MAYA BOWLES explores the phenomenon of coronavirus conspiracies.

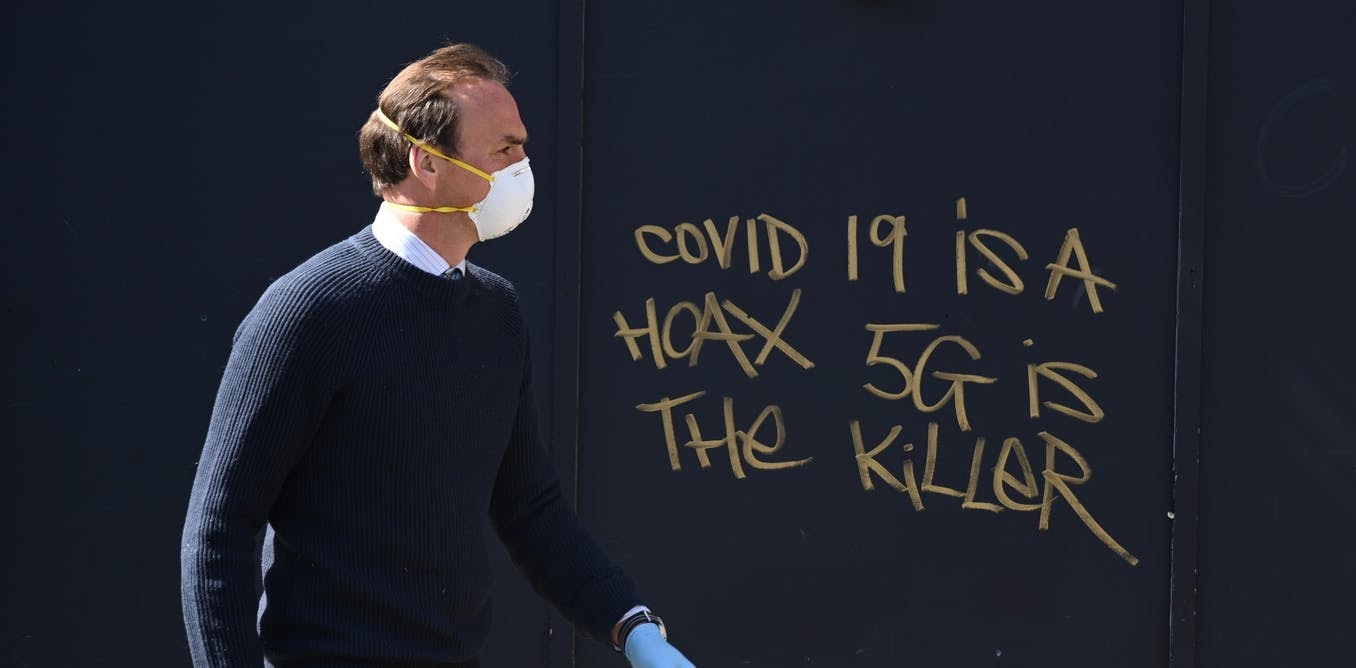

Conspiracy theories have always resided on the fringes of society and the deepest, darkest corners of the internet. Now, during the coronavirus pandemic, they have spread like a virus of their own. After discovering that a close friend of mine was sharing Covid-19 conspiracy theories on social media, I realised the extent of their infection. I also realised that I could no longer dismiss conspiracy theorists as utterly bonkers, and that I needed to try to understand why people believe these seemingly wacky theories.

While believing that the earth is flat or that the moon landing was a hoax is relatively harmless, Covid-19 conspiracy theories are far more dangerous. Research suggests that there is a correlation between believing such theories about the virus and flouting social distancing rules, demonstrating that the spread of these theories contributes to the spread of the virus, and ultimately the loss of life.

Coronavirus-related conspiracy theories are abundant yet nebulous. They are often inextricably connected and indistinct, existing in a kind of ‘rabbit hole’ – once you believe one, you start to believe them all. They range from the belief that the virus doesn’t exist, and is fabricated by the government to control us, to the belief that 5G masts are causing the virus. Many theorists believe that Bill Gates created the virus in order to enforce mass vaccinations, through which he could insert tracking microchips into the population. The people who believe these theories are often anti-masks, anti-vaccines, and anti-social distancing, resisting the public safety measures that they believe are part of an authoritarian effort to forcefully control the population.

I didn’t have to do much research to discover that many of these theories are deeply anti-Semitic. The Jewish billionaire investor and philanthropist George Soros has long been the target of conspiracy theories; it is unsurprising that he has become embroiled in the web of theories that spring from the current climate. These include beliefs that he (along with other high profile businessmen) is somehow behind the coronavirus, and that he ‘owns’ Black Lives Matter and Antifa, paying protestors to create civil unrest and radicalise African Americans in order to undermine American society and promote the ideology of the ‘radical left’. Soros has donated huge amounts of money to racial justice initiatives, but these theories are entirely unfounded and have been disproved.

Such theories about Soros form part of a network of anti-Semitic conspiracy theories that have been perpetually rife throughout history, all hinging on the belief that Jewish people secretly run the world. During the Black Death of the fourteenth century, mass persecutions of Jewish people occurred throughout Europe, as theories circulated that blamed Jewish communities for creating and spreading the plague by deliberately poisoning wells. This stuff is far from new; it is rooted in age-old prejudice.

So why do people believe in conspiracy theories? I was baffled that my close friend seemed to be falling down the rabbit hole, and I wanted to know if there was anything I could do to bring her out of it. My initial response – bombarding my friend with facts and articles in an admittedly patronising way – didn’t seem to work. To really engage in discussion with her, I needed to understand more about why she was thinking in this way.

CrowdScience on the BBC World Service recently aired a brilliant episode titled ‘Why Do Conspiracy Theories Exist?’. The episode follows a situation like my own, as a listener contacts the programme asking how she can deal with a friend who is sharing conspiracy theories online. One of the academics who speak on the programme is Karen Douglas, Professor of Social Psychology at the University of Kent. Douglas suggests that conspiracy theories are attractive because they give people a feeling of superiority and uniqueness, a sense that they have information that others don’t. It started to make sense that my friend had repeatedly dubbed me a ‘sheep’ – her beliefs made her feel special, different from the flock.

The CrowdScience episode also details the research of Jan-Willem van Prooijen, Associate Professor at VU Amsterdam. He explains that our brains seek patterns between stimuli, and when we feel scared, we often see patterns that aren’t actually there, a process he calls ‘illusory pattern perception’. It is no surprise, therefore, that conspiracy theories have exploded in popularity during the pandemic. Throughout history, there appears to be a clear correlation between conspiracy theories and global tragedy. In times of crisis, people seek clear explanations for events that are difficult to comprehend. Conspiracy theorists find it easier to believe that there is a ring of powerful people behind tragic events, rather than accepting that their causes are often far more nuanced and complex.

During the pandemic, we have all had to sacrifice some personal freedom in order to save lives. This loss of control has created ripe ground for the growth of conspiracy theories: the groups and pages on social media that promote conspiracy theories provide the feelings of community, belonging, and agency that so many people are missing right now.

While many of us may feel angry at the recklessness of these beliefs, anger and ridicule are not necessarily the best solution. Though Tova O’Brien’s scathing attack on conspiracy-theory-peddling New Zealand politician Jami Lee-Ross in an interview last week was praised by those who felt that his theories were ‘rubbish’, it will undoubtedly have stoked the fire among communities of conspiracy theorists, alienating them further.

If we approach conspiracy theorists with greater empathy, perhaps we will be more likely to get through to them. It was clear from my conversations with my friend that angrily bombarding her with facts, statistics and articles didn’t do the trick. Engaging with someone who is so far gone down the ‘rabbit hole’ clearly requires a more sensitive approach; it’s certainly not something that happens overnight. At such a testing time, with the mental health of so many at stake, human connection and empathy feel more important than ever.

Below is a list of fact-checking articles on the theories discussed in this article:

https://www.adl.org/blog/coronavirus-crisis-elevates-antisemitic-racist-tropes

https://fullfact.org/online/5g-and-coronavirus-conspiracy-theories-came/

https://fullfact.org/online/gates-patent-vaccine-wuhan-lab/

https://www.adl.org/disinformation-conspiracies-connecting-george-soros-to-protests-and-antifa

Featured image source: The Conversation