PAUL REDGRAVE explores the array of strategies needed to deal with multifaceted ISIS.

How does one define ISIS? According to the political scientist Joseph Nye, ‘the Islamic State is three things: a transnational terrorist group, a proto-state and a political ideology with religious roots.’ Yet, Western politicians act as if military intervention is the panacea for all jihadist threats. This is not the way foreign policy should be conducted.

We need to recognise that ISIS is a composite working on multiple levels. It is not just a proto-state with a conventional army, but also an ideology – and ideologies cannot be destroyed by bombs.

First, some basic information: ISIS-held territories in Iraq and Syria currently cover a swathe of land larger than the United Kingdom, although most of this is a barren desert. Mosul in Iraq and Raqqa in Syria are its most significant strongholds, acting as symbols of a homeland for fundamentalist Salafists around the globe. ISIS controls a population of eight million people, including 30,000 fighters. It funds itself, making between one and two million US dollars a day from taxing its population, oil exports, smuggling antiques, and the extortion of money.

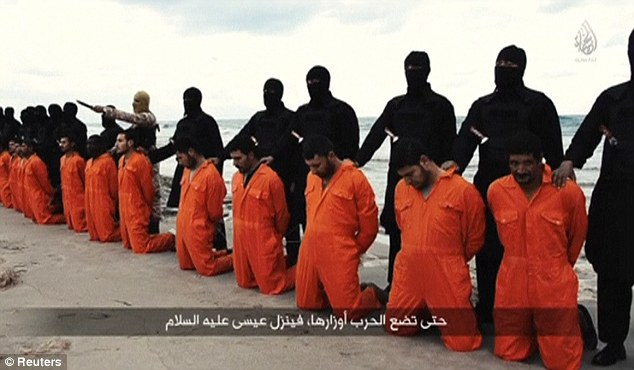

Nye is correct to use the label ‘transnational terrorist group’: ISIS bolsters its appeal worldwide by using the Internet to wage digital warfare. In late 2014, 46,000 Twitter accounts openly supported the group, and it recruits followers through private chat rooms and messaging systems like Whatsapp. Whereas Afghanistan witnessed an ‘execution’ of computers under the Taliban, ISIS has embraced mass media to disseminate its ideology. To fight ISIS, we first need to ‘neuter’ their online presence by suspending all UK accounts associated with their digital high command.

The spread of ISIS is rooted in systemic failures within the Arab region – which cannot be remedied by the Western war machine alone. Militarism only aggravates these problems. A more thorough discourse on diplomacy is needed, not just among policy analysts but also politicians themselves, who seem content to proclaim that bombs and soldiers are the only solution. Political analyst Phyllis Bennis elucidates that ISIS has ‘support on the ground, particularly from Iraqi Sunnis, particularly Sunni tribal leaders and their militias’. Why do Iraqi Sunnis turn to ISIS? Because of sectarian tensions exacerbated by the Shia government’s persecution of the Sunni majority; mass arrests, torture and extra-judicial killings all push Sunnis towards ISIS. Bennis calls for negotiations with the Iraqi government to curb this tyranny and diminish this ready-made support network for ISIS.

Diplomatic negotiations could effectively introduce an arms embargo, stemming the flow of weaponry into ISIS territory. Pressures needs to be exerted on Turkey, Qatar, and Saudi Arabia, who, by sending weapons to the Syrian opposition, are arming ISIS too – and risk assessments placed on arms exports to Iraq. States need to ratify the global Arms Trade Treaty, whose objective is ‘to prevent and eradicate the illicit trade in conventional arms and prevent their diversion.’

Nonetheless, dismantling ISIS through diplomacy is a long-term goal. Military action must play a role for now – to prevent further territorial gains and to protect persecuted groups such as the Kurds and the Yazidis in northern Iraq. Clearly, however, the current military policies employed by Western powers are not working. The US-led campaign since September 2014 has carried out approximately 3,000 airstrikes in Syria against purported ISIS targets, yet there have only been limited gains. The terrorists are able to adapt and move, making it increasingly difficult to identify targets. A spokesperson for the Kurds stated ‘each time a jet approaches, they leave their open positions, they scatter and hide.’ Intensifying the bombing campaign will only increase civilian casualties in Iraq and Syria, and further antagonise disaffected Sunni youth by presenting Westerners as meddlers.

Military policy needs to be effective – to mediate the fine line between avoiding the fomentation of sectarian conflicts whilst containing ISIS. Supporting the PKK, who protecting the Yazidi minority in northern Iraq, would achieve this. Instead, the US defends Turkey, who has conducted air strikes against the PKK they conflict with Turkish interests. As Noam Chomsky suggests, ‘the best outcome would be if ISIS were destroyed by local forces, which could happen, but it would require that Turkey agree.’ Once again, the importance of diplomacy is emphasised.

Defeating ISIS requires a plethora of strategies that can deal with a terrorist organisation which functions on multiple levels – with its recently acquired statehood, its digital presence, and its conventional army. We need to recognise the complexities involved in shaping foreign policy in the Arab region. Instead of flirting with extremes (militarism v. pacifism), we should be open to a more thorough discourse, divorced from our left or right wing biases. The truth is, threats like ISIS transcend these ideological paradigms. They require, more than anything, a willingness to seek out new solutions, rather than presenting pre-packaged solutions that just don’t work.