After attending a talk with Slavoj Žižek at London’s Conway Hall, ESTER FREIDER reflects on the thinker’s peculiar presence, his appeal to Gen Z, and his new book launched at the event, Too Late to Awaken: What Lies Ahead When There is No Future?

In the 2011 documentary film Marx Reloaded, Slavoj Žižek describes the kind of communism he endorses as ‘a society where you, everyone would be allowed to dwell in his or her stupidity.’ I think this quotation sums up quite succinctly the kind of welcomingly cruddy atmosphere that he builds as a speaker: everyone’s a fucker, but what makes us fuck around the precise ways that we do?

Obviously, Žižek is a prolific philosopher, political theorist, and author of very serious books. But compared to the other contemporary theorists I follow (most of them women), I think of him more as that guy sitting at the back of the bus who’s high on shrooms with his buddy and won’t shut up about ‘human nature’. Most young people who have encountered his face online have become acquainted with him through a brief, snotty (I mean that literally rather than figuratively) video excerpt of a lecture where he provides commentary on a WW2 joke or maybe a TikTok impression of him by an assistant treasurer of some uni’s Socialist Society who’s brave enough to attempt a Slovenian accent. Those who are more interested might attempt a few rambling lectures or a book or two, but I think most of us think of him quite cartoonistically and materially, especially in regard to other thinkers today. Why so? And does the virality that springs from his strong oral presence actually translate to meaningful leadership as a thinker, or is it just rigorous rantwork?

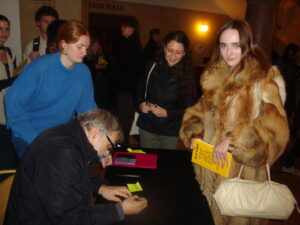

On my way to attend the interview and book signing for his upcoming book Too Late to Awaken: What Lies Ahead When There is No Future? I tried to keep such questions in mind. The event was held in the under-appreciated Conway Hall – I had attended events there before, but never in The Big Room. Complete with a three-sided balcony and a wall imprint over the stage that said ‘To Thine Own Self Be True’, I eagerly awaited the entrance of the beloved sweaty legend himself. I looked around to see many more young people than old, which surprised me, and also, a couple UCL tutors whom I recognised. The event was scarcely advertised – I had only found out about it through ERA – so I wondered where younger people had heard about it, or why they thought it was important to go. How many people were there just for the double-articulatory bit (‘I met the memey guy’ + ‘I’m intellectual enough to go to something like this’) and how many people really wanted to hear what the book was about? I imagine most, like myself, were a mix of the two.

We didn’t have to wait long. The interviewer introduced Slavoj with a funnily reflexive tone to his own use of the formality, and the world’s most controversial philosopher bumbled onto the stage, at once rambunctious and playful. After the first question was asked, the interviewer didn’t get another word in for at least 30 minutes. The question was indeed, for Žižek, only a single small traffic cone on a wide plain from which to run in every direction. He polemicised a sex scene from Oppenheimer, the list of people who dislike him including Noam Chomsky, how we fall in love, and of course, the Israel-Palestine conflict. It felt almost like rhetorical jazz – after a while, I just fell into a lull and was taking notes without knowing how he got from one place to the next. He spoke of so many incidents, and alternated between serious global crises and pop-cultural mishaps so erratically that you started to feel a bit flattened, yet attentive to each byte of information on its own. That’s most likely why he’s done so well – his loose speeches chime with the postmodern condition and, at times, narcotically overstimulating, the nature of interfaces that young people spend a large portion of their time on, such as Instagram, Tik Tok, and X (although maybe not for long on that last one).

But sprinkled through maybe-too-quick assertions on communism’s history, Eurocentrism, and Jordan Peterson’s sanity, are some really poignant and awakening claims on how to effectively communicate with and understand ‘people’ in the broader sense. One of my favourite things he said was ‘It is not enough to tell the truth. It has to be told in a way that mobilises.’ He made this statement in the context of climate change policy and the action that COP26 failed to produce. But it makes me suspect that his rhetorical jazz might have been, at some point, a conscious choice rather than his natural default: to develop a connection with young students and the media, to get young people to feel less intimidated by forums of (Marxist) political theory and contemporary philosophy.

After all, as ERA editor Olivia, who attended with me, asserted after the event: ‘What he says is actually quite simple and common sense, and many young people are thinking the same thing but maybe are a little scared to say it’. In a time of globalisation in which ‘identity politics’ (I use the term very shyly) is central to online political discourse and any form of objection to ‘self expression’ can stain you, it can be hard to openly be critical of the link between an extreme importance placed on identity and the neoliberal commodification, atomisation of communities, and estrangement from the Other (I also use this word shyly) that easily follows. Žižek does that – he does it like your intoxicated uncle when dessert and a third beer comes around at Thanksgiving dinner, but he does it. That’s not to say he should be absolved of his prejudices – he’s expressed several opinions strongly against trans-rights in a very recent article for Compact Magazine, apparently with little research on the positions he was arguing. That soberly reminded me that even a globally celebrated thinker who speaks 5 languages is not an expert on everything, nor should his thoughts be digested without a filter. But I’m not one to neutralize all of a thinker’s contributions because some of his thoughts are disconnected or under-informed (I think that’s bad identity politics, in which we assume something that someone has said allows us to dispose of them as a whole).

In terms of the publication itself, it leans on the more accessible side compared to some of his heavier theorisations on Lacan and Hegel, with friendly big font and almost two pages of the introduction using kopi luwak as a metaphor for the state of global politics today. It’s focused on the idea of the future being predetermined, and the past rather only forming retrospectively, when history appears to ‘become necessary’ for what’s happening in the present. As an example, Žižek brings up a supposed incident between Henry Kissinger and Zhou Enlai, the former Prime Minister of China, in 1972. Kissinger asked Zhou what he thought about the 1968 rebellion in France. Zhou replied: ‘It is too early to tell’. In the same spirit, I proclaim that Žižek’s presence has a level of ambiguity that makes his influence – the crowd he gathers and the crowd he appears to create – currently too pervasive to view with an assertive criticality. His morsels of affect are quite scrollable, piquant, and conversation-endless. But is he a model for how we, as young people, should theorise politics, and more so, human nature? I say: it is too early to tell.

Featured image: Slavoj Žižek in his flat in Slovenia, 2010. Source: The New York Review