By Film Editor ESMÉ FENICK.

Every December, the classic Christmas films start doing the rounds again, soaked in nostalgia. Home Alone, It’s a Wonderful Life, The Grinch – stories we know by heart at this point. They return with a comforting level of festivity. But let’s be honest, watching the same films every year comes with a certain monotony.

However much I love these films, the tradition starts to feel like a chore. So, as a film lover, I’ve put together a list of some of my favourite non-conventional Christmas films. These are films that, thematically, have nothing to do with Christmas. The season just sits subtly in the background, and that’s exactly why they work.

Think of this as an alternative Christmas watchlist, a way to break up the festive monotony and watch something a little different over the holiday break.

The Apartment, Billy Wilder 1960

Billy Wilder’s 1960s classic, set in the time period of Christmas and New Year’s, offers a satirical take on corporate America and the scandalous lives of unfaithful insurance brokers.

They use the Manhattan bachelor apartment of our good-natured, awkward protagonist C.C. Baxter (Jack Lemmon), as a refuge for their affairs. Beneath the comedy sits an undertone of corruption and melancholy that makes the film feel ahead of its time and refreshingly honest.

The Apartment presents a boozy, imperfect version of the Christmas season—one far removed from cosy family gatherings. Wilder’s Christmas is untraditional, breaking away from the idealised and protected nuclear family to highlight the loneliness and messiness that comes with the season. It is a reminder that Christmas isn’t always perfect, and neither are we.

Despite its dark undertones—an attempted suicide and a deeply unglamorous spaghetti-straining scene involving a tennis racket—the film wraps up neatly, like a present. Its ending is beautifully restrained and heart-warming, without feeling overly sentimental. Watch it if you’re craving a classic, or if you want a reminder that humans are messy, even during Christmas.

Eyes Wide Shut, Stanley Kubrick 1999

Kubrick’s final work, Eyes Wide Shut, stands as the ultimate counter-Christmas film. Set during a season associated with celebration and indulgence, the film explores what happens when these pleasures are taken to the extreme.

Christmas décor floods the film’s visuals. As Michael Koresky describes, “Christmas peeks from every corner of practically every scene, with trees both skeletal and verdant bearing twinkling colored lights; yet no one makes mention of Christmas other than to remind each other of the shopping that needs to be done.”

At its core, the film is a study of marital insecurity. Bill and Alice Hardford (Tom Cruise and Nicole Kidman) initially embody the illusion of middle-class, nuclear stability. This image collapses after Alice confesses her suppressed sexual desires. Bill’s pride is wounded, and he becomes fixated with pursuing his own sexual encounters. This obsession lands him in the underworld of New York’s elite. His night culminates in a nightmarish vision of masked, satanic ritualised sex. It is an environment defined by systematic abuse of power, particularly over women—the Marquis de Sade, the Machiavelli, the Epstein of it all—and a disturbing and eerie depiction of how wealth grants immunity and desire becomes a form of perverse control. With such dark themes, the question arises: why situate the story during Christmas?

Often read as subversive and by some as an attack on Christian values, Kubrick’s festive setting is not coincidental but essential. Christmas becomes a symbol of class performance and consumerist ritual. Sex and consumption are consistently intertwined, with transactions replacing intimacy. In this sense, Kubrick is not undermining Christmas but rather stripping back its glittery mask to expose the ethical emptiness beneath. If you’re in the mood for a Christmas movie served with a side of existential dread, Eyes Wide Shut is the perfect antidote to Hallmark cheer.

Tangerine, Sean Baker 2015

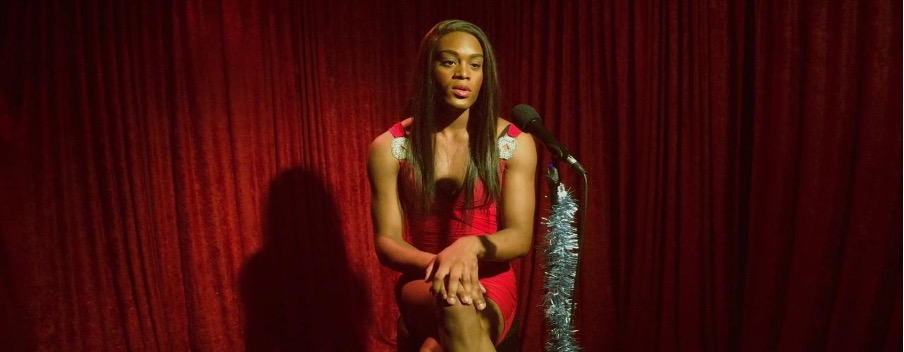

Set on Christmas Eve in 2010s Los Angeles, Tangerine rejects the idea of a cosy festive film immediately. Bathed in the harsh Californian sun and blasted with hyper-saturated colours, West Hollywood becomes the backdrop for anything but a white Christmas. Rather than snow, there’s heat, concrete and chaos. The film follows two transgender sex workers over the course of a single day on their mission of revenge. Shot entirely on an iPhone 5, Tangerine feels raw and intimate, situating it within the world of modern American neo-realism.

Instead of selling us the glamorised LA fantasy, Baker exposes it as a city that is unforgiving and hostile towards those living on its margins. The city is seen through donut shops, dodgy street corners and a run-down motel. Much like the previous two films mentioned, Tangerine quietly dismantles the traditional nuclear family. Christmas is not always kind to those without a conventional family. For many queer people, especially those rejected by their homes, the seasons can feel isolating rather than joyful. The film speaks to this reality directly, offering chosen families as something imperfect but vital in these times.

The subplot involving an Armenian taxi driver (Karren Karagulian) also breaks away from convention. Despite being a husband and father, he is emotionally adrift. His awkward and complicated involvement with the sex workers blurs the lines between desire and belonging.

Everyone in Tangerine is flawed and somehow refreshingly likeable. The film is chaotic and emotionally raw. It is a story about connection in a city built on alienation. Baker’s version of Christmas is far from polished and if you are after a queer, unconventional Christmas, this is the film for you.

Phantom Thread, Paul Thomas Anderson 2017

Set in the fashion world of 1950s London, Phantom Thread is a feast for the senses—and surprisingly, a perfect holiday watch. Reynolds Woodcock (Daniel Day-Lewis) lives a refined, regimented life. His meticulous routines define both his craft and personal world, often fueled by the women he finds as muses. His order is upended when Alma (Vicky Krieps), a young waitress with quiet charm, enters his life. Their romance is intricate and sometimes unsettling—a masterclass in how love can thrive in complexity.

Their relationship is delicate. An intoxicating dance between submission and domination. It’s deeply human, at once romantic and perverse, exploring the strange lengths we go to for love. A pivotal New Year’s Eve scene captures this perfectly: Alma wants to go dancing; Reynolds prefers the comfort of home.

Visually, the film is exquisite. Every garment sewn, every omelette prepared – it turns the material world into a part of its romance. Anderson transforms fashion, food and romance into a complete sensorial experience. Phantom Thread presents an utterly captivating love story set in a world so mesmerising, you’ll wish you could spend Christmas in 1950s London eternally.