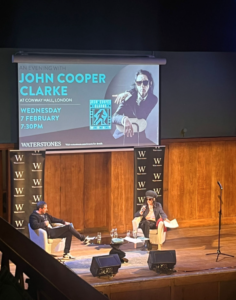

NATALIA MOSQUERA attends a talk with John Cooper Clarke, celebrating the release of his new poetry collection.

If you were walking down Red Lion Square on the evening of the 7th, it would be understandable to think that Conway Hall was a comedy club—such was the laughter erupting from London’s cultural landmark. Walk inside, and you will find the source to be a solitary, slight seventy-five-year-old in a suit. He looks like one of the three blind mice. He sounds ‘a bit like that fucking Liam Gallagher’. He performs like Alex Turner if Alex Turner was older and happier. He is a poet. Ladies and gentlemen, Dr John Cooper Clarke.

Cooper Clarke was at Conway Hall to promote his latest poetry collection, WHAT. As the evening’s delightfully disgruntled moderator Colin Murray revealed, the poet is not one for preparation:

“I was sent a landline and rang four days ago. He talked about daytime tv for fifteen minutes, hung up, then arrived twenty minutes ago and said, ‘I’m going to do a fucking set,’ …and here we are.”

Having witnessed the set, this makes an awful lot of sense. Cooper Clarke’s poetry, arguably more than most, relies on its musicality. He claims, ‘the main thing about poetry is that it should be phonetically pleasing.’ He was a staple of the 70s punk music scene, temporarily shacked up with Nico in the 80s, and inspired the aforementioned Arctic Monkeys frontman to adapt his poem ‘I Wanna Be Yours’ to skyrocketing success in the 2010s. Cooper Clarke has more live performance albums than poetry collections—seven to three—and his hero is Elvis. His poems are sonic tricks that make full use of rhyme, rhythm and alliteration, and when he reads them right, they launch out of his mouth with an almost rap-like quality. All of this is to say that when Cooper Clarke stood on that stage in Conway Hall reading from a font at least seven points too small, the stopping and starting was unsubtle.

‘In long pants, I feel overstyled. I look at a dog, I see a blind child. I look at a car, I see a planet defiled. Where the summertime is a burning hell, in a wound up, webbed up whereabouts, where the worried well dwell. We dwell on whether stress could lead to suicidal thoughts. We dwell on the big—on the—uhhhhhhh, excuse me I’ve gotta start that again. Let’s start the whole thing again.’

But the poet and his words, as seen above, have never been subtle. This is their power. Cooper Clarke handles everything with characteristic quick and crude comedy:

‘Let’s get this right. Christ, this is small font. I’m not used to this; I don’t read insurance policies…See, I’m new at these. I don’t even fucking know these poems, they’re that hot off the press.’

And just like that, he had the audience in his hands. Despite the stumbling, the poems read are evidently smart and sarcastic, sometimes silly, sometimes a little more profound. ‘Where the Worried Well Dwell’ takes on the guilt of the privileged; ‘Rolling News Blues’ targets the media cycles. In honour of Valentine’s Day, a re-reading of the famous anti-love poem ‘Are you the Business?’ was a welcome reminder of Cooper Clarke’s odd romantic streak, his way of telling someone that they are, in fact, the business:

‘Did Buddy Holly wear horn-rimmed specs?

Is Czechoslovakia full of Czechs?

Did Sigmund Freud consider sex?

Are you the business?’

After the reading, the Q&A commenced, and the chaos continued. Cooper Clarke’s circuitous way of answering questions makes him seem somewhat like your grandpa at a party…if your grandpa was also really quite cool. Digressions included a description of The Tardis, the legendary 90s club which ‘brought together artists and the crème de la crime,’ of the fan mail he would get from jails–‘You can’t buy that kind of exposure’– and of the poems about chlamydia and cadavers he had written for the NHS. At one point, he asked Murray to hand the mic to his friend and fellow poet Tim Wells, who ‘had a question for him.’ Wells did not wait for the microphone to land in his hand before shouting from the back of the hall, ‘I haven’t got a fucking question!’

Rather than promote his own collection, Cooper Clarke devoted a significant portion of the evening to encouraging young poets: ‘It’s an accessible mode. All you need is a pen and paper.’ He even cited the cathartic benefits— ‘Some people find poetry very helpful for their mental health and things like that.’ Though he added with a smile, ‘But you know…nothing wrong with me.’

Answering one of Murray’s questions on the voice of his poetry, Cooper Clarke was quick to insist his poems are dramatic positions, ‘performances instead of things I necessarily feel.’ Yet not two minutes later, he read ‘Get Out of Jail, Gaz,’ interrupting himself every three lines to provide auto-biographical detail on his relationship with Gaz and his sisters. ‘Yeah, there’s a lot of me in that one,’ he conceded.

If this article can communicate anything, it is that there’s a lot of John Cooper Clarke in every one of his poems. As Murray summarises, ‘You can’t read John’s work without reading it in his voice.’ The energy of the poet, of the evening at Conway Hall, leaps out of WHAT. The collection is a testimony to a long career of stubbornness and talent from a man for whom poetry was never a question:

‘I’ve always intended to be a professional poet because it was the only thing I was ever good at. I was advised against it in the strongest possible terminology, but I was quite pig-headed about it. I said, “If not that, what.”’

WHAT is the word.

Featured image courtesy of Gerard Jenkins.