MARISA BECIROVIC tackles the age-old question of the origins of artistic genius, musing on whether it is the result of one’s environment or something more intangible.

The question of ‘the origin of the artist’ is one that shall simply never be answered (I’m afraid you’ve been misled by the title). I’m not going to weave back the threads of human history to pinpoint the exact moment when the conception of ‘the artist’ occurred, nor shall I speculate by whom or at what point it was decided necessary to class a subset of the population as gifted creators of beautifully inspired things. No, instead I contemplate the individual. I reflect on the personal origin and proliferation of ‘the artist’ and look no further than the end of my hand to discover where it all begins.

We are because others were before us – from origin to original

Just as the human race strives to reproduce in preservation of its genetic material, so do, it seems, artists. The young soak up what the masters present to them, preserving the transfer of knowledge and skill, while at the same time consistently reinventing the entire discipline of art, an absolute rejection of all it has stood for until this point. Realism is slashed by the Impressionists, the Expressionists challenged by bold Surrealists, so on and so forth.

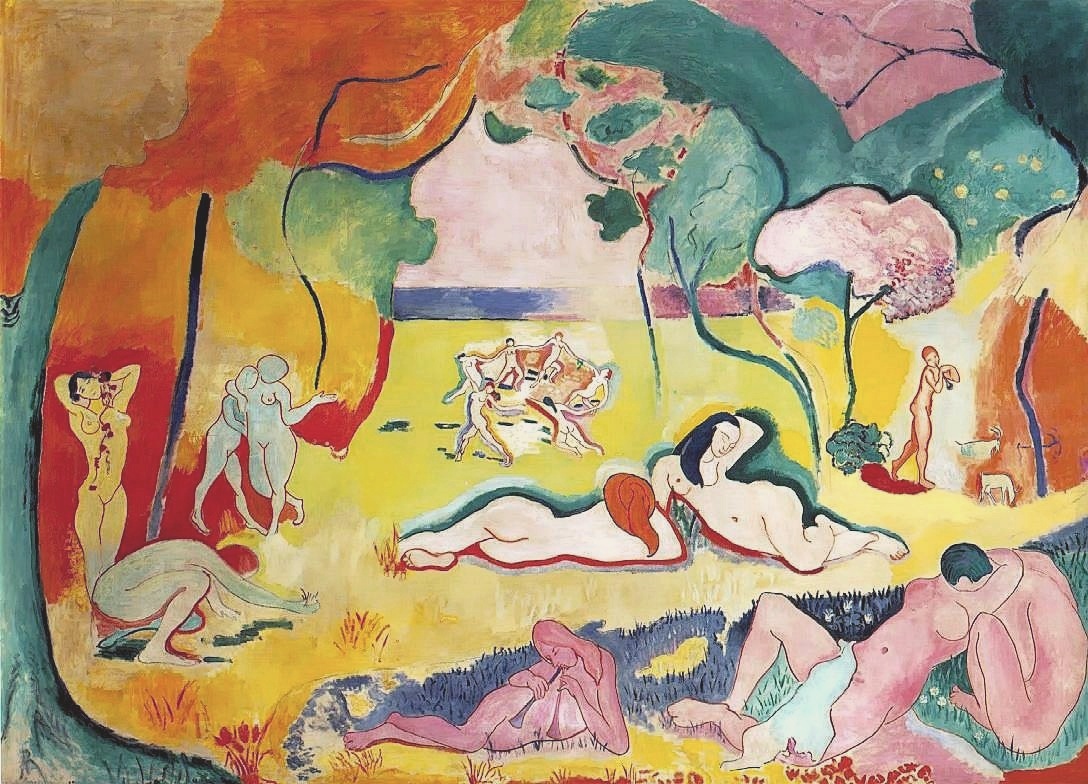

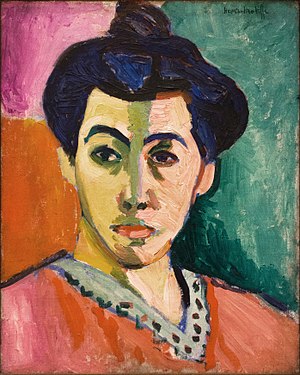

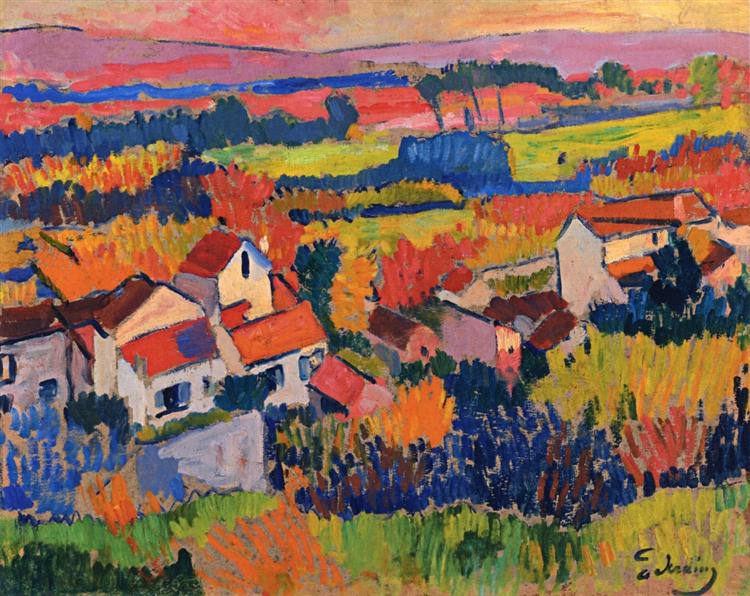

Pablo Picasso, a great pioneer of the artistic genre Cubism, is a striking example of the evolution and redefinition of what constitutes as ‘art’. Prior to the establishment of Cubism between 1907-14, Fauvism (from ‘fauve’ meaning ‘wild beast’) was the radical style of the times, founded by artists such as Matisse. It was a movement of bright colours and expressive, ‘wild’ brushwork, expanding the use of colour and painterly technique to bolder limits. Fauvists and Cubists were working alongside each other; however, the notes of Impressionism still linger within the Fauvist palette and technique. In contrast, Cubists adopted a new, angular yet muted perspective on the world, arguably a more dramatic evolution of artistry. Yet, it is not limited to the generational evolution we see in biology: the French painter Derain, for example, moved from the Fauvist style to Cubism in his own lifetime.

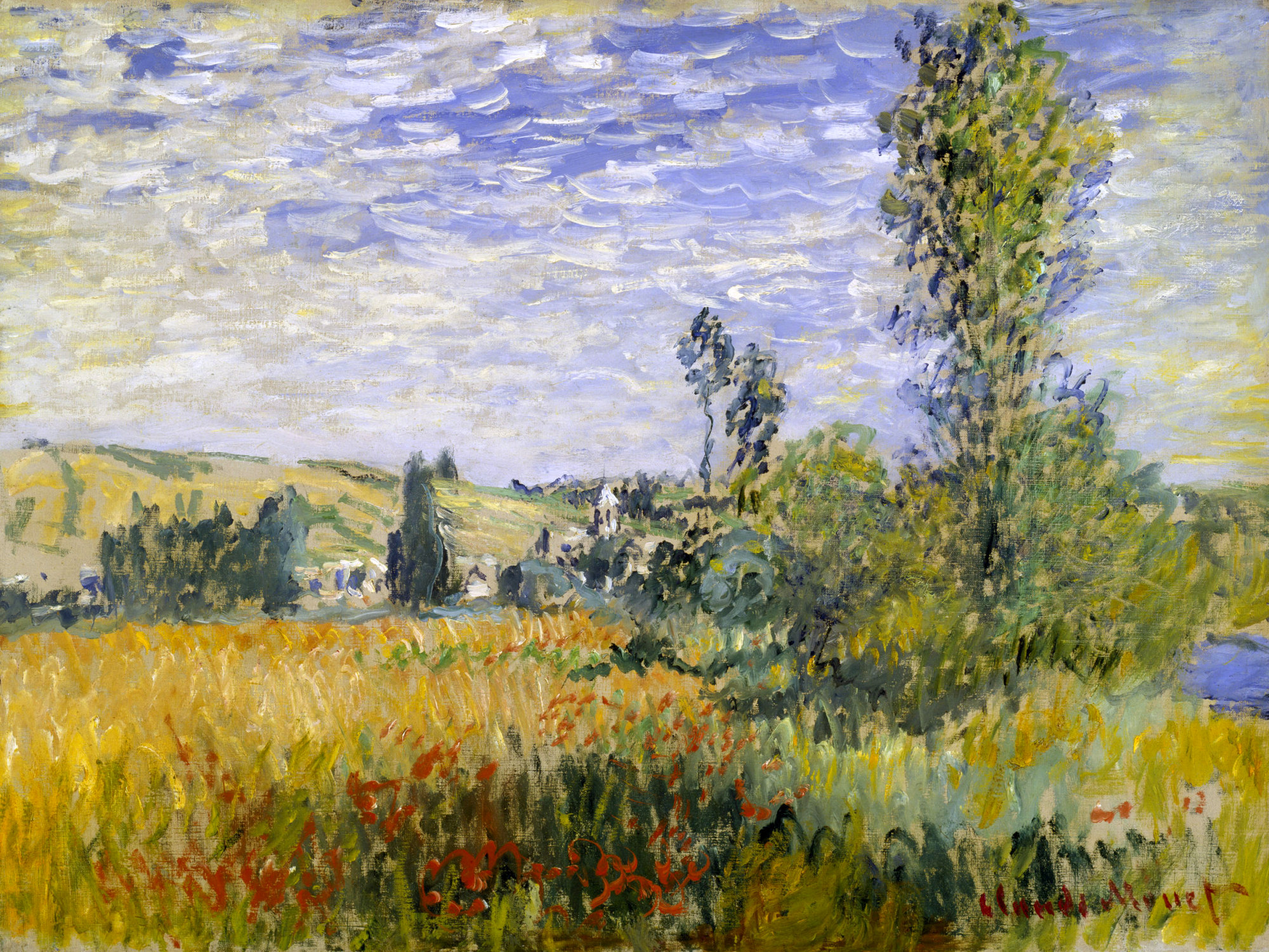

We find our origin and evolution in a constant battle between admiration, inspiration and absolute rejection of the old and ‘done before’. Just as parents are adored by their children who grow up to eventually challenge and break free, so too are artists in a cycle of childhood, of adolescence and finally, the object of the next generation’s rebellion as illustrated above. However, there is also a great sense of carrying forward the strides taken by previous artists. This web of inheritance means that the characteristics, skills and perspectives of one artist can be subtly seen in the work of another artist generations apart, similar in transference to that of biological inheritance. Much like I have my grandfather’s nose, Cezanne’s colour palette glimmers in the works of Matisse, and Van Gogh’s strokes wink with the thought of Monet. It is from these timelines of collective artistic experience that we create a pool of knowledge, and are pushed into advancement and originality.

The environment makes the artist

It can’t be denied that surroundings shape a person. Like a bacterial culture incubated at the right temperature, so too do the outputs of artists mature and grow in the warmth of varied social climates. I’m not comparing creative individuals to the stuff you kill with Dettol, more so the happy accident of penicillin. I believe the theory that our environmental origins have a large influence on the people we become has merit. This concept of ‘environment’ sheds light on the meaning of art and the purpose of artists. It has the function of creation, documentation, protest, exploration, all in the context of our surroundings.

It is our cultural origins and experiences that shape the way we see the world, how we interact with it, and how we choose to express our thoughts and ideas about it. Speculatively, Sorolla would not have painted the beaches of Valencia had he not resided there, nor would Picasso have created Guernica as a response to the Spanish civil war had it not been so close to home. Is it, then, that we play a random game of ‘right person, right place, right time’? Are the circumstances that talent finds itself in, indeed the critical factor? Perhaps, and thus we acknowledge the uniqueness of each individual, and recognise the essence of art and the origin of the artist: human experience.

I was born this way

Naturally, I shall now reject all of the above. It is too satisfying to not lose oneself in the age old question between nature and nurture. We apply it to the conception of all things human, and the origin of artists is no different. Louise Bourgeois succinctly states ‘artists are born not made’ and it is difficult not to agree to some extent: look at any child and you recognise the curiosity and creativity of an artist in them. Some might even go as far as to argue that it is in fact our oppressive surroundings that iron out the creative streaks we are born with, and that we must ‘re-learn’ the artistic inspiration we inherently possess from birth. We might as well not distinguish between ‘artists’ and ‘people’, as art is something so intrinsic to our nature. The creatives among us, observers, painters, musicians or dancers, need look no further than the plethora of work before them, the collage of individual and collective wisdom, to decode the origins of the artist.

Featured image: Henri Matisse, Le Bonheur de Vivre, 1905-1906. Oil on canvas. 176.5 cm x 240.7 cm. Barnes Foundation, Philadephia, Pennsylvania. Image courtesy of Wikipedia.