Art & Design Editor SARAH LOUISE reviews two standout solo presentations at Frieze London: Emma Rose Schwartz at Brunette Coleman and Xingzi Gu at Gallery Vacancy.

Frieze is less a quiet stroll through artwork than a carnival of excitement and expectation. Lights glint on polished frames, seas of people wander through rows of carefully installed booths, champagne flutes tilt, and conversations dip into curiosity and rise into questions. Yet behind the surface flashes and chatter there are pockets of stillness where art lingers and breathes. It is in those moments—when the crowd parts and a booth becomes a room of quiet—that two solo presentations in the ‘Focus’ section stand out.

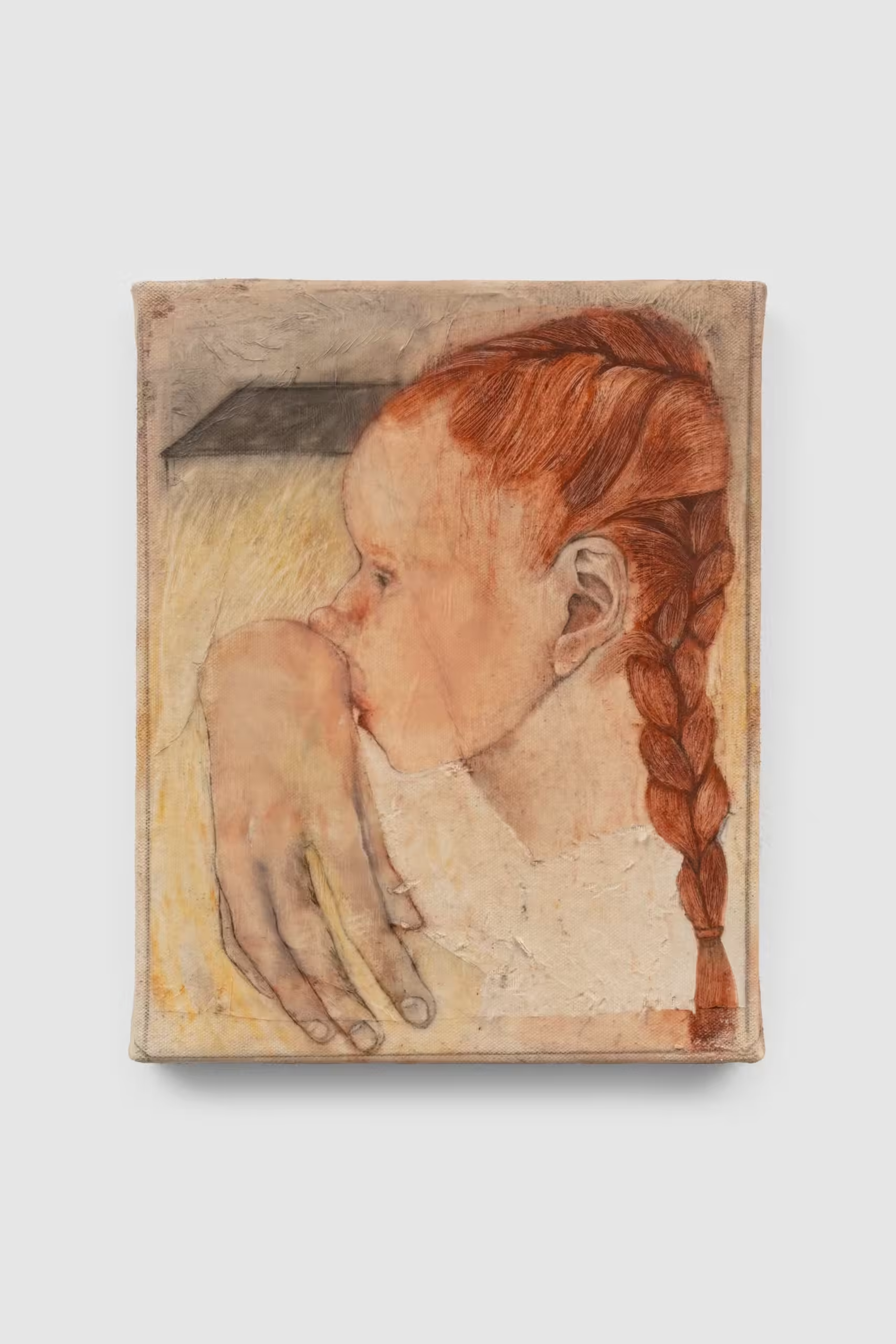

Stepping into Brunette Coleman’s booth, exhibiting the work of New York-based artist Emma Rose Schwartz, I feel as though I’ve entered a memory filtered through a dream of childhood. Schwartz’s paintings evoke a world both familiar and off-kilter, and here, in this small space, that tension is made vivid. Her palette is muted but intimate: linen whites, charcoal, rusty browns, soft reds, and a tinge of yellow. The works have a weathered quality that feels nostalgic, yet fresh.

Observing Trundle (Front) and Trundle (Back), I find myself suspended between waking and dreaming. The two paintings depict the same scene from different perspectives—three young auburn-haired girls lying side by side. The figures are almost identical, but not quite, like afterimages. Schwartz has remarked that they each exemplify “fractals” of herself. In Trundle (Front) I am met with the intense and almost mischievous stare of one of Schwartz’s protagonists. The depth of her gaze contains a strange composure that draws me closer even as it unsettles me. Her eyes record the invisible labour of existing as a self under scrutiny—the way a body learns to fold and unfold under the pressure of being watched.

The rest of the canvases, too, display auburn-haired girls that appear as almost ghostly figures. In Suns up, a girl lies on the ground in a makeshift bed of cushions, a worn-out leather jacket strewn over her body as if it were a duvet. She appears small, as if she might disappear into her domestic surroundings, yet at the same time large with her disproportionately long legs. Similarly, in Equal Tilt, a girl wipes her nose on the back of her hand, which appears to be the same size as her head. These distortions are not grotesque; instead, the effect is both defiant and vulnerable. It recalls the way adolescence feels from inside the body—the sense of being slightly misaligned with one’s own form, growing faster in spirit than one’s limbs can follow. The girl’s hand might belong as much to her future self as to the child she once was. In this way, the body parts operate in their own temporal rhythm, suggesting that identity here is not a single moment but a chorus of overlapping selves.

The notion of waking and sleeping, of sleep mimicking death and waking as revival, infuses the work with a subtle urgency and nostalgia. The threshold of consciousness becomes the threshold of identity. The domestic interior is the dreamscape, and through the innocent figures, Schwartz captures an uncomfortable and tender stage of adolescence that bleeds into the present. As spectators, her work asks us to slow down, to lean in, to contemplate what we carry and what we leave behind.

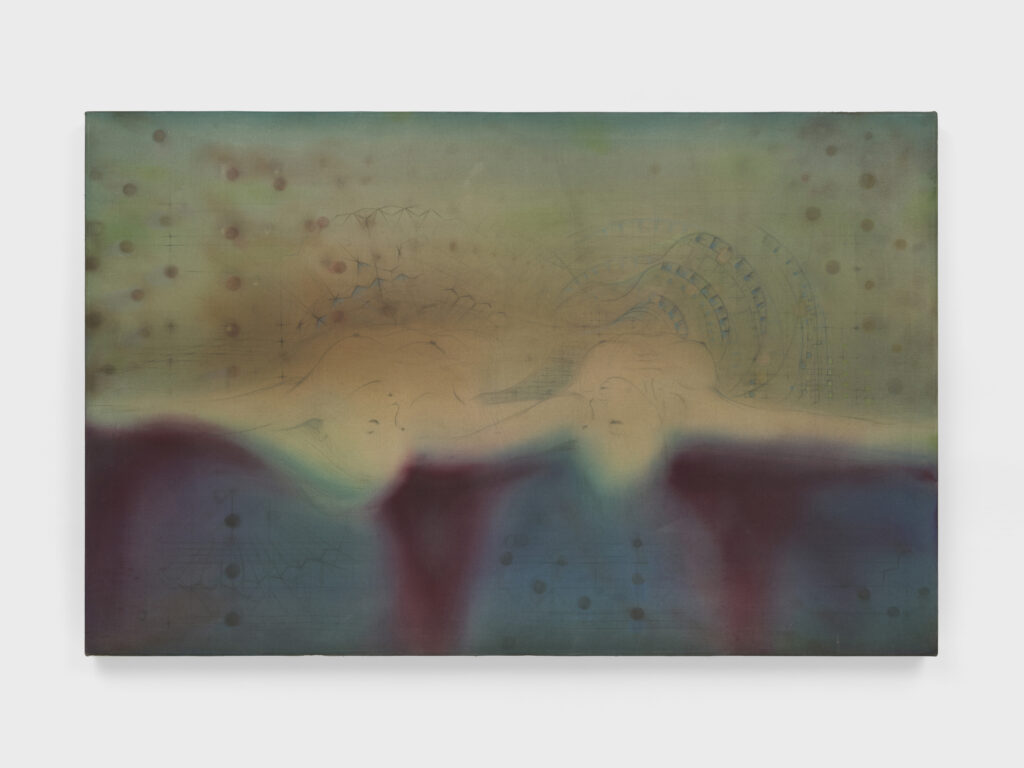

Weaving my way once more through a crowd of trench coats, Tabis, and Loewe bags, I move around the tent like a particle inside a glimmering, overstimulated organism. It is in the midst of trying to distract myself from my state of fatigue and dehydration that Gallery Vacancy’s booth glints in the distance like a mirage. Here, Brooklyn-based artist Xingzi Gu’s exhibition A Half-Dream is a quieter, more ethereal register—a pocket of condensation in the fair’s dry air. The hush that greets me isn’t silence exactly; it is a kind of density—the feeling of moisture on the lens, a soft-focus memory half-remembered. The gallery notes that Gu’s paintings are a mix of oil and acrylic, and they use a traditional Chinese brush-painting technique to depict the misty landscapes and figures that inhabit them.

Gu’s work engages with dislocation and belonging—the notion of foreignness, of cultural drift, and of youth suspended between identities. As I observe the paintings around me, I notice that the dream here is less of a childhood home than of becoming: androgynous and fluid bodies, quiet gestures, and landscapes of longing. In Light Sleeper, two figures rest in a hammock surrounded by an idyllic landscape, their forms so delicately painted that they look as if they’re about to dissolve into air. It is as if Gu aims to not capture the moment itself but its emotional residue. The painting is scraped of excess, and what remains is essence—faint, trembling, alive. Dropping Needle holds a similar tension. In the foreground, a woman threads a needle, while another figure lingers in the doorway, plant in hand—a composition as much about the space between them as about either body. The colour palette is almost whispering: muted greens, bruised pinks, and light blues. Gu has spoken of their understanding of the body in relation to Eastern tradition, in which one focuses on the aura of a person rather than their anatomy. I find that in these paintings, too, emotion and energy become a mist of pigment, as the aura of the figures is prioritised over their flesh.

Gu’s work also lingers on adolescence and intimate moments that convey the tenderness of uncertainty and one’s loss of childish innocence. As my eyes glide over Landline, I am drawn to how their subjects are suspended between the clarity of youth and the opacity of adulthood. Here two figures lie side by side gazing at each other, naked from the waist up, tutus circling their hips. The painting feels cinematic in a quiet, elliptical way, like a film that begins halfway through a dream. Whilst scanning for edges and outlines that seem to keep dissolving, I realise that the experience of youth, memories, and dreams is much like standing before one of their canvases. To look at them is to feel time loosening its grip and slipping past my fingertips.

What unites these two presentations is their shared dwelling in liminality: the threshold between wake and sleep, memory and presence, adolescence and adulthood. Yet their approaches diverge beautifully. Schwartz builds from the inside out: her world is tactile, embodied, and insistently domestic. Her auburn-haired girls with their elongated limbs and oversized hands stretch against the limits of selfhood. Gu’s figures emerge from vapour, from the soft humidity of recollection. The dream is not the return home but the movement outwards. But together, in the buzz of the fair, they feel like twin invitations: to slow down and enter the dream-frame.

Featured image: Installation View, Brunette Coleman. Frieze London 2025. Courtesy of the gallery.