AMELIA MCGARVEY revisits Robert Altman’s Images (1972).

What drives a woman to drive her husband off a cliff? is a question few have been bothered to answer since directorial giant Robert Altman posed it in his 1972 psycho-thriller Images. Is infidelity of the mind or the body? How much should a child know of their parents? The film, now over fifty years old, has been long forgotten by critics and audiences alike for reasons that have always baffled me. The bizarre, rural horror maps the story of children’s author Cathryn (Susanna York) and her jolly but unsympathetic photographer husband Hugh (René Auberjonois) in their retreat to the Irish countryside after a series of distressing phone calls which tumbles Cathryn into hysteria.

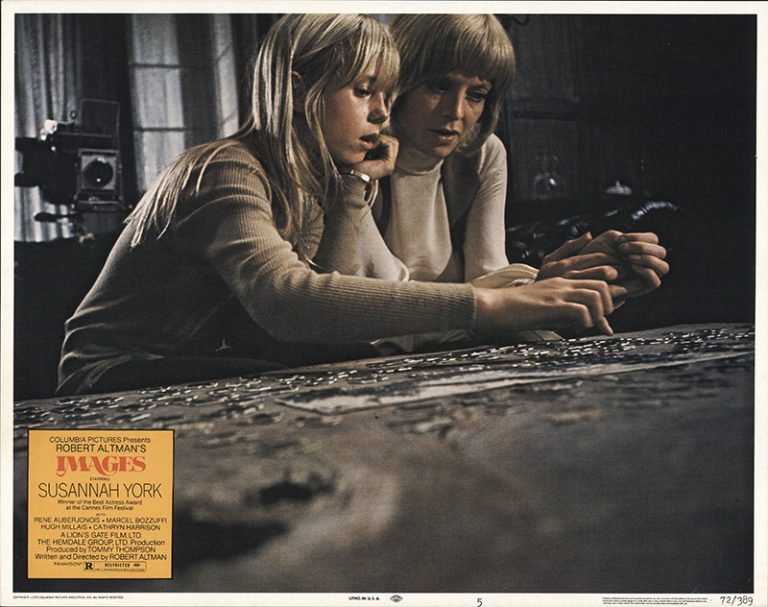

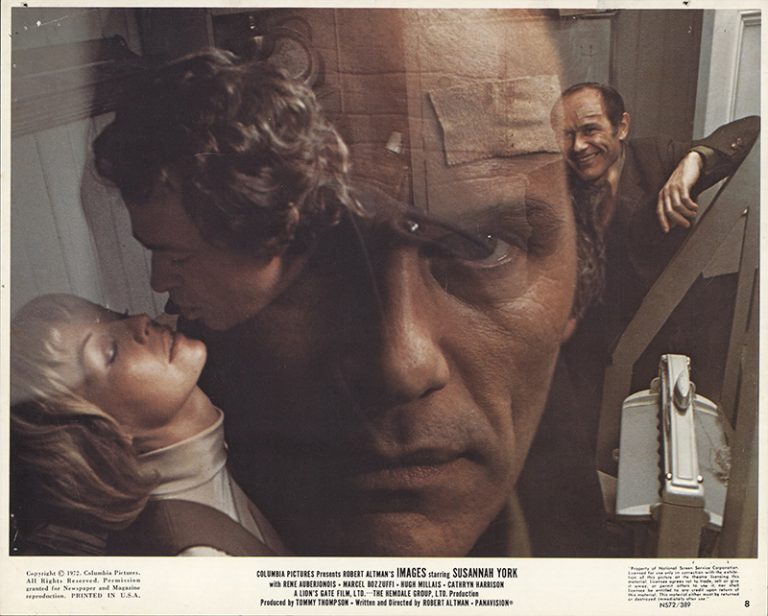

From here on out, slow zooms and open set design parallel the protagonist’s solipsistic regression into the imaginative mind, populated with schizophrenic visions of döpplegangers and ex-lovers alike. The fluency of the camera movements, at times lyrical and other times jarring, allows the characters to lapse into each other in moments of sexual ecstasy and blinding anger. Hugh disappears behind a wall and out emerges Cathryn’s dead French lover, René (Marcel Bozzufiand). In another scene, she hallucinates the murder of another former lover, her neighbour in the Irish countryside, Marcel (Hugh Millais), only to hear that he is alive and well from his daughter, Susanna (Cathryn Harrison). Note the fluidity of names between actors and characters. Susanna becomes, through the spatially transgressive use of mirrors and multi-angled shots, the younger twin of Cathryn, her confidante.

Contrary to Altman’s usual style, we get few examples of overlapping dialogue, if any, but a similar sense of claustrophobia and disorientation is nonetheless created through visual effects: most notably, how characters will be exchanged for one another mid-conversation or even mid-embrace, leaving Cathryn and the viewer alike conflated between the real and the imagined, always betraying our own senses. The choppy but witty dialogue recalls how Altman drafted and redrafted extensively his script throughout production, and the rapid shifts in tone give whiplash to an audience trying to decipher the events rolling out before them. Cathryn is a wholly unreliable protagonist, but we inevitably come to identify with her and experience her downfall simultaneously. Whilst we don’t want to hate the epicene, prep-schoolish Hugh or his childish jokes, we too learn to resent him for his inability to understand his wife’s schizophrenia. Critics have gone back and forth as to whether the film accurately portrays female anguish and sexual guilt, and I would agree that there is certainly something male-minded about a story which contextualises the female psyche exclusively in suggestive fantasies of sex and sexual violence. Yet by making the viewer explicitly privy to the hallucinations that Cathryn attempts to repress, Altman invites, or rather forces, into empathy.

Images marks an unexpected withdrawal from Altman’s otherwise sunny, Americana filmography of the 1970s in a way that critics have historically struggled with. When we compare it to sundried blockbusters such as The Long Goodbye (1973) or 3 Women (1977), Images is a strange and blustery puzzle of a film with its British humour and an indulgently haunting score by the legendary John WIlliams. Roger Ebert and Pauline Kael disapproved of its lack of emotional or psychological depth; others simply saw it as inferior to other zeitgeisty, folkish, and surrealistic tales of hallucination and artistic turmoil such as Polanski’s Repulsion (1965) or Bergman’s Hour of the Wolf (1968) and Persona (1966), not to mention the countless British-made films of the decade which explore the violence and strangeness of our native windswept rurality all by themselves — although, dare I say, I think Altman’s offering holds a merit of its own. The film is surprisingly British despite coming from one of the most all-American directors of all time, and I think it is this unexpectedness which has always confused audiences. If we shed our expectations of an Altman film and take Images for what it is — a chilling, seductive psychological thriller with a shocking ending just short of being cathartically just — we can learn to swallow it whole, and enjoy it.

There is so much to love about this film. Aesthetically, the cinematography, set design, and costuming are on point. Susannah York’s performance, replete with her moments of snark and despair, is sumptuous and captivating and we can’t help but be charmed by her recital of Cathryn’s fairytale at various parts in the film, which the actress herself wrote. When I compare it to my other favourite Altman film, The Long Goodbye, there are clear similarities in terms of clever dialogue and chic, modish art direction that mark the director’s usual style, but where Images delineates from its peers is in its core Britishness, its journey into the potential for fairytale horror inherent in the panoramic Celtic countryside. When Altman rehashed similar themes five years later in 3 Women, he did so with his usual Californian flair and created one of the most critically appreciated films of his career, but, I would be inclined to say, Images will always reign superior in my heart.

Featured image credit: fffmovieposters.com