ALICIA DORAN and CAROLINA TANI review Charlie Porter’s new book, which takes the Bloomsbury group as focus and unpicks the language of clothing.

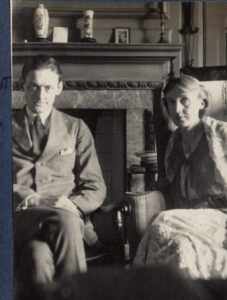

Charlie Porter at Charleston wearing homemade garments Photograph:© Sarah M. Lee

The intriguing title of Charlie Porter’s new book comes from a letter written to T S Eliot by Virginia Woolf, in an invitation to stay at Monk’s House, her home in East Sussex; ‘Please bring no clothes – we live in a state of the greatest simplicity’. She meant not to come naked, Porter explains, but that there would be no need for formal or ‘good’ clothing. But there is certainly a sense of undressing and baring all in the book; Porter spoke to us at Waterstones Gower Street of his intentions to ‘cut away the gossip and the myth’ that surrounds the Bloomsbury set and provide an intimate personal perspective through the study of their clothing. Although there are no surviving garments belonging to central figures like Woolf and Vanessa Bell, Porter presents us with a wealth of written and photographic material exposing complex and sometimes radical concepts of dress, charged with ambivalence, rebellion and creativity.

He devotes a chapter each to six Bloomsbury figures: Virginia Woolf, Vanessa Bell, Duncan Grant, EM Forster, John Maynard Keynes and Lady Ottoline Morrell. In the opening chapter, he describes Woolf’s fascination with ‘frock consciousness’; although self-describing as ‘badly dressed”’ her writing shows a critical understanding of the language of fashion. In Orlando, Woolf investigates the role of clothing in constructing gender identity, acknowledging the power of what we wear to ‘change our view of the world and the world’s view of us’. In Mrs Dalloway, Clarissa’s green party dress takes on layered symbolism; the dress mediates her inner self and her public-facing self, and its tearing and mending reflect her vulnerability and efforts of self-preservation. At a more biographical angle, Porter reveals the role clothing played in the Stephen sister’s sloughing off the restrictive conventionality of their Victorian upbringing with their move to 46 Gordon Square. Swapping corsets and seed pearls for unstructured and experimental garments signaled their freedom to become modern artists on their own terms.

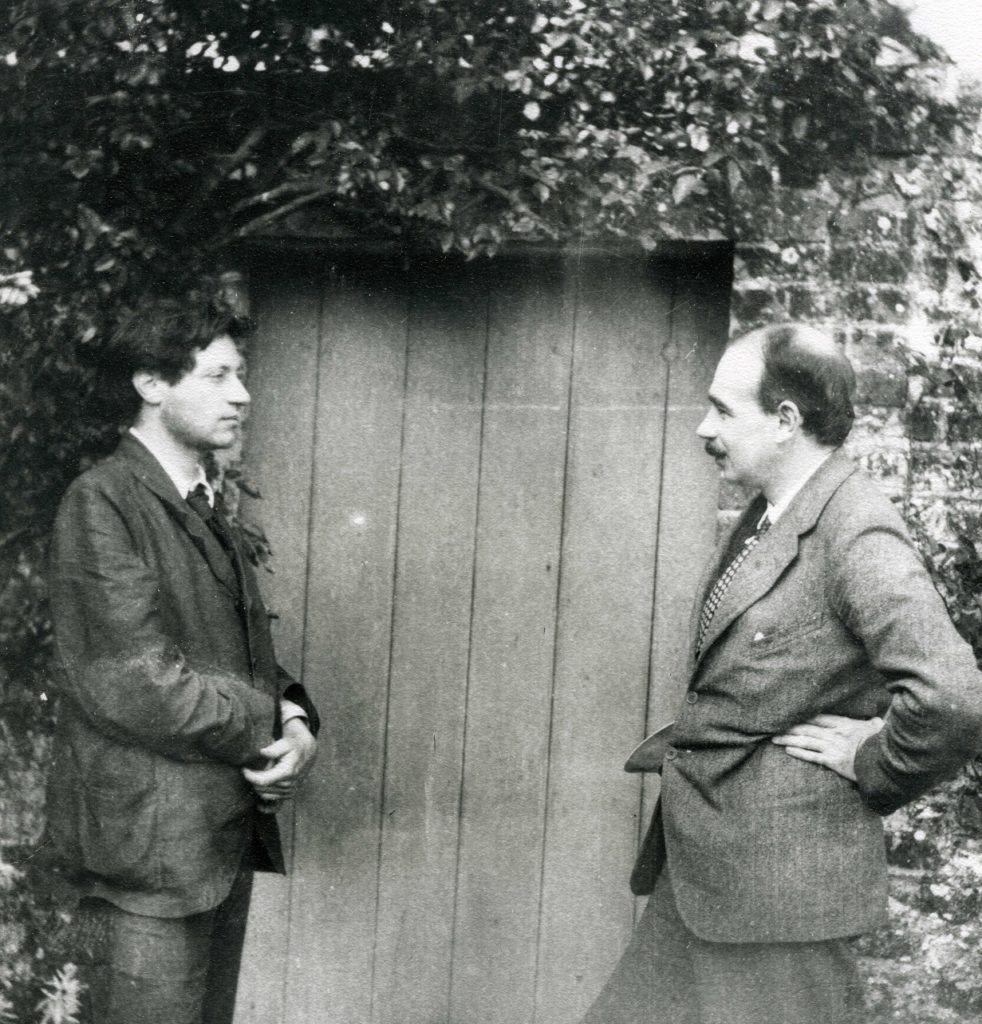

Porter has long been interested in menswear, and in the chapters on Grant, Keynes and Forster, he provides a deconstruction of the suit and its associations of authoritative, impenetrable masculinity. At the heart of Porter’s connection with these figures is queer identity, its expression and suppression; his chapter on Forster is a poignant exploration of the fear and discomfort that comes with navigating a straight-laced heteronormative world while he finds a more free and unabashed queer identity in the figure of Duncan Grant. Porter presents him not so much through the clothes he wore but rather how frequently he took them off. Sex also figures heavily in Keynes’ chapter, where we are reminded of the suit’s function as a signifier of power, or, as Porter puts it, ‘the thing men use to get what they want’.

Throughout the book, Porter insists that we should learn an ‘anti-fashion’ attitude from Bloomsbury’s sartorial philosophy, to ‘bring no clothes’ in our twenty-first century lives. The abstractness of this message becomes slightly confusing. One interpretation of the book’s title is to reject formality, to stop ‘dressing for dinner’ (or parties, or work?). Additionally, we might learn to tune in to ‘frock consciousness’, and to become more aware of how social differences and power structures are communicated through clothing. Social media’s recent fascination with ‘old money’ looks is an interesting example of how class is conceptualised through clothing, and how fashion perpetuates disparity. On the other hand, surely to ‘bring no clothes’ is to think very little about what we wear at all… It seems it was far more straightforward for the Bloomsbury group to truly subvert and transgress through clothing than it is for us; the rigidity of Victorian dress makes rebellion fairly simple. But here and now, after decades of development in fashion, innumerable countercultural movements whose radical looks eventually bleed into the mainstream (ie beatniks, punks, hippies, grunge), can an individual be truly anti-fashion? Can we ‘opt out’ of the industry that literally surrounds us and is a primary medium of identity culture?

Undoubtedly the most convincing of Porter’s propositions is the refreshing potential of making our own clothes. This activity is a refrain that comes back again and again all throughout the book. We are introduced to Vanessa Bell through her creations and we discover how they influenced the author himself. Porter goes in great depth about how making clothes impacted him. First, a way to deal with the grief of losing his mother and process his pain, as she was very fond of sewing herself. Later, a joy-inducing activity that expanded his view on fashion and became a true passion. At the launch, he sported a red frock coat and navy trousers that he had sewn himself.

When you make something, it becomes more than just an object, more than just clothes. Now it’s a creation, it holds meaning and has a history. This is not to say that Porter’s book suggests a radical switch to only hand-made garments. But, it does introduce the idea of separating ourselves from trends. When Bell started making her own clothes, it was symbolic of her being freed from her scarring girlhood and the rules that came with it. Maybe we can also adopt this act of liberation. Free ourselves from excess, but also from short-lived fads. It’s easier said than done, but it’s essential to consider how the decade we live in helps promote this activity. Making your clothes is in vogue. We watch enchanting videos of people knitting themselves a party top or a cozy sweater, upcycling a pair of jeans into a mini-skirt or sewing a whole dress from scrap fabric. During the talk, a girl in the audience shared how she is now making nearly all of her clothes, only relying on stores for knitwear and shoes. What a wonderful thing! The fashion world of today is overtaken by concepts of sustainability and hand-making.

Even if Porter’s readers don’t take the leap of hand sewing their own wardrobes, they might be encouraged to find more personal artistic joy in clothing, as well as remain aware of the implicit meanings and impacts of garments. Virginia Woolf wanted her guests to ‘bring no clothes’, to not feel constrained by society’s confining dressing norms, she wanted them to be themselves, nothing more and nothing less. Today, to write ‘bring no clothes’ at the end of a dinner invitation could mean, simply: ‘be authentic”’ Be critical of the status quo and harbour a sensitive understanding of clothes. See fashion as an open discussion and a universal language that is spoken around us at all times.

Alicia and Carolina caught Charlie Porter in conversation with menswear designer Steven Stokey-Daley at Waterstones, Gower Street on Wednesday, October 18th. Charlie Porter’s new book ‘Bring No Clothes: Bloomsbury and the Philosophy of Fashion’ is available now at Waterstones and most book stores.