JOSH LEE explores our attitude towards the mental health of London’s students.

According to an NUS survey from 2013, one in five students feel that they have mental health issues, or have been diagnosed with a mental health problem. In light of this, the reader of this article is statistically likely to be friends with at least one person who suffers from some form of mental health problem, or suffers from one themselves. It’s a reality that is often trivialised by the larger part of society, or not even considered at all.

Relocating and setting up a new life is always an intimidating prospect, and depression, anxiety and paranoia are just a few of the potential mental obstacles facing university students the world over. But for students in our capital, these obstacles are perhaps more prevalent. On top of the £9,000 a year tuition fees, London’s rent prices are shamefully high. Add that to the overall cost of living in the city, and the brooding mountain of debt that befalls all students is certainly higher for those in London. What’s more, although the city is considered to be a concentrated, cosmopolitan centre, where rubbing shoulders with someone is a daily occurrence, London can indeed be an intimidating and lonely place. The ‘university’ feeling of constantly being within arm’s reach of someone you know is not something London necessarily has to offer. Its sheer vastness makes the contained campus feeling impossible to create. Financial issues and the reality of an intimidating metropolis are not necessarily the direct triggers for feelings of anxiety or depression, but they certainly can buttress them.

The main problem is that issues related to mental health are often dumbed down and trivialised in social discourse. Specific and technical terminology relating to mental health is commonly used in the daily vernacular: many label their tendencies to be neat and clean as ‘OCD’, whilst others refer to their brief situational sadness as a state of ‘depression.’ Even the use of the word ‘retarded’ to denounce someone as stupid overlooks an issue that is both complex and sensitive beyond the comprehension of many. The cruel realities of social media and the external pressure to act a certain way have helped contribute to these simplifications. Whilst we now live in a society where physical disabilities aren’t ridiculed, mental health is still dismissed as a peripheral issue. A further understanding is desperately needed if we want that same society to treat everyone with impairments as equal to those without.

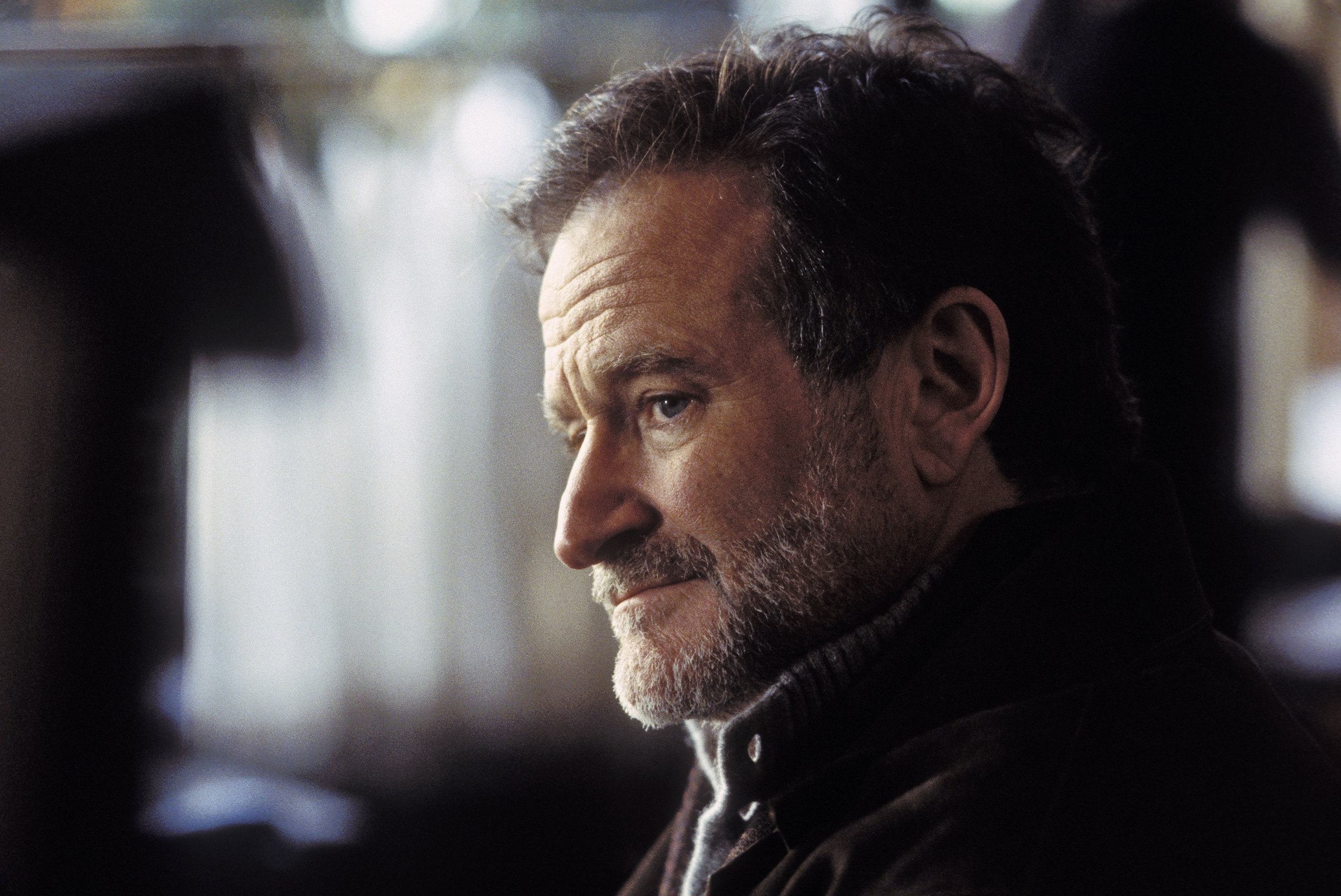

It is often (although not always) the case that sufferers are the ones who are perceived as the most creative and happy. Their spark of life they so often display in the public eye can be strangled and muffled behind closed doors. The death of the indescribable Robin Williams in August last year led many to question why a man of such talent, wealth, and joie de vivre would be depressed to the point where he would take his own life. It is for this reason that significantly more effort needs to be made in order to understand the issue: mental health problems do not follow the basic logic of ‘cause and effect’. Wider society must realise that having a mental disorder is not a choice; it’s also neither a weakness nor a type of vulnerability that sufferers need to “get over”. Rather, it is a disease, like cancer or pneumonia, and needs to be treated as such, especially for those struggling to adjust to the fast-paced life that living in our city entails. Telling someone to make the effort to overcome their mental problem is equally as useless as telling someone with a broken leg that all they need to do is change their mind-set. These false assumptions are dangerous; they lead to victims feeling isolated and stigmatised rather than feeling like they can seek help.

The reality of mental health is, and always has been, a serious problem. For sufferers it will often feel as though today is just another awful black day and that tomorrow is, and will forever be, an intangible reality. There will be flash points where they resent everything and everyone: the complacent, the thousands of successful suits they encounter everyday on the Northern line, and the perceivably happy. Denying these problems exist, and simultaneously denying their complexity and gravity, will help neither the sufferer nor society. And whilst for the sufferer a mental health problem is enormously difficult to overcome, for society, our ignorance about it shouldn’t be. It’s long overdue.