being a TCK makes a straightforward identity impossible. A TCK can never become truly native in the eyes of any local community, regardless of how much of that community’s culture they assimilate. According to Dr. Danau Tanu of the University of Western Australia, as a result of exposure to different cultures at a young age, TCKs develop a higher level of ‘intercultural sensitivity’ – a TCK is a ‘cultural chameleon.’ This is strenuous: our multicultural identities are constantly challenged, as people with more straightforward backgrounds try to fit us into their own ‘mono-cultural mould’.

While governments and organisations like the U.N. promote globalisation, immigration is (as is becoming more and more apparent) a contentious national topic around the world. This leaves TCKs in a difficult position: their complicated backgrounds make determining where they are ‘from’ less straightforward. They are often dismissed as suspicious. Thanks to Brexit, TCKs from or living in European countries will soon be revising a lot of legal documentation. A nomadic lifestyle means accumulating an ever-increasing number of entry stamps on your passport, which always leads to suspicious questioning from immigration officers—in order to apply for a Tier 4 Visa, you have to recall and fill in the exact dates of all your past entries into the UK, for instance. These bureaucratic processes are complicated for everyone, but are especially troublesome for TCKs, who have to go through them in their juvenile years over and over again. With each time, successively, there are more details to fill out and explain, and an increasing risk of getting deported.

The interactions of TCKs with local communities reveal that conceptions of what it means to belong to a society are often cast in black-and-white. The notion of ‘not belonging’ can generate hostility, but more often than not problems are more subtle. Whilst being a TCK can mean having a lot of eccentric stories to tell, having such a mosaic identity is undeniably stressful – both on legal documents and in the mind of the individual. Nevertheless, no matter how messy and convoluted my life history is, I am proud of everything that makes me who I am: a Third Culture Kid.

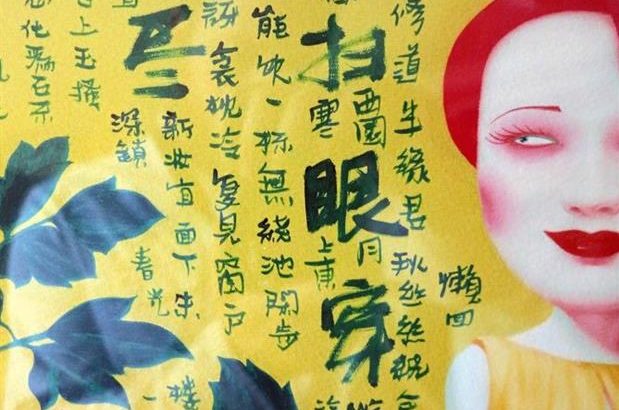

The Featured Image is by Feng Zhengjie, courtesy of Hotel Art Fair.