Theatre editor SARA STEMMONS reviews Timelapse’s new cynically funny electro-folk musical, Precipice, at the New Diorama Theatre.

2025 is now hundreds of years old.

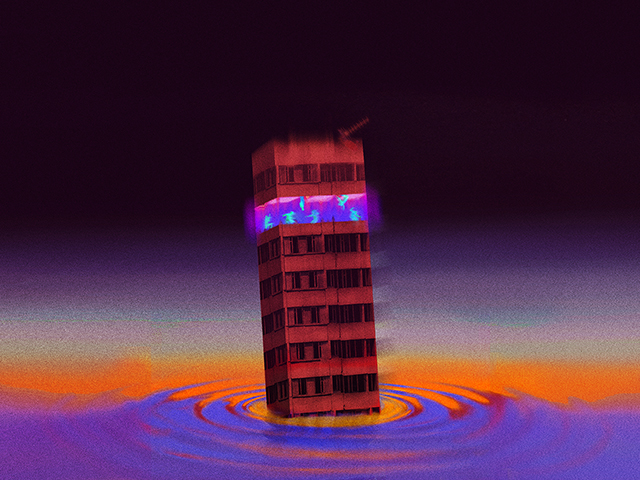

It is now the 300th Founder’s Day, and the five hosts ponder, “how did they make a sandwich?”,as they look back to the apocalyptic disaster of 2145 (an uncertain estimation from a fleeting year reference in a song and some pre-GCSE mathematics). This is the future of the future. The play begins with an introduction to the ceremony by Maggie (Isabella Marshall), who includes us in the small community that has grown from sparse survivors of the catastrophe. Not only does the setting of the ceremony serve the obvious purpose of immersing us into the dystopian world of Precipice, but it also answers what many musical-theatre adversaries ask: “Why are they singing?” They are singing because it is an annual ritual concocted by the founder, Robin Clark, to maintain tradition and balance in a newly established community, one constantly on the precipice of destruction. Security and stability is a fantasy constructed to mark the time passed since the day that washed away the world that we know; this tower has teetered on dilapidation for centuries.

Through jumps in time between now (2425) and then (2025), the narrative prods at our ingratitude the 21st-century self-destructors. “They had everything to live for” is what the tower-dwellers mourn. “They” is us, the audience of the New Diorama Theatre. A first aid kit, knives, and soup are all far-off fantasies for the generations that live off whatever was left behind in this archaic 21st century apartment, pre-man-made disaster. This world is a consequence of having it all but wanting more—of not attending to what is happening right in front of us—or right behind us: “They climbed up the stairs without noticing that the stairs were disappearing behind them”.

Creator Adam Lenson wrote that the central research topic in the collaborative, playful process that birthed Precipice was ‘The Doomsday Clock’. We see our present accelerate towards a “doomsday” . The end for Emily and Ash, our 2025 lovers, is defined at the beginning. We see their averagely tumultuous relationship develop, it becomes apparent that society not only does not consider the consequences of the present on the future, but as individuals, we are often so blindly preoccupied with our own trajectory that we neglect the trail of waste we leave behind us. The stairs are not sustainable, they never were, and now they are “disappearing behind us”. Our earth trembles beneath us as it does at the base of the tower.

Humanity’s’ meeting and repeating of doomsday provides a simultaneously disconcerting and comforting sense of pre-determined narrative for the play. The penultimate song of act one traces the broad history of humanity in the face of apparent annihilation: they begin with singing of the 1348 Black Death, moving through the nuclear age, toCOVID, and beyond into a past for them that is a future for us. This existential pagan-toned rock ballad imagines—or predicts—a terrifyingly possible war of 2060 that kills 4 billion people. Each time humanity believes they have encountered the end of the world, “but they survived”. They delight in a hope that humanity somehow always finds a way to survive, but also cautiously wonder how many times our self-destructive race can resurrect itself—surely our luck must run out eventually.

As the tower-dwellers are faced with annihilation, a result of the innately human abuse of resources, an optimistic remark sprouts from the anarchic anxieties: “we’ve been through worse…everyone says it’s the end of the world, but it isn’t”. But what if it is? Perhaps we are doomed to creating our own doomsday. Hopefulness and pessimism are held in a delicate balance.

This balance is fundamental to the structure of the tower’s community. For 300 years, a micro eco-system has functioned within a meticulous construct: a quasi-utopian self-sufficient body in fragile equilibrium that is held up on intangible principle, prone to crumble into the toxic waste beneath: there is one musician, one mathematician, one gardener and so on. Each clings intensely to their inherited craft, which provides a purpose for their bleak existence.

What keeps this tower above the waste is this symbolic ceremony that we are integrated into, the nucleus of which is revealed to be a Jacksonian Lottery, or “tombola”. Each year the community votes for who they believe has the most potential. Those names go in a vintage bingo cage, and one is picked out by Maggie (whether she was elected leader or inherited it is ambiguous). That person of potential must leave the tower. To search for what is out there is the optimistic spin on an exile into certain death that they all accept – a Tessie Hutchinson-style execution. This sinister truth lies at the core of the tower community. We hear over tape that the founder describes the tower as having ‘no visible crack’, which is what identifies it as a hub of hope and survival; but cracks found their way in nonetheless.

I would be doing a disservice if I did not discuss the music. Lenson adores musical theatre, for it is a medium that “can hold several dimensions of thought at once: ideas, images, contradictions, all threaded with urgent emotional currents”. I have attempted to convey these “several dimensions” in my writing, but where text falters, song excels. The agonising hope, the captivating fear, the beautiful sorrow of this oxymoronic microsociety is encapsulated in its music. Electro-folk? Possibly the long-lost term to define Highway 61 Revisited? Perhaps a term that can only inhabit 400 years in the future? Nonetheless, a term that can only be comprehended through sound. Electro for its hyper-modern setting. Folk for its fundamental seed in people. Folk music is ageless, often authorless, two qualities that scaffold this show. Time is shrunk and extrapolated. Music is passed town from ceremony to ceremony, not to mention the authorless-ness of the show’s division: “no single idea, lyric, or bar of music can be attributed to a single author” explains Lenson. Song is sung in an intimate setting with the purpose of passing down stories and continuing traditions—Seeger would be proud.

So, Maggie, Piper, Emily, Biscuits and Leo recount the past as their future destabilises beneath them. They sing, they laugh, they argue, they revolt, they repeat rituals as they close their eyes to the looming dilapidation of their structures, just as Ash and Zoe did 400 odd years before. They use empty water canisters to cover up the ruin outside like using a cheap plaster to cover up the wounds Zoe and Ash did 400 odd years before. People perpetuate their own demise from over-indulgence and lack of care for the structure that holds them up, just as Ash and Zoe did. Repetition of destruction, repetition of survival, but could there be a crack forming in this cycle? Perhaps it is true,“We can’t outrun the sun”.

Precipice ran from November 11th to December 13th 2025 at the New Diorama Theatre.

Image courtesy of New Diorama Theatre.