NATALIA MOSQUERA reports on the post-Booker frenzy at Foyles Charing Cross, where this year’s just-announced winner, Paul Lynch, was joined by his predecessor, Shehan Karunatilaka, and presenter Anita Rani.

On a freezing Wednesday evening, the 6th floor of Foyles on Charing Cross Road is buzzing as the literary world’s big players (see Gaby Wood, director of the Booker Prize and Simon Trewin, agent of the moment) are chattering amongst themselves. “Congrats,” someone leans over, patting Trewin on the back. “Surprised?” he laughs.

Trewin’s client was not the clear favourite in the race to this year’s Man Booker Prize — not even the favourite among the three authors sharing his name — and yet as Paul Lynch walks onstage, the crowd claps with clear admiration. The writer of the now Booker prize-winning Prophet Song has been engulfed in a media frenzy since the announcement just 72 hours ago. RTE, CNN, BBC, The Financial Times, Channel Four News; type ‘Paul Lynch’ and find a flurry of recent results. ‘I just got off the phone with the New York Times,’ he exclaims, ‘It’s totally nuts!’.

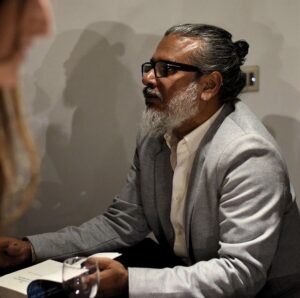

Tonight, Lynch is in good company, sharing the stage with last year’s winner, Shehan Karunatilaka. There is no one perhaps more able to relate: ‘Totally nuts’, he nods knowingly. The two authors are being interviewed by Anita Rani for what is Lynch’s first live audience since the win. He muses, ‘I used to wonder what it would take to get a live audience in London!’ Only a Booker, it seems.

In the first ten minutes, Lynch speaks almost exclusively in exclamation, his excitement apparent against the relaxed posture of Karunatilaka. Later, when answering questions dealing directly with the novel– queries surrounding genre, or the importance of ‘radical empathy’– we hear hints of the confident, assured voice found in Prophet Song. In these moments, it feels somewhat as though he is reading from a script. Trawling through his New York Times interview, I find the same response word-for-word to the question of the novel as political fiction:

‘A lot of political fiction begins with its own answer — it knows the problem and it knows the solution — and so therefore, it’s about grievance. And I think the work of serious fiction must instead be grief: grief for the things we cannot control, grief for what cannot be understood, grief for what lies beyond us.’

I recall this not to criticise Lynch — it is probably the fortieth time he has been asked this question, and it is certainly a good answer — but because it brings to mind the effect of all this media attention: the identity a writer is prompted to create, ‘the mask’ as Lynch puts it.

Karunatilaka speaks of the dissonance between the relatively unglamorous reality of being a writer —‘I sit in my room most days. If I’m in a good mood, I talk to my wife and kids. Other than that, it’s just talking to yourself’ — and the storm which is wrought by winning a prestigious prize: ‘Suddenly, everyone wants your opinion. Now my opinion on what’s happening in Sri Lanka, what’s happening with the cricket, is relevant.’ ‘My friend,’ he tells Lynch, ‘I really am relieved to hand it over.’

We often place pressure on our esteemed writers to present themselves in cohesion with their works, politically and otherwise. I think of Rooney as another Irish example, and the way Beautiful World, Where Are You deals with the notion of previous critical acclaim as an impediment to future writing. At the Booker ceremony Karunatilaka warned ‘you will not write another word for a year.’ Now Lynch expresses his anxieties around this:

‘The scary thing is that you do see writers who become the mask. They become the persona, and they forget actually who they are at the time…When you’re writing, you align with your deepest, most authentic self. And when you’re not writing, you’ve kind of lost that sort of place that you certainly belong to, you know? […] Your polarity changes when you’re outward facing. You can’t write. To write, you need to be inward-facing.’ Heads nod amongst the crowd, though he is quick to add, ‘But it is a privilege. I’m not — I’m not whining in the least.’ If Lynch does assume a ‘mask,’ it is pointedly a humble one in that regard.

After some back-and-forth bantering about the possibility of a Booker Band (both play guitar) and the revelation of what Lynch is spending his fifty grand prize money on (his mortgage, ‘it’s gone up 75%!’, in a very bleak reminder that even the glitziest event is not without the shadow of the cost-of-living crisis) — the conversation turns to the inspirations behind both Booker winners. Superficially, the texts are very different. Karunatilaka’s The Seven Moons of Maali Almeida is a second-person murder mystery, set amid the 1980s Sri Lankan civil war, in which the detective is the ghost of the eponymous deceased war photographer; Prophet Song is a bleak and claustrophobic portrait of a mother, Eilish, struggling during the collapse of democracy in a suggestion of Ireland. And yet, the evening illuminates a similar thread running through their respective motivations (future Booker hopefuls take notes).

Both speak of their desire to address collective amnesias: Karunatilaka, of the real casualties of the Sri Lankan Civil War — ‘Are people going to believe that these terrible things happened because they’re not being spoken about?’ — and Lynch, of what he describes as ‘the crossing of a line, which has recently happened and has not yet been articulated.’ (He read the line, ‘The next war is inevitable’ in Hesse’s Steppenwolf and thought ‘Here we are again!’) Both also recognise this inclination to amnesia, to disassociation, as a problem of overstimulation, and find an answer in attentiveness to the voices of individuals.

Karunatilaka: ‘Terrible things happen, and there’s investigations and then we put these things aside and move on to the next catastrophe. The ghost story is where these things are kept alive.’

Lynch: ‘Yeah. I think we’ve been bombarded by the spectacle for the last 30, 40, 50 years. I mean, we’re so bombarded that we eat our dinner while watching the news. And what is transmitted to us has no impact on us anymore. And it’s no surprise the self-defenses have to go up because if we truly, truly identified with what we saw, we wouldn’t be able to get out of bed… As I was writing the book, I found that the closer I could get to the moment, the closer I could get to the real, the more we inhabit the space where Eilish is, the more we are truly with her… The more the writing can push past and get around these defences and take us into literally into the heartbeat of the moment and get into that sort of hidden life, where there are the unrecorded acts that journalism cannot access, then empathy not sympathy becomes possible.’

As the writers deliver answer after answer, I find I cannot stop thinking about their earlier suggestion of fiction as compensating for a limitation of journalism. I am not alone in this. As questions open to the floor, a fellow audience member picks up that thread again and asks for elaboration. Lynch nods: ‘I look at work in journalism and I have enormous respect for journalism. Journalists are always trying to get behind the scenes, down to the ground, and they do it amazingly. But at the same time, they can’t capture that moment. They can’t capture, they can’t put you into the perspective, into the shoes, into the heartbeat, into the feelings, into the psyche of somebody who’s going through something, whatever it is…when we read, we are entering into the simulation. We’re entering into an extraordinary virtual reality device of some kind. It’s fiction! That’s what I’m talking about.’

Karunitalaka concurs, ‘These periods have been covered by journalists and historians, but they’re not still talked about because we have fresh catastrophes. And I think this is where the fiction writer can come in. You don’t need to have a message. You can present different narratives, divided opinions and start a conversation. I think fiction writers are pretty useless most of the time, but this is a service we can offer, and–’

Lynch interrupts, with a kind of fervour, ‘I completely agree! The present is interpreted by historians, by journalists. Fiction offers an opportunity to escape interpretation. To pose questions instead of framing answers…’

I am suddenly reminded of Lynch’s earlier comment about political works as vehicles providing answers — the recurrent phrasing, the suggestion of an overarching thesis — and I think once more about what Lynch’s ‘mask’ might be. There is a bleak cynicism to his worldview, blatant in Prophet Song, and a level of irony around the persona of ‘the writer’ in his stated self-consciousness of that posture. But it is clear on this stage, through the many phone interviews, in the countless written articles, that Lynch takes an unwavering stance on the moral significance of fiction. In a year where Arts Council England (ACE) cut £50 million from London-based arts organisations alone, justifications of the sustained, even heightened, importance of fiction are critical. So, as Rani wraps up and the writers walk over to the signing table, I think maybe it is no bad thing for Paul Lynch to have to be outward facing. Until next year’s Booker ceremony at least.

Featured image courtesy of The Booker Prize.