ZSÓFIA PAULIKOVICS explores the relationship between music, women and automobiles.

In 1991, Ridley Scott’s iconic road movie Thelma and Louise premiered to critical acclaim, catapulting its stars, Geena Davis, Susan Sarandon, Brad Pitt (and a 1966 Ford Thunderbird) to an almost immediate cult status. According to one Telegraph feature, ‘Star Cars – Where are they now?’, five different ‘T-birds’ were used for filming, one of which sold for $65,000 at an auction in 2008. Thelma and Louise follows two friends, Thelma Dickinson and Louise Sawyer, as they set out on a two-day vacation from their home in Arkansas. Thelma has secretly left and run away from her husband, a controlling and manipulative man. When they stop at a diner, Thelma is assaulted and nearly raped and Louise shoots the assailant. The two women take to the road, picking up a hitchhiker, who later steals Louise’s life savings. They keep driving as their circumstances become increasingly impossible, until eventually they are cornered by the police on the edge of Grand Canyon. The film was lauded as a feminist trailblazer and received six Academy Award nominations, among them Best Actress nominations for both Davis and Sarandon. But regardless of its success, rather than creating a precedent for other female actors to follow in their shoes, Thelma and Louise stands alone as a female-led road movie. In fact, the only other film with a female lead that appears in the aforementioned Telegraph article is Herbie: Fully Loaded (2005) starring Lindsay Lohan.

26 years after Thelma and Louise, Susan Sarandon plays a mechanic in the music video for Justice’s latest single ‘Fire’, taking Gaspard Augé and Xavier de Rosnay for a spin in the desert on a mirror-polished convertible. ‘Fire’ is featured on Woman, the electronic duo’s first album since 2011’s Audio, Video, Disco. With its 80s electro-funk synths, the song possesses Justice’s signature blend of futurism and nostalgia. Sarandon is shown dancing in slow motion, wearing faded blue Levi’s and a white t-shirt. Whilst the video is a clear homage to Thelma and Louise, choosing Sarandon feels in no way sentimental: the lyrics ‘Lovers need no reason / Lovers need no season / It’s a game of give and nothing more / Lovers need no reason /Lovers need no season / The golden key that opens any door’ are repeated throughout the song and the beat has no real climax – without the video the song would sound repetitive, even a little flat. In an interview in Rolling Stone, de Rosnay spoke of the difficulty of keeping up with EDM’s rapid pace: ‘To be relevant in the [club] scene, you have to be young and […] embrace that. Every year there are new people […] who make this amazing music because it has their energy and sounds like nothing else that has been made before.’ ‘Fire’ is like a blissful limbo, a moment of suspended escapism. At one point, although they are driving towards it, the horizon seems to jump gradually further and further away. Lined with windmills like a mechanical forest, the scene is like a trompe-l’oeil desert mirage.

In the newly released Rolling Stones cover of Eddie Taylor’s ‘Ride ‘Em On Down’, Kristen Stewart, similarly clad in vintage Levi’s and a ripped white t-shirt, drives around a post-apocalyptic LA in a metallic blue Ford Mustang. The roads are deserted. The only other person alive seems to be a policeman, who only pulls Stewart over to ask where she filled up her tank. Drifting around in a dried up riverbank, she only slows down when a zebra cuts in front of her path. The empty boulevards juxtaposed with the familiar urban setting create an otherworldly feeling. Ultimately, Stewart’s driving seems to be completely lacking in purpose – other than blasting music, dancing barefoot at an abandoned petrol station and having a damn good time. In perhaps the most famous 20th century work of the road trip genre, Jack Kerouac’s On the Road (the 2012 movie rendition of which Stewart appears in as Marylou), driving is ground zero. Protagonists Sal Paradise and Dean Moriarty aren’t running from anything but rather running to something: a destination, a partner, a dream. When you have somewhere to go, you are never without purpose. Being on the road is Sal and Dean’s raison d’etre and with them the novel’s. When women drive though, as in Thelma and Louise, it is to get away from something – a man, a crime, or a life so monotone it seems to stand still.

Rihanna’s video for the 2016 instant classic ‘Bitch Better Have My Money’, sees her kidnapping and holding hostage the wife of her accountant who has embezzled her money. She drives across the country from motel to motel alongside her two henchwomen. The video packs in an impressive number of film references, among them the infamous 1965 Faster Pussycat! Kill! Kill! in which three go-go dancers kidnap a young girl and haul her across the desert. Like its ’60s predecessor, it was vilified for aimless violence; but dismissing it as merely outrageous sensationalism is reductive at best. ‘Kamikaze if you think that you gon’ knock me off the top/ Shit, your wife in the backseat of my brand new foreign car’, she sings. Here, the car is a display of wealth and power – a symbol of the upper hand that she had been robbed of. Admittedly, the kidnapped wife here is as much an object as the car itself – not quite following in the footsteps of Thelma and Louise.

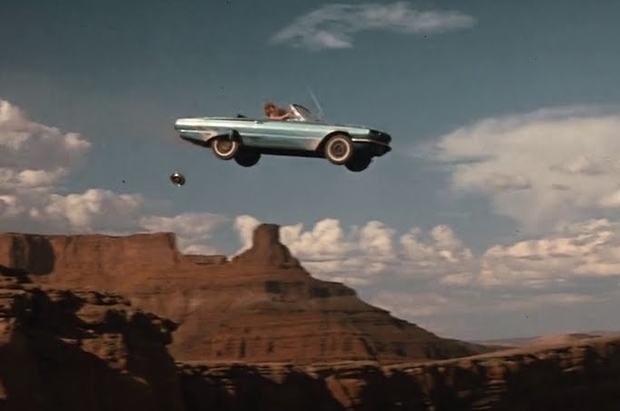

At the heart of the road trip fantasy lies the idea of its endlessness, its suspension in time. Neither here nor there, a kind of travelling purgatory, a road trip is a world in and of itself, a microcosm made up of the car and the road. The destination is unimportant, insignificant even, so long as you keep going. In the iconic finale of Thelma and Louise, the two women are seen surrounded by police, a hundred yards away from the edge of the Grand Canyon. ‘What if we just kept going?’ asks Thelma. And so they do, holding hands as Louise drives over the cliff. The last shot shows the T-bird suspended in mid-air, as the picture slowly fades – first the Canyon then the car, as though we’re watching a polaroid form in reverse. To all intents and purposes, they didn’t get caught, they just kept going.