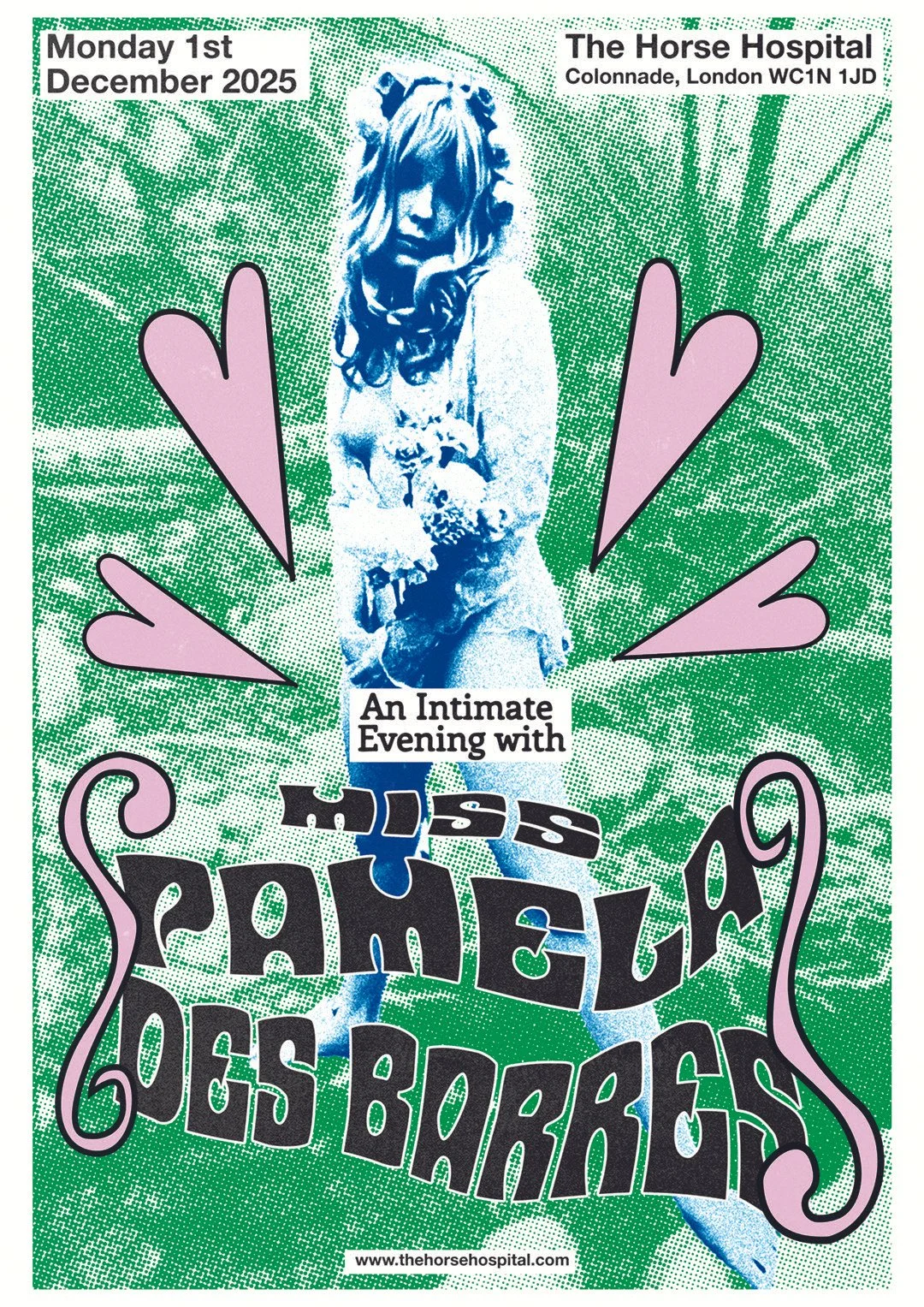

Literature sub-editor MADDY JOSEPH attends Pamela Des Barres’ reading at the Horse Hospital.

On 1st December, The Horse Hospital hosted an intimate evening with writer and “queen of the groupies”, Miss Pamela Des Barres. Part-reading, part-performance, the event reframed her 1987 memoir I’m With The Band: Confessions of a Groupie into a living, breathing document, a narration of her very own place within music history.

The evening began with a performance from musician Ray Williams. Her cover of Beatles’ “Love Me Do”, complete with harmonica, transported the audience back to the 1960s. Williams’ original tracks “Planet California” and “Fantasy” explored American and groupie culture, whilst her performance of “Sweet Georgia Pines” marked one of the evening’s most tender moments,using lyrics Des Barres herself had written about Gram Parsons.

Even before she addressed the audience, Des Barres’ presence was unmistakable. She moved around the space in a multicoloured gown layered over a lilac lace dress, sparkly heels, patterned white tights, blue lace gloves, a flower crown, and star bunting draped around her neck. Later, she summarised her fashion philosophy: “I love clothes. I don’t dress my age and I never will. Everyone should doll themselves up”.

Although the event centred on readings from her memoir, Des Barres treated it less as a linear text and more as a prompt for conversation. Once on stage, she immediately disrupted the conventions of a reading. She encouraged us to get comfortable: “You can even take your clothes off”. Des Barres regularly paused to speak directly to the audience, playing excerpts of the music she referenced and singing along while urging others to join in. The result was an informal, often chaotic environment, as she let the room and the crowd shape the reading with her.

Des Barres’ stories returned to her adolescence in the 1950s, to her early fascination with musicians. She read entries from her teenage diary about Beatlemania, including an enthusiastic, if anatomically focused, description of McCartney, and described the rituals she devised to ensure they would meet. She recalled asking herself, “What does it mean to treat Elvis nicely?”. These early obsessions foreshadowed her later proximity to the musicians who would come to define rock mythology.

She moved through early encounters with rock’s most canonised figures. At seventeen she met Jim Morrison “in nothing but tight black pants”, kissed him backstage while high, and accidentally wandered onstage during a Doors performance. She described starring in a Jimi Hendrix Experience film and rejecting Hendrix’s advances, deciding instead to “save [her] virginity for his bassist”. Reflecting on Frank Zappa’s influence, she said, “Zappa made me fearless”, and added, “When women tell me reading my book made them feel fearless, I think, ‘Oh my god, Mr Zappa, I’m doing my job’”.

Her anecdotes unfolded with the rhythm of oft-told stories and with a palpable refusal to let them calcify. She recounted becoming part of Zappa’s all-female group GTOs, buying Rod Stewart his first feather boa, meeting all four Beatles, dating Jimmy Page until his infidelities surfaced, and then beginning a relationship with Mick Jagger- “number one on my fuck list”, as she put it. She remembered writing as a teenager, “Someday I would touch and feel Mick Jagger, I knew it”, later adding with satisfaction, “And I was right”.

The Q&A section captured Des Barres’ sharpest, most unfiltered mode. When asked how she deals with people who claim groupies reinforce misogynistic dynamics, she didn’t hesitate: “I want to fight them all, with my fists if I could”. Her motivations, she insisted, were never passive or transactional, “I just love music and I love the people who make music. I would have been a musician if I could, but the opportunity just wasn’t there for women”.

Another audience member asked whether groupies still exist. “There are still groupies”, she replied. “There are always going to be groupies. People will always want to be with the people who make them feel good”. When a woman challenged her about writing openly about “sex with rock stars”, Des Barres replied, “I’m sorry you didn’t get to sleep with Mick Jagger like I did”.

These exchanges revealed not simply nostalgia but an ongoing defence of her own cultural role as someone who refuses to let others define or sanitise her experiences. By the end of the evening, it became clear that Des Barres’ intention was less about preserving a vanished era and more about maintaining authorship over her life. Her stories, even the familiar ones, were delivered with clarity, irreverence, and an insistence on framing desire, admiration, and participation as forms of agency rather than footnotes to male genius.

At The Horse Hospital, Miss Pamela Des Barres wasn’t reminiscing, she was reinterpreting.