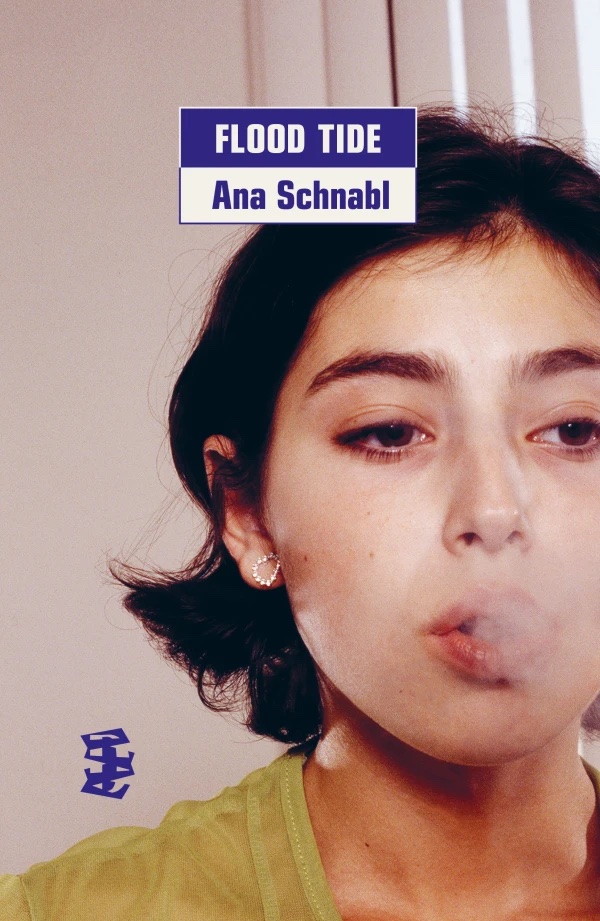

Ana Schnabl is a Slovene novelist, editor and critic. Her third novel, September, was awarded the Kresnik Prize in 2025. Ana is also a journalist, and a columnist for the Guardian. Her 2022 novel Flood Tide was released in English in October.

Co-Editor-in-Chief IRINE TENEISHVILI talks with Ana about manipulating language, structuring a retreat into the intimate and cerebral, and the negotiation of the self in a region, in her novel Flood Tide.

Irine Teneishvili: My first question is about smoking—I would say smoking has such narrative significance in Flood Tide and I wanted to ask, what does it represent for your characters? Is it one specific instinct, or is it one tool or mode of revelation for different characters?

Ana Schnabl: OK, first of all I am an avid smoker myself, so to me it is a thinking device. It helps me think. So I kind of transported this to the main character Dunja, who’s also a pot addict, of course. So all the cigarettes and the pot-smoking she does is a way to first of all find relief, and to — this is what she believes — think better, think deeper, and take time for herself, somehow. It’s the wrong way to perform self-care. But in terms of the narrative itself, it’s a device— I don’t know if you’re a smoker, but we smokers tend to pause, to smoke. At least I do. I never smoke when I work, I very rarely smoke when I write, but I do pause because I feel cigarettes help me structure my thoughts. With Dunja, as you saw, of course, her thoughts are not very structured, while smoking, but she believes that they are, that it’s helping.

IT: You mention performance and smoking — I remember the opening sequence when Dunja’s brother is smoking and she’s looking up at him on the balcony and is struck by moments where he looks more masculine because he is smoking. Do you think that there is an element of performing of the self when smoking, of posturing?

AS: Yes it is, it is. And I guess if you’re socially awkward, which a lot of people are, to some extent, it helps to strike a pose, to be more present in your body, because the majority of us don’t know what to do with our hands when we’re in social situations. So if you have this mediator, a cigarette, it helps you choreograph your hands, choreograph your body in space. And also, it’s a way to produce some contact with others, you know?

IT: That’s really interesting. I wanted to ask about an article you wrote a while ago. You spoke about the expectation of you, and generally writers from the Balkans, to write on tragedy specific to your country’s history. You described a process of “self-exoticising”, or a kind of othering of the self, that is necessitated by writing that positions tragedy as being specific to a region. Do you think that Flood Tide is an escape from that? Dunja says at one point that “being in love really is a kind of trauma” — is the exploration of these universal traumas deliberate?

AS: It is, to a certain extent. While I was writing it, I didn’t think about it that way, because I wrote Flood Tide during the pandemic, so in 2020, when I was perhaps a little less aware of my position as an author in the international space. But after that, my career kind of had its momentum, and I realised what was expected of me, as Slovene, as a person from the Balkans, what I should write about. When I wrote that article for the Guardian, it was a revision of my thinking. I hadn’t been aware that this is what I was thinking when I was writing Flood Tide. I’ve never been interested in mythologising our region, or the people that live here, it’s just something I find very problematic. I’m sure you know — your heritage is Georgian — people have certain prejudices about the region you come from. If they know where it is, of course!

IT: Yes, definitely.

AS: And Flood Tide is a relief, a step away from this, because it’s an intimate story, and it’s also a story about writing itself, about literature itself, so it tends towards the more universal.

IT: So, you might lean away from centering historical specificity, or focusing on the trauma of a nation, but I think that definitely Flood Tide plays with regional and natural specificity in a way which exposes the traumas of the individual, and the individual experience. To be more precise, what would you say is the significance of the Slovenian coast, and coastlines, as a literary setting in Flood Tide, and more broadly in your writing?

AS: It’s interesting you bring this up, because I’ve never been asked this question, even in Slovenia, where of course people are more acquainted with what the Slovene coast is like. The undercurrent of Flood Tide is the story of what the transition from socialism to capitalism did to the Slovene coast. In Yugoslavia this was a very developed region, with lots of very proper, quality tourism. Now, it’s become one of those monocultural spaces that you see all over the Adriatic coast, and even in the Mediterranean. It’s become a non-place, somehow. This is one of the main critiques of Flood Tide, and the significance of the setting. It begins in the 90s, when the effects of the transition were not as pronounced, and when Dunja visits, we are in 2019, so all these processes have already peaked.

IT: And leading on from that, I wondered if you have any particular writers or works that have influenced you in their configuration of the relationship between water and coastlines, and narrative?

AS: No, actually, what’s really interesting is, I’ve never considered myself as an author who is very interested in spaces, or even nature. But Flood Tide is a very intimate expression of what I feel about the Slovene coast, because I’ve spent so much time there, and I saw all these processes and changes up close. So no, I prefer to read, lately, kind of nasty fiction. I never search for anything related to the Adriatic specifically.

IT: I also wanted to ask about the epigraph to Flood Tide, which is a reworking of T. S. Eliot’s “April is the cruellest month”, and you write, “August, August is the cruellest month”. I thought the way that you presented sunlight was really interesting, and similar in a way to The Waste Land, where you have these subversions of nature — how would you say that all the sunlight and oppressive summer heat function, either symbolically or as a force driving narrative, in Flood Tide?

AS: I think you answered in the question — it IS oppressive. I always considered August on the Slovene coast, as a very, very sneaky month with its light, because it’s a kind of veining light, a disappearing kind of light. You really feel the coming of autumn. It’s still very hot, everything is very intense and very pronounced, and I find these circumstances to be oppressive in themselves. Bodies can’t relax, can’t breathe. We don’t see that well because— if you’ve ever been to the Adriatic, you’ll notice that August has this shimmering, even foggy quality to the air. So it’s just … not that pleasant. And also, the epigraph is a reference to one of my favourite novels, from when I was a teenager—The Light in August, [by William Faulkner], which is also an oppressive story, a story of searching, and posits that the light, in August, is searching, but in a destructive way.

IT: What was the process like, of writing the novel? You said it was during the pandemic, how did that change things?

AS: Very easy, because it was during the pandemic. I was one of those lucky bastards who was able to work from home. I call myself a “warmonger” because I made a lot of money during the pandemic, working internationally also. I was actually in residencies during the pandemic, which was strange, but I could travel. To Switzerland, Croatia, Italy. It was easy! People often ask me if it was difficult to find this “style” of Flood Tide, but I just find it so natural. Even though I was quite relaxed during the pandemic, I was quite neurotic, and this neuroticism translated very easily to the style.

IT: In your writing, would you say that you prefer to devote more narrative time and space to characterisation rather than developing plot?

AS: It really depends on the work. I’m very versatile in my approaches. I am more on the character side, I lean towards this. I am not that interested in plot, maybe only in film, where I need very strong narrative to not fall asleep, basically. But with reading and writing, I really don’t care what happens, but I do care about the people. But that can change, for instance the novel I am writing now is more topical, more theme-driven, more plot-driven, than character driven.

IT: You bring up film— are there any films which may have influenced your writing generally?

AS: I have terrible taste! I have the taste of a male boomer. I like films which depict very sad, miserable men. I like detective stuff, cop stuff, mob movies. One of my favourite films is Barry Lyndon, by Kubrick. I’m kind of ashamed of this, sometimes, because it’s not in the current vibe, of what a woman should like. But in what I relate to, I always lean a little towards the violent parts of the human.

IT: I wanted to ask about interactions between the feminine and masculine in the novel. There’s a description of Dunja as a young girl being affected by gravitation that is “not earthly, but moonly, maybe”. I was wondering if you could talk about gendered environments — if there are any, a connection between the feminine and the moon, obviously how that plays into tides, and perhaps how this interacts with the masculine in the novel.

AS: The moon device itself was not gendered, to me, more so connected to the phenomenon of the tide, to the gravitational pull of the moon. When it comes to gender, in Flood Tide, you’ve probably noticed there is some prejudice against males, in the narrative. They are depicted as somehow weaker, in the sense that they are not able to inhabit themselves fully. They are not brave enough to inhabit themselves fully. And it’s not just about Kristijan’s homosexuality, but also Drazen, we don’t get to know that much, but he’s a very ambivalent, kind of a nasty character, and this nastiness of course presupposes some lie, and an inability to inhabit his character, basically. Whilst the women, despite their limitations, and their internal violence, are somehow more in touch with their ambivalence, the ambivalence of their identities. Even with Katy, who seems to be a very sadly pragmatic person — sad and pragmatic, pragmatically sad — she’s okay with the choices she makes, somehow. Not really at peace, but she can endure. It’s not a feminist novel, it’s actually more a novel about prejudice against men.

IT: To continue on this theme of the tide, I was interested in whether this motif of rising and falling was connected to a linguistic motif I picked up on, of the movement between dilation and compression, or focusing outward and inward, for example where you talk about “centres and provinces”, with Dunja being the centre. How do those two things interact?

AS: I will start very materially. When I gave this novel its title, I referred to the fact that Drazen died on the beach. But it was also a reference to the style — a very intense rising, very vulgar and nasty, and then it becomes more poetic. It has these oscillations. It’s a depiction of how the mind moves. It moves— I mean, you’re human, you know how it moves. It accelerates, stops, then becomes something else. As you said, it compresses, decompresses, compresses, decompresses. So, yes, the tide is much more than just a natural phenomenon in this book.

IT: I found the narration in this novel really intriguing, especially how it plays with language. Often the narration diverts to talk about etymology or meanings of words, and it constructs Dunja’s character in this way, in real-time. And there’s a couple of moments where we see sarcastic remarks where Dunja’s cruelty is pointed out, for example at one point the narrator says “What a way Dunja had with words!” when she is commenting on a child being overweight. How would you describe your exploration of the function of language itself in the narration? Is it sometimes violent in its use for characterisation?

AS: You asked before about if I care about characters or plot: the thing I care most about is language. I think it derives from the fact that I am a failed musician. I only have one very poor musical talent, I can sing a bit. So I never became what I wished to become. Language is kind of a proxy for this failed ambition, failed career. I really use it as a sound. I think the English translation depicts this very well, but in Slovene it’s even more pronounced, it’s a lot about how things sound, more than what they mean. Dunja, of course, as a writer, and because she’s a proxy for my failed ambition, she cares about this a little bit too much, a little bit more than she does about the integrity of the people she cares about, and this really shows in the scene with Duska, who has stopped losing weight and is now empty. In Slovene, the word for losing weight means “to get worse”. I played with this a lot. There are also other instances in which I, as an author, play with this, and Dunja plays with this, in her mind. I think it’s also because she’s a very incorrect person, very aware of her cruelty, even though she strives to be pure, but really can’t be. She uses language, and the etymology of language, to maybe be forgiven, for her cruelly. If it is in the language, then that makes it ok.

IT: I wonder how you feel about translation, in that context. For a work that’s so concerned with the structures and intricacies of language, does translation complicate that?

AS: It does, a little bit, but I think Rawley [Grau, the translator], did an amazing job, I mean he really did a lot of heavy lifting. I don’t know how he survived and why he doesn’t hate me yet. But of course certain linguistic inside jokes are lost, always. But he strived to find others at other points. We couldn’t tell it all, at the specific times in the novel, so we made a common decision to try to salvage this inside joke realm at other points. What’s amazing is that at a certain point, after six months of doing this work, he came to think as I think. So he came up with suggestions of how to remain as jokey as Dunja is in Slovene. That’s a true talent.

IT: Yes, of course, that’s so impressive. And I just have one final, very off-topic question. Is there a book you’re currently recommending?

AS: Yes! I have it here. Rejection by Tony Tulathimutte. He was nominated for the National Book Award. I discovered his work because I know his translator, Vincenzo Latronico, the big star at the moment. Rejection is a — it’s so nasty! I love it. It’s a collection of short stories that function as a novel, because all of the characters that are depicted are related. It’s about loneliness, and heterosexual relationships in the age of “supposed” consent, and under capitalism and the internet, and it’s amazing.

Flood Tide was released through Divided Publishing on October 27th, 2025. Image courtesy of Divided Publishing.