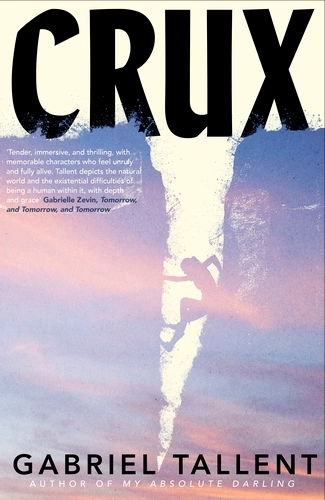

AALIYA MCKEE discusses unreality, coming-of-age and escapist climbing in the Californian desert, in Crux by Gabriel Tallent.

Crux follows the coming of age of two teenagers, Dan and Tamma, against the backdrop of the rough, unforgiving landscape of the Californian desert. The core pillar of the novel is the close bond between the two, who despite their different situations and prospects, share a love of rock climbing, and dream of a life spent traversing the wild spots of America

Tallent contrasts the open, free world of climbing with the characters’ increasingly troubled and empty home lives. Descriptions of the unforgiving rocks and the burning desert landscape permeate the narrative from the very beginning, and neither the author nor the characters sugarcoat the roughness and the brutality of climbing and the Californian landscape. The first boulder they climb is described in unflinching, unromantic detail, in a grimy parking lot “full of discarded tires, shell casings, and used condoms, with plastic bags snaggled in the grickle-grass.”

Even when Dan and Tamma move to climbing in the national park, the environment is just as merciless. Tallent makes the infliction of damage on bodies by the landscape conspicuous from the start—through cracked nails, and bruised, bloody skin. The novel is effused with visceral descriptions of the duo’s increasingly ravaged bodies, symbolising a brutal yet very concrete existence totally apart from the joyless, disconnected lives of their families.

However, the world of climbing remains a positive one, allowing Dan and Tamma to escape their difficult home lives and the empty futures that grow ever closer as the novel progresses. The burning desert landscape of blue sky and Joshua trees, rather than being the romantic California of the American dream, is one of lost hopes and suburban despair, as seen through the two characters’ deteriorating families, and their mothers’ severed friendship and broken dreams.

Dan and Tamma’s dreams about a life of rock climbing convey a feeling of nostalgia for a now-forgotten America that they believe can be found in its wild landscape, an America dismissed by others as an unrealistic pipe dream. Wild climbing becomes a version of the unattainable American dream, that for Dan is eventually erased by the draining corporate life of 401ks and “nice coffee mugs” that his parents push him towards.

Climbing in the novel is tethered to both the increasingly unreal idea of the lost, wild America destroyed by modern society, and the very concrete reality of the rocks that Dan and Tamma sweat and bleed to climb. Tallent explores the disparity, especially in Dan’s eyes, between this physical, tactile world of climbing and the rocky landscape, and the unreality of ugly, hopeless suburban life. The detailed descriptions of the physical limits Dan and Tamma push their bodies to contrasts with the detached way in which Dan sees his family and life prospects.

The novel also engages with mental health, with Tallent showing how climbing becomes a way for Dan to cope with his depression. The physical nature of it as well as his close bond with Tamma are the only things not effused with the unreality that pervades the rest of his life.

The novel celebrates the value of real connection with the natural world and others in coping with mental health struggles. Its setting in the early 2010s, largely untouched by today’s singular relationship with social media and AI, highlights how we have become even more isolated from both nature and each other in the last fifteen years.

The ending chapters of the novel also reflect this, with Dan stepping out onto his college campus encased by brick buildings, with “the horizon nowhere”. The wild natural world has now become unreal for him; the once-familiar “Wonderland” of “rust-red buckwheat and junipers” is now only a distant dream. Tallent pushes us to reflect on how our increasingly industrial world isolates us from nature, with the “leafy green trees” of the university quad being a poor substitute for the “vast and golden wilderness” that Dan has left behind.

Near the end of the novel Tamma herself says—“The top is only a symbol, and without the crux it refers to nothing. The crux is the heart of the boulder.”

With Crux, Tallent doesn’t show the characters reaching the top; neither of them get a perfect, or a happy ending. He focuses on the struggles they go through—the cruxes they reach, through physical climbs, or the family hardships that worsen as the novel progresses.

Crux doesn’t hold back in its depiction of gritty, terrifying real life—but ultimately it leaves us on a note of, if not hope, possibility.

Crux releases February 5th 2026 from Fig Tree, Penguin General.

Image courtesy of Penguin UK.