ARVIND IYENGAR discusses Beatnik legacies and doomed road trips in Dead Ink’s revival of Baby Driver by Jan Kerouac.

Born just a few months after her parents’ separation, Janet Michelle Kerouac was the only child of Beat Generation author Jack Kerouac and his second wife, Joan Haverty. She never met her father until age 10, when Jack chose to take a paternity test to unsuccessfully disprove his fatherhood. At 12 she was briefly in an NYC girl group that wrote a novelty love song to the Beatles. She later found a close confidant in her father’s biographer Gerald Nicosia, and spent the majority of her life in abject poverty and the consequential revolving door of mental institutions, juvenile detention, substance abuse and prostitution. She eventually died of kidney failure at 44. While this brief biography depicts a lifetime involuntarily lost to tragedy, Jan Kerouac’s debut was a prolific memoir—redefining and responding to the conventions of a literary subgenre previously headlined by her father.

Jack Kerouac’s divisive yet seminal work, On The Road, exemplified the quintessential American road trip. Set against the backdrop of the Beatnik counter-culture of psychedelics, sexual liberation and defiance of economic materialism, the ghost of this literary road trip can be felt throughout Baby Driver.

Jan Kerouac adopts a similar approach in a travelogue-style record of her escapades to Mexico, Europe and South America, her rebellious stints as a prostitute and a groupie for drug dealers, and her several short-lived, tumultuous romantic encounters. However, rather than promulgating or even presenting a net-positive case for this lifestyle, the cruel irony of Jan’s fate is a systematic demolition of everything advocated for and built up by previous male-dominated liberationist Beat Generation ideology.

“I remember a certain gullible part of my young mind thinking that nine and a half must be the age when one was grown-up enough to meet one’s father for the first time. It meant I was maturing—a big girl now.”

The narrative is disordered and fragmented, with each chapter drifting between past and present, to provide highly detailed, densely packed exposition from distinct vignettes of several formative periods in her life. The abrupt and drastic tonal shift across consecutive chapters reflects the fragility of human existence itself—especially when borne from a cradle of unpredictable parenting style, barely conducive cultivating environments and stark deprivation of emotional security. The visceral nature of the narrative is already palpable in the first chapter, which drifts from serene descriptions of a rural tropical paradise to recounting experiencing a stillborn childbirth at the age of 15 and only being able to feel relief. The structure is intentional in its irregularity, inducing the nauseating ennui that Kerouac feels from her inherited vagrant life of instability. She desires stagnant solace in cookie-cutter domesticity but finds only heartbreak and rejection. The desperation for some kind of stability in relationships and circumstances is epitomised by a fixation her prepubescent self had with a peach hanging outside the window of her stepfather’s suburban residence in Missouri. Despite the grimy distortions of the window which filtered her perception, the author feels dejected about having to leave before the peach could ripen sufficiently.

“I’d sit evenings as Phoenix cooled down to eighty-five degrees, and count my stacks of loot, rearranging them from wads to stacks to fans to rolls to lines to regiments and circles and back to a huge stack again.”

The disorienting back-and-forth storytelling style serves as the perfect characterising vehicle for the protagonist. Jan as the speaker is a reinvention of the Don Quixote archetype in literary tradition, a disillusioned, morally flawed protagonist who hinders her own prosperity whilst grappling with inner demons upon the boundary of reality and fiction. As opposed to the boyish, rebel mavericks we see in the masculine quixotic or the existential/identity-crisis sad girl trope, Kerouac deconstructs the psyche of not just a woman but a human consciousness flailing for coping mechanisms to avoid feeling or confronting the omnipresent ‘demon’ that haunts them. This escapist, avoidant yet deeply hurt persona blends popular archetypes of the emotionally unavailable, self-destructive man with the emotional intelligence (or at least awareness) and deeply passionate grief of the pejorative ‘hysterical’ woman.

“I should never have let him think that he was my reason for coming to South America. If I had just been brave enough to admit that it was only the trip I wanted to experience. What a shameful opportunist I’d been. That was the demon inside me. I thought I understood then what Venus in Capricorn meant, or could mean at its worst…the planet of love in the sign of use, the mark of the prostitute.”

In each chapter, the reader is thrust into a distinct corner of Jan’s desires, idiosyncrasies, experiences or subsequent misgivings. The lack of explicit exposition invites the reader to follow a breadcrumb trail across the character’s own fractured existence to collect a coherent, psychoanalytic mosaic. The non-linearity of the narrative is faithful to the character’s experiences of these events. The lack of psychological comfort or security from a young age results in her finding comfort in either psychedelics or distractions that whisk her off from the heavy spectre of both her past and present.

The reflective nature of her narration pays homage to a defining feature of the road trip literary tradition, which uses the forward-facing journey to unintentionally trigger reminiscence. The irregular passage of time ties together the past and future profoundly, revealing the flawed, self-sabotaging Jan as simply a collage of scars and emulations. These clues—like Jan’s obsession with horoscopes stemming from her longest relationship with a hippie occultist called John—peel back the complex layers of the protagonist.

“[I] had $800 dollars, and I was going back to Santa Fe. Playing hide and seek with truck drivers now on my merry way back to the mountain refuge, I was like Marco Polo bringing home wondrous bounty to amaze the folks back home.”

Finally, returning to the inheritance of her father’s Beat Generation influence—Baby Driver exposes the tragic irony of the subculture’s obsession with unfettered, almost anarchic liberation at the cost of their own well-being—and of those around them. The transition of Jan from a jovial young girl who enthusiastically follows her unstable mother around in all her misadventures to a tragic young lady stumbling through promiscuity, substance abuse, and institutionalisation is neck-breaking in sincerity. Like a restless child, she is always looking for the next anaesthetic vice that could push her cognisance beyond despair and grief, towards a rationalised detachment from where she can watch herself fall apart and somehow float back together. She narrates the most heart-wrenching instances of her father’s neglect, abusive partners, inhumane stints in rehabilitation, and existential rotting with scathing self-awareness.

“‘Somehow…I know you’re right,’ I sniffed, drying my eyes, ‘but my emotions won’t listen to my mind.’”

The shadow of her father looms large over both her writing and experiences, but Jan Kerouac time and again proves that she doesn’t deserve to be overshadowed by his mantle in any way. The emotional depth and maturity she shows in the treatment of her characters is judgemental yet absent of any vindictive blame—she even forgives her father’s absence as the sign of a higher calling. The life of the author that we essentially live out alongside her in these 200 pages is not a grand philosophical statement but an exploration of the way that an unhealthy obsession with the Beatnik ideals of ‘letting go’ can result in drowning in one’s own self without anchor. The vagrant, drifting nature of this genre is shown to be a crisis disguised as an epiphany. In broader terms it also speaks to the infinite complexity of human existence, especially grief—which isn’t a decline or spiral as commonly characterised but rather a rickety rollercoaster that takes the defiant individual to maddening heights. And despite knowing the inevitability of an eventual fall back down, the cursed few will voluntarily choose to tag along for the ride—a temporary, doomed respite from the coarseness of ground reality.

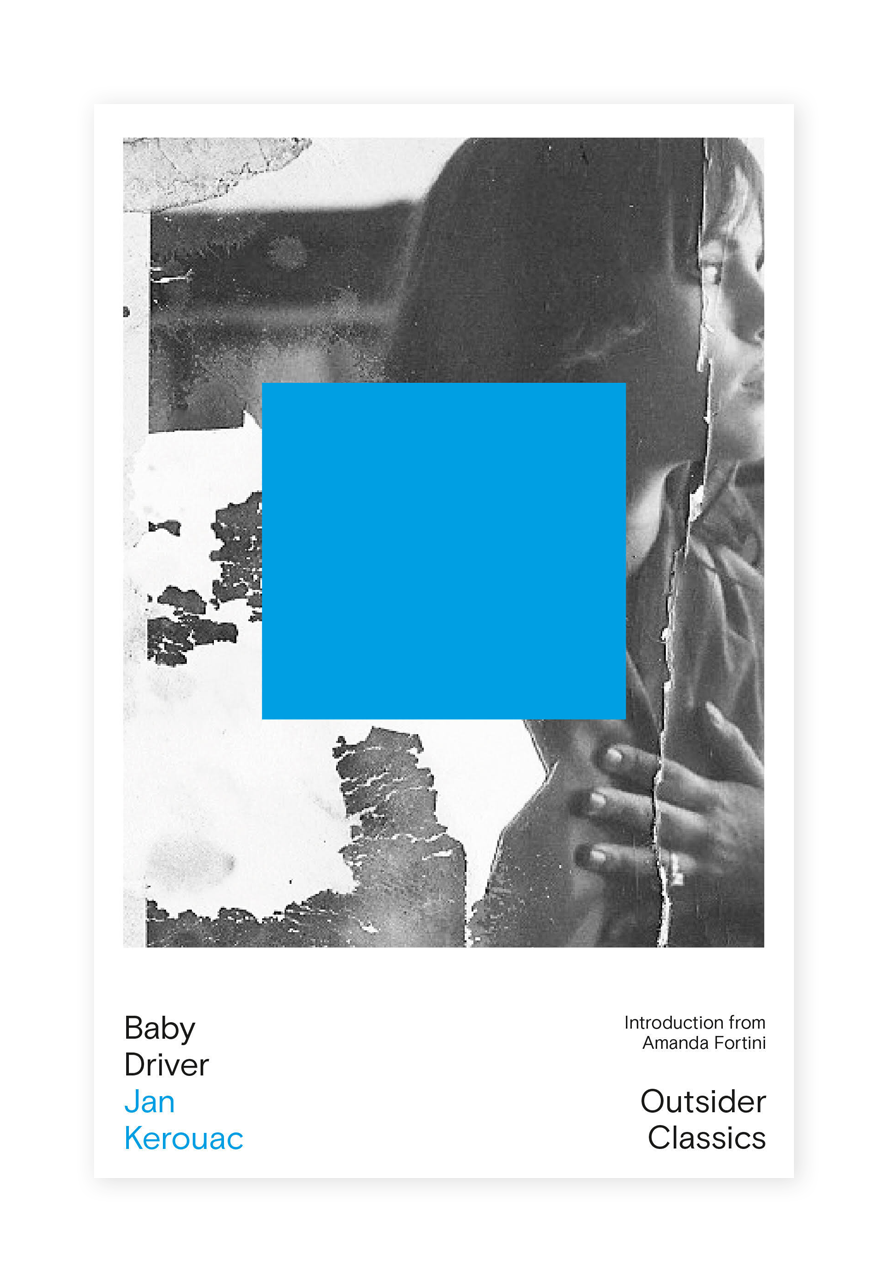

Baby Driver is available through Dead Ink from October 23rd, 2025. Featured image courtesy of Dead Ink.