MOZA ALMAZROUEI is in her third year at the Slade. She is currently studying remotely from Dubai. Her interdisciplinary practice is occupied with ideas of fiction, history and agency, which are explored through the concepts of archaeology and archive. JEAN WATT spoke to her about her work.

How have you found making work at the moment, now that you’re not physically at the Slade?

My work sits in a different physical environment at the moment [but] there is equal opportunity to being in the studio at Slade. Up until now I was mostly making sculpture in the studio and showing it in my seminars, so I never really left the parameters of Slade. But now, with these topics that I’m interested in – whether its archaeology or archive – it’s so different to visit the space itself and think how I can put my sculptures within that space. So it creates a different dialogue and is more multi-directional.

I found your artist statement really interesting; you said that you have these two strands to your practice, the archaeological and the archival, and I wonder if you could talk a bit about how these two aspects interact and how they’re different?

I mean they’re similar in a way, in that they both create exclusionary modes of knowledge or even existence. In terms of archaeology and institution, the myth that coincides with these sites or the people that inhabited these spaces is suppressed. I think that’s applicable to an archive as well. There’s a difference between reclaiming and having ownership of such colonial documents. So, naturally, these forms of knowledge production leave things off the margins, and that’s what I’m interested in and that’s what a lot of artists are interested in; the gaps of knowledge that are created within both of these subjects.

It feels ongoing, an excavation and also a manifesto. It seems the archaeological side of your practice is more sculptural whilst the archive is a collection of mixed media, could you talk more about the mediums of the two?

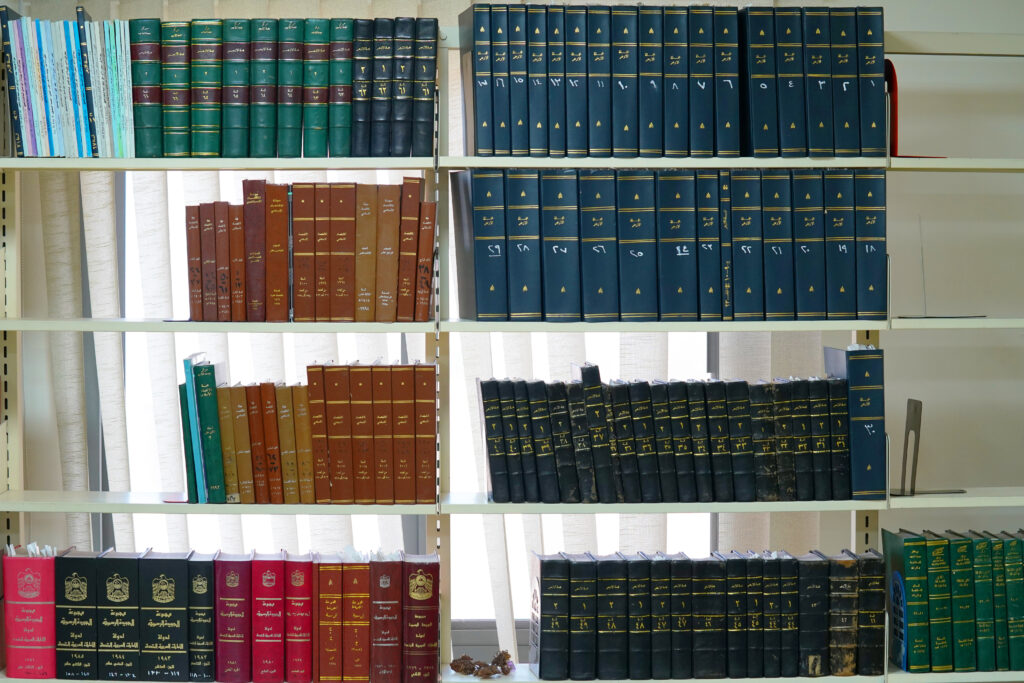

For me, how I first approached the archive is so different to how I approached the archaeological side. I stumbled across this book called Neglected Arabia about these British missionaries that were sent to the [Persian] Gulf, and there were these hymns that coincided with it. So my first idea was to think about how that hymn would sound. When performed, it becomes a form of transformative recognition, where it’s no longer a violent text that sits in a book amongst other books. I also made an object at the start of the archive and then placed a remnant of it within the photograph of the bookshelf. I wanted to consider what processes that object would have undergone to be placed within that space. But I guess that’s where the two aspects of my practice link: with the archive, or some form of document, I like to think it has some sort of contingency to the present and the future. [And then,] looking at an archaeological site, they are more than just historical probabilities.

Yeah, it seems like you’re working across a past, present and future that is really fluidly re-articulating narratives. How influenced are you by writing?

I would say, Octavia Butler’s Bloodchild, really struck me as a child. In the foreword, she says the story isn’t really about slavery [despite how it is commonly interpreted] … This openness to other possibilities is what struck me. In terms of the archival work, I think I was interested in understanding what language is, in order to look into archives. I was looking at Ghostly Matters by Avery Gordon; she sort of creates her own language to describe these margins. She talks about the ghostly aspect of these archives and says that these bodies exist within the peripheries and haunt us and she compels us to look into the invisible [aspects] of what is in an archive. In creating this language, it feels much more personal.

Do you find that your work feels like a personal archive?

I think for the longest time I tried to separate it. In terms of, ‘this is me as a person and what I make is separate’. But I sort of came to terms with the fact that I am a mediator and whether it’s an archival document which struck me, [or something else,] there’s a reason why it initially sparked my interest and I do make these objects; so I have a reference point and I try to respond to that through me or my object-making.

How do you find showing your work? Do you feel pressure to physicalise something, or is it more discursive? In your interim show, it was more of an installation, I wonder how you want your work to be realised…

I guess the issue that I’ve always had is that I start off with a reference point, but then when I make the objects and describe the context in which I made them, [viewers] don’t necessarily see the connection between what I’m saying and making. But I think for me, if it just gives an insight, like in my interim show, if it just insinuates that it’s on the verge of being pseudo-archaeology, then I’m happy with that. What I made for that show was collected stone and soap sculptures, and making soap sculptures had its own limits. It sort of embodied its own materiality, so how much can I shift that to fit into the context of what I want it to be? It was just fun to play around with that. There isn’t one direction of how I want my work to be taken. I always thought I just made sculptures, for like the first two years, and then I realised that if I create these boundaries that I’m ‘just making sculptures’, then I’m limiting myself.

You spoke a bit about writers who inspire you, I wonder if there are any artists or other sources of influence for you?

I think for the most part its been Walid Raad; he created this group called the Atlas Group which thought about how to play with this idea of para-fiction when you’re describing an actual historical event. I think that all the characters that he’s made up are so interesting, whether they’re archivists or philanthropists. There’s a plausibility that he plays with, which I’m interested in. And the fact that it’s all generated through him. There is something personal but you just don’t see it, there’s a truth somewhere.

That links to your description of yourself as a mediator, which is such an interesting way of understanding how you can position yourself in terms of what you’re making…

Especially when I’m looking at whether its a document or an archaeological site – if I do position myself at the forefront, then the questions of fetishising these documents or sites, do they still play on? Because I have some sort of authority over these objects that I make. Does that make me narcissistic or romantic? For me, [my thought at] the first instant was, ‘how do I separate myself from the objects that I make?’, but then I realised [maybe] that’s impossible because I’m the one who’s making the sculptures in the first place. That’s still in question, what’s the possibility of removing yourself?

You can find Moza on Instagram @moza.sfm and listen to ‘The Arabian Mission Hymn’ below