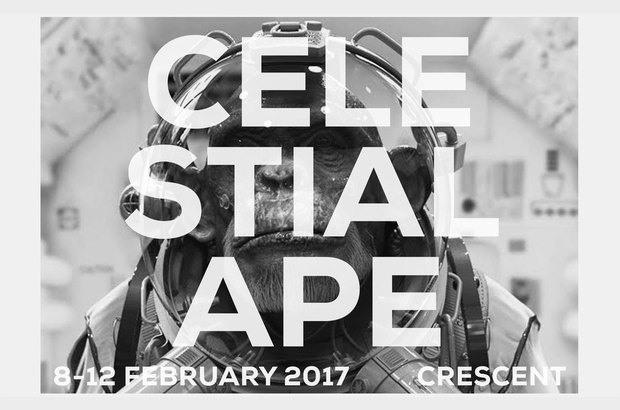

SUSANNAH BAIN interviews JAMES KING, the writer behind Celestial Ape at VAULT Festival.

I call James King on Saturday afternoon, four days before his new play, Celestial Ape, opens. A friendly, if slightly rushed, voice picks up. He is in rehearsals and I wait as he leaves the studio space. From the promotional material, Celestial Ape looks like an eclectic production – an exciting mixture of wide-ranging dramatic elements thrown together to express a terrifying political climate overshadowed by fears of a potential ‘apocalypse’.

I am worried about trivialising: 2016 was a painful year in too many ways, and I am worried King will ridicule it without delving into its political and emotional implications as the best theatre can do. We start with the inspirations behind the production: he tells me that he had for a long time been planning a short story about a Soviet space monkey. He is quick to point out that although technically the Soviets sent dogs into space – and it was only later that the US sent monkeys – monkeys seemed to work more neatly as a parallel with humanity. His ‘partner in crime’, James Carney, with whom he wrote and directed a short film called My Dead Body last year, was at the same time succumbing to a developing obsession with puppetry. The two ideas were squashed together: ‘the genesis being a show involving a puppet of a Soviet space monkey witnessing the nuclear apocalypse while orbiting the earth in a small satellite.’ Such a strange match-up sounds intriguing, but I’m still afraid that puppetry and space monkeys are only the two fascinations of two (clearly fascinating) lead creatives, spliced together with some political depth added to sell.

King quickly cuts my worries short, ‘as the events of 2016 began to rapidly unravel I had the idea of doing this almost resilient apocalyptic variety show.’ He explains how deeply the events impacted him personally, before universalising: ‘People feel like pawns being toyed with by these unstoppable and kind of unknowable figures. There are so many things happening that we are utterly powerless to change, and it feels like the world’s ending … Rather than wallowing in despair (which I did spend most of 2016 doing), I wanted to create this idea of a ‘stoic variety show’, where we kind of said “fuck you” to everything. Let’s stop tearing our hair out and just accept that things are crazy and have fun with that.’

King’s enthusiasm is obvious: these are issues that seem to have impacted him profoundly and it seems clear it is through absurdity that he finds he can express a personal response. His passion is also clear in his ability to talk at length. He is a storyteller. We go on to discuss the cinematic influences on the play. King’s day job is with Artificial Eye as a film distributor, and much of the production team are involved in the industry. He tells me the films of Tarkovsky, particularly Ivan’s Childhood, have greatly influenced Celestial Ape: the onstage space-monkey echoes several iconic moments of cinematic imagery. Vertov’s Enthusiasm also played a large role, and, letting his inner film-fanboy out, with this explanation comes an extensive history lesson of Vertov’s film and influence on the production. That said, the main cinematic foil is La La Land: there is a duet number in the first half of the play which references the recent cinematic sensation, along with a sketch investigating quite why he hates it so much – contrary to its general adoring reception. He got in some trouble, he tells me, for describing it as ‘A Hitler Youth Musical Dream, directed by Ayn Rand’, with ‘quirky Caucasian people Jazz-plaining’.

The La La Land sketch is buoyed by a bizarre collage of skits and scenes. James tells me that it is only in the second half that the journey of our celestial ape – from the Cameroon jungle to cruising amongst the stars – is staged. The first half, in contrast, is an ‘apocalyptic variety show’, with songs and comedy sketches, and a TED talk presentation about the correlations of Britney Spears’s collective videography and the collapse of Late Capitalism. Performers such as journalist Simran Hans, James Carney, Tom Rosenthal and the animator Harry Partridge contribute – two of the latter’s animations having thematic and aesthetic resonances with the show. All through our conversation, King speaks about his collaborators with touching warmth: ‘It was a case of reaching out to everyone we knew and putting in as many favours as possible to create this slightly bonkers and probably ill-conceived show that hopefully some people can enjoy.’ I can’t help but think that this collaborative process in particular speaks volumes, not just in terms of having a variety of means to communicate the show’s message(s), but also in that it gives a solidarity to what is being said. This is at the crux of the play – it isn’t his own personal pursuit of quirkiness, as it initially seemed, rather it is all those involved sharing and despairing together, yet creating something to express and examine those feelings.

Theatre can and must relate back to its broader cultural context. It must bite back, take the piss out of it, cry over it, sing over it. But more importantly, it must be a forum – a place in which audiences share in what they are seeing. ‘Because the play itself is trying to remind us about what we have in common. We need to all calm down, have a laugh, and try to find a way to get through this without destroying each other – because the alternative is oblivion.’

Celestial Ape is playing at the VAULT Festival in London from 8th to 12th February. Find tickets and more information here. See our review later in the week.