ANNIKA THORBORG reviews Milk Teeth, a newly translated novel by German author Helene Bukowski.

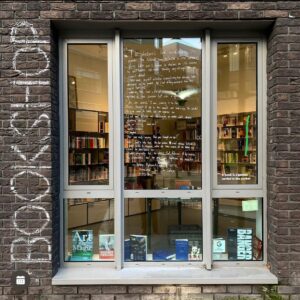

Hidden in a tucked away corner bordering North and East London, the

bright lights beneath a brutalist building guided me towards Hoxton Books, a quaint bookshop where warmth, shelter, and an exciting book launch awaited me. I didn’t know much about Helene Bukowski’s Milk Teeth, only that it had recently been translated from German to English by the talented Jennifer Calleja, and that the phrase of the day seemed to be `eerie climate fiction´. What I did know, however, was that if the novel was even remotely similar to any of the unsettling German Netflix series that I have watched (my favourite being Dark and Dear Child), then I would be sure to love it – in fact, Bukowski teased us by hinting at a future show adaptation of Milk Teeth.

The reader is pulled into the book through the eerie tone of the opening lines:

‘The fog has swallowed up the sea. It stands like a wall, there, where the beach begins. I can’t get used to the sight of the water. I’m always looking for a bank on the opposite side that could reassure me, but there’s nothing but sea and sky. These days, even this line is blurred.’

The conditions of the world that the main character, Skalde, occupies are hazy: we learn that she lives with her dying mother in a stagnant, slowly deteriorating, environment. Suddenly, she finds a lone child in the woods, a young girl by the name of Meisis, who is seeking refuge from her own world. The protagonist is hesitant to take Meisis in as her home is riddled with secrets not meant to be unravelled. Beautifully written in spare prose and clutters of poetry, the novel follows Skalde overcoming her hesitation and taking on the role of Meisis’s mother.

Milk Teeth is a captivating tale exploring the themes of boundaries, motherhood, and immigration in a world unnervingly similar to our own. Its sharp, short sentences and quick pace make it an easy read — after the event I practically swallowed the entire book on the tube home — and despite the profoundness of the topics discussed, Bukowski has structured the story in a way that doesn’t make you feel overwhelmed. She does so through short chapters, which could be read as stand-alone short stories, as she explained at the launch. She further noted that such structure stems from her initial preoccupation with short stories and a disinterest in a longer literary form — but once the characters of Milk Teeth had taken hold of her, she felt they had to be described in a novel.

The author then went on to emphasise what her goal with the book had been all along: she wanted to create a playful and reflective space between the reader and the world of Milk Teeth, where the reader isn’t given all the answers, but, instead, is left on the edge trying to fill in the blanks. Such a dynamic is achieved through the absence of dialogue: with few voices to interact with, we are left revelling in silence. Instead, the novel showcases what can be described as a kaleidoscope of alternative communication modes, such as an added focus on body language or the recurring motif of drawings, which leaves us with implicit reports and a craving to piece them together into something resembling the truth, a complete image. The poems closing the chapters, such as, ‘I SAW THE BLUE OF THE SKY, IT LOOKED AS IF IT HAD BEEN HOLLOWED OUT, AND I THINK THAT EVENTUALLY THE HOUSES WILL ALSO STAND LIKE SKELETONS’, work to move the reader closer to the full picture of Skalde’s world. Others, particularly the final one, forces us to reflect on our own existence and place in the world: ‘TO LEAVE A FAMILIAR TERRITORY I COULD NAVIGATE BLIND. WHAT LASTS, AND WHAT REMAINS, IF I GO? WHO WILL REMEMBER THE PATH I LEAVE BEHIND?’ This subtle game of detective that we are goaded into creates an interesting bond between the reader and the dying world. In this, we take on the role of an insider protecting their territory, and simultaneously become a rejected outsider looking for sympathy. It is precisely in this double identity that Bukowski so brilliantly interrogates what it means to belong in an environment heavy with rejection and resistance.

The novel’s preoccupation with social tensions and a brutal environment — a direct result of climate change, where the birds are ‘scorched’ and the plants are ‘bleached by the sun’ — comes together to create what Bukowski describes as ‘a modern-day fairy tale’, which only unfolds as such thanks to the pockets of care and sentiment scattered throughout the story. Instead of dwelling on ‘the dryness of the forests’, or on how ‘bit by bit, everything crumpled to dust’, Skalde appreciates waking up ‘next to the child and hold her hand, as if I had never done anything else’. It was through these soft and vulnerable moments that I fell in love with Bukowski’s characters. I probably shouldn’t have been reading it on the tube, because it left me in such a daze that I almost missed my stop. When I finally departed from Bukowski’s world, I was left with an entirely new view on the physical and metaphysical borders that occupy our own world, and a deep book-hangover.

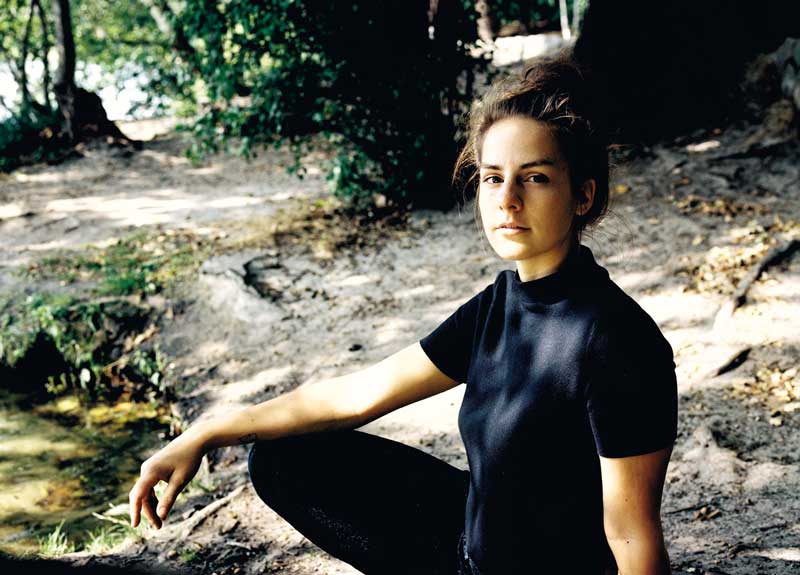

Featured Image courtesy of Rabea Edler.