Following the publication of Sleeveless and Artless, Natasha Stagg has been recognised as the figurehead of a certain literary scene centred in Semiotext(e)’s New York. She is a representative of the contemporary novelist-journalist-critic, a kind of Didion for her time. In much of her writing Stagg serves as part raconteur-part reporter, offering keen observations of the metropolitan art world that frequently lapse into gossiping anecdotes. Grand Rapids is her first book following the “Less”’s, and is a novel proper inasmuch as it follows a singular, fictional narrative.

Tess, protagonist, is a fifteen year-old girl who has lost her mother to an anonymous cancer. Before her death, the two had moved to the eponymous Grand Rapids, Michigan following her parents’ divorce in order to be closer to her mother’s sister, Norma. Tess’ father is out of the picture, an unquestionable fact: “I don’t think I even knew his email address, if he had one”. Once her mother dies, she is somewhat awkwardly inaugurated into her aunt’s family, who are cheery, well-meaning people, but in a way that seems absurd when approached via Tess, taciturn from grief and adolescence.

Tess works in a care home for the elderly and enjoys making half-sentimental observations on the infantilising effects of age on the body. As we first encounter the novel, she is watching reality television and spots an older man, “the politician”, with whom she has been nurturing an epistolary relationship via online messengers. She is not particularly moved by seeing a televised image of this man. It is noted more as a sort of tick-the-box milestone, “the first time a person I personally knew was on television”. There are no traces of first-love throes, neither towards the politician nor later boyfriends. The narrative begins prematurely cynical and without wide-eyed innocence. It is, in fact, rather unsentimental throughout, despite being somewhat “diary-of-a-teenage-girl” in genre. Tess enjoys car rides and gigs with older boys, taking drugs, and her quasi-lesbian relationship with her best friend Candy—and in that order. The teenage girl is reimagined away from a pained, inward-looking subjectivity. Stagg’s girl is more interested in sitting in the backseat, listening to those up front.

Grand Rapids is, essentially, a half-fulfilled bildungsroman. It is interested in a girl habituating to the trials of late adolescence, becoming known to men, traversing the difficulties of female friendships, moving from place to place. “The way women grow up is into each other”, the protagonist tells us retrospectively. Stagg’s narrative does not present a linear development of Tess, it does not terminate on her meeting any great expectations. A retrospective present tense and the present-tense voice of adult Tess that reoccurs throughout is where the text reaches the heights of its coming-of-age wisdom. It blurs temporal distinctions, and undermines the gravity of events as they occur. The outcome of “Candy’s life” is laid out before the reader is really acquainted with her as a character. Reading Grand Rapids is not dissimilar from flicking through a teenage diary, paying little heed to chronology, the reading act interspersed with moments of grown-up contemplation. Tess, indeed, comes back to reading her late mother’s teenage diary throughout her time in Grand Rapids. It lies beneath the text as a spectral sub-narrative against which Tess compares her experiences and insights. She finds more similarity than difference, developing into rather than growing up.

It is set in the urban space, although one which is apart from that sense of importance and permanence evoked by novels in New York or Los Angeles. It’s not quite a narrative of the small-town girl either. Grand Rapids, as a place name, has a majestic ring to it, suggesting an environment of hierarchy and fast-pace. Although the reality of the place is underwhelming, a city of one coffee shop and a half-arsed garage band scene, it has a flesh-and-blood vitality that mirrors the restlessness of its teenaged inhabitants and seduces with the prospect of leaving for something greater. If Paris is a woman, Grand Rapids is a teenage boy. “Dirt City”, it is called colloquially by Tess and Candy’s romantic half-interests, Mickey, Stephen and Robert. It is a first draft of a city that takes root, but does not grow past a middling feeling of wasting time.

The earthbound idleness that Tess experiences at Grand Rapids is relieved by representations of the water that runs through it, a reminder of high velocity and direction. At a later point in the novel, once experience has begun to settle into insight, Tess watches the river, and remarks its “foam snaking and dispersing at a pace that mocked the waddling crowd”. She is with Mickey, a junky-adjacent older boy who she has been nervously sleeping with for the previous half of the novel. As her attention turns from the river to Mickey, she notices that “his face was smaller than I’d remembered”. Stagg’s tone is characteristically distant throughout, but here, as Tess meets with the grandeur of the wider world, the text is cemented into a moment where the young girl develops a certain insight, a vision of something elsewhere.

The novel develops an interest in cleanliness. Although certainly not hygienic in many of her bedroom-filth environments, Tess is drawn to clean cuts. The slit of river that runs through Grand Rapids promises a spiritual cleansing. The possibility of detoxification thrills Tess. The sharp pain of her self-inflicted burns as she sits on the cold linoleum bathroom floor is interpreted as clarity, a respite from the diseased textures of her external world: a bedroom that “felt like a mouth” and car backseats “spewing yellow foam”. Narrational temporal jumps try to form a truth out of young Tess’ intoxicated memories. “I’ve intentionally dissolved parts of my brain with chemical shards and liquids, distressing existence’s fabrics each time”. The cool retrospective voice speaks like a chemist recalling her observations of the effects of a substance reacting against flesh.

Young Tess gets high off cough syrup and writes its effects in her diary like a child playing doctor, although her degree of insight is debatable. “I wrote in my diary that I was finally happy, which was sad”. Inward observation in Grand Rapids is, except for in its flashes of present-tense adulthood, generally murky. But Stagg’s characteristically aloof register excels in Tess’s quiet observation. While the interior self is dissected and imbalanced, the observable world of people offers clarity and a foundation for the text’s coming-of-age.

It is somewhat radical to show the development of the teenaged mind completely away from coddling self-help or soul-searching. Stagg’s protagonist is barely a participant in much of the dialogue. It does justice to the “dumb” young girl that listens to the boys and watches the gobbier girls in awe, absorbing much of their turns of phrases and views so that she is not totally peripheral, but involved in her quietness. Grand Rapids is a bildungsroman of a low-voiced adolescence which grows in seeing and listening. It’s not passivity exactly, but a tumultuous, eager collection of input.

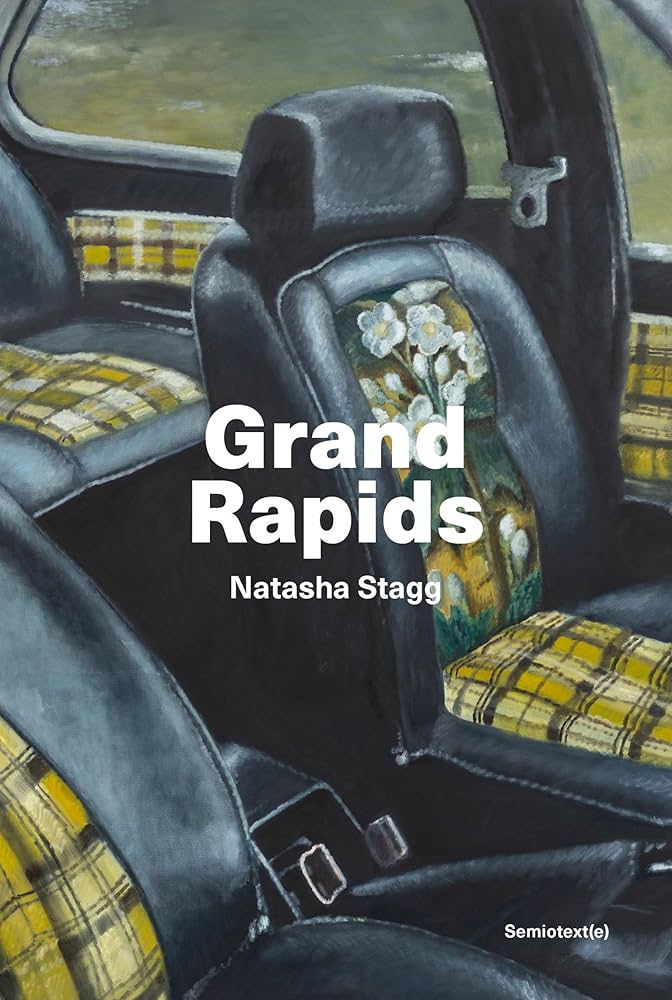

Grand Rapids is available through Semiotext(e). Cover art by Issy Wood.