MATTHEW WAGAINE discusses the interaction between ethnic and queer identity, and what increased corporate sponsorship at Pride parades means for QTIPoC.

Within popular culture, blonde hair is synonymous with a standard of beauty to which we are all supposed to aspire. For non-white performing artists, dying one’s hair blonde is often a sign of divorcing themselves from their ethnic roots in an attempt by the record label to appeal to a mass audience. For instance, Shakira, one of the world’s most popular artists to come from the Latin American scene, made her big international breakthrough in 2002 with her hit, ‘Whenever, Wherever’. The accompanying music video showcases the performer shaking her famous hips with long, curly locks of cool blonde hair. But whilst her hips weren’t lying, what most of her international fans do not know is that in the years prior to her Anglophone debut, she donned jet black hair. Shakira’s new blonde look signalled that she had in fact ‘arrived’: she was now recognised as a global superstar.

Across campus, I have noticed an increasing number of my gay and bisexual male peers dying their hair blonde. Similarly, bright neon colours are a favoured choice by many LGBT+ women and non-binary people (equipped with an undercut, of course). Any drastic aesthetic change is bound to be met with shock and awe from friends and strangers, but in both situations, these reactions are typically based on assumptions made about the individual’s identity: in particular, the assumption that this person is in full control of their identity, and choosing to emphasise their queerness. As if, like Shakira, they have finally arrived onto the scene, and that there is no going back now – their hairstyle is an instant indication that they do not prescribe to the cis-hetero norm.

Expressions of art have always been a vital tool in liberation movements, reflective as they are of the internal conflicts that people suffer in the face of marginalisation. Music, film and fashion provide ways to mark our territory, take up space and spread the word that we are here to stay. As such, this need for a queer aesthetic is perfectly understandable. Carving out an aesthetic not only makes you identifiable to those who share similar experiences, but also identifies you to those who would much rather you didn’t exist, and conveniently spites them in the process. The trouble, however, with fixating on what’s on the outside, is that we overlook and alienate people within the community who don’t look ‘queer enough’. Just because their outfits aren’t Instagram-worthy, and their music tastes don’t fit into any of the playlists DJs play at that bi-monthly Dalston basement bar party you frequent, it doesn’t mean that they are dull.

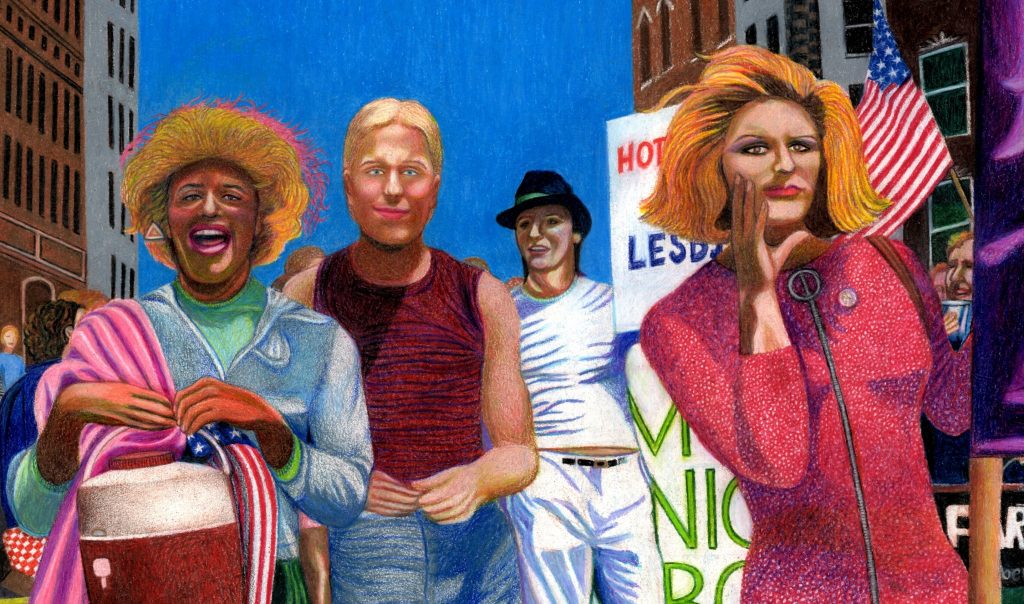

When these ‘un-queer’ interests and looks become closely associated with one’s ethnic background, we then have to confront a history of whiteness being prioritised above all else; a history that explains why the modern face of the LGBT+ movement tends to be cisgender and white, despite the fact that those who kick-started the liberation movement in June 1969 were trans women of colour (Marsha P. Johnson and Sylvia Rivera); a history that explains why many people, regardless of race, perceive being LGBT+, and acceptance of the LGBT+ community, as a white thing; a history that explains some people being shamed for their non-white heritage and actively discouraged from embracing it, and others being able to appropriate that exact heritage as and when it’s convenient.

The ethnicities of QTIPoC (Queer, Trans and/or Intersex People of Colour) are just as important as our sexual identities, and need to be expressed. It is therefore frustrating that we have to compromise to fit into queer spaces – to choose between being hip by bowing down to euro-centricity, or being square by embracing our heritage. A couple of years ago, I went to Brighton with three friends from KCL, who I’d met at some inter-university LGBT+ socials, and this became clearer than ever. We were looking for a place to go out and came across a gay bar, which the first of our quartet – the only white person in our group, who at the time donned a dark blue bob – entered without any fuss. When it came to the remaining three of us, the bouncer asked if we were aware that the establishment we were about to enter was a gay-friendly venue, and if we were OK with that. All three of us responded with an instinctive internal eye roll: we were not only OK with it, but a part of the venue’s target audience.

Internalised homophobia and transphobia may well play into the resistance of these fashion and artistic trends by QTIPoC. That said, it can also come across as condescending and tone deaf to imply that us poor PoC folk aren’t privileged enough to step outside of the box — in reality, we aren’t necessarily wary of what our families might think, we simply want to express other aspects of ourselves.

Furthemore, as Pride becomes increasingly commercialised, with more corporations jumping on the rainbow-coloured bandwagon in a bid to tap into audiences they had previously shunned, particular trends seen amongst LGBT+ people – that radical queer aesethetic – will be commodified. Many of the companies capitalising on these trends will not be treating their LGBT+ employees with the same level of respect as their cis, straight contemporaries, and these newly commodified trends may not actually provide the suitable wriggle room needed to explore your own identity. Last year, Zara launched a gender-neutral clothing range, which consisted primarily of plain white tees, pale jeans and light grey hoodies. Attempting to increase the visibility of a typically invisible section of society via extreme minimalism is hardly liberating.

As London Pride grows in size and scope, sponsorship becomes necessary, and we are at risk of marginalising those that do not cohere to the shiny corporate image this demands. Within the London QTIPoC community, there have been moves to counter this threat to inclusivity at mainstream Pride – which at the Reykavik Pride parade has seen corporate signs banned altogether. Launched in 2015 by QTIPoC artists, the Queer Picnic offers an alternative to the commercialisation of mainstream Pride, and remains a crucial space for people like me whose queer identity and ethnic identity cannot and should not be viewed separately. Both identities interact with one another and heavily influence the way I am perceived by people, and the consequent reality in which I live. The problematic lack of cohesion within the LGBT+ community is caused by the refusal of some of its most privileged to acknowledge this, to acknowledge that the things that make us different – things like gender expression, ethnicity, physical and mental ability – present each of us with different struggles.

As the temperature rose on the first day of July this year after a disappointing wet spell the previous week, spirits at the Queer Picnic ascended. A blend of R&B, reggae, bhangra and other culturally specific music genres were blasted from the speakers. Thankfully, no Lady GaGa/Katy Perry-inspired ham-fisted empowerment clichés were heard.

The Queer Picnic is an annual event that took place on 1st July this year, one week before the official London Pride parade. More information about this year’s picnic can be found here.

Featured image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.