NATASHA POLOMSKI, a member of Demilitarise UCL, shares her views on UCL’s associations with the global arms trade, in an extended thought piece.

The arms trade

One of the narratives used to justify large-scale government support for the arms trade is the security and safety it provides. Yet the international trade of weapons is one of the most corrupt and security-damaging businesses around. The claim that the arms industry is driven by security concerns is probably one of the most prominent myths which helps to sustain it. Far beyond the reach of this article, it is important to note that the global arms trade intersects with multiple social justice issues, whether it be climate change, resource exploitation, poverty, immigration – the list goes on. Fundamentally, while little understood or even considered by the wider public, it is one of the most blatant manifestations of an economic system which puts corporate profits over livelihoods and sustainability. As Siana Bangura says in Campaign Against the Arms Trade’s People Not War zine:

‘The struggle against the arms trade must be anti-racist, anti-capitalist, antipatriarchal, pro environmental justice and actively centering those most directly affected by its devasating consequences… when we say People Not War, we mean people over profit, over hyper-capitalist pursuits and gains that oppress and kill.’

Corruption

Large amounts of public funds are often wasted on investment in weapons projects. Such projects are often tied up in corruption and bribery (the arms trade accounts for around 40% of corruption in global trade); they also frequently result in cost overruns which drain excesses of money whilst offering little technological improvement. One oft-repeated example is the F-35 ‘Boondoggle’: running at a cost of over US$1.5 trillion, the design suffered from so many technical problems that it had to be modified repeatedly, yet provided very little advantage to existing technologies. On the issue of public funds, it is generally the case that despite receiving significant subsidies from the public, arms companies spend billions on lobbying governments to buy their weapons. Five of the largest companies, including Lockheed Martin, Raytheon and General Dynamics, spent US$60 million on lobbying in just one year in 2020. Many companies rely on bribery and illegal inducements to incentivise politicians to buy their weapons, and many politicians have close links with arms dealers, often leading them to put corporate profits ahead of national and public interests. A significant number of contracts awarded are thus not done so based on security needs – creating environments of corruption which, in many cases, have actually weakened state security, despite excessive military spending (again, see Project Indefensible).

Militarism

It has long been argued by campaigners that government investment in weapons detracts funding from other social needs, like healthcare, pandemic risks, or dealing with climate change. It also leads to rigid views of security, predicated on militaristic thinking and incapable of seeing beyond it. In his 2009 publication ‘The No-Nonsense Guide to the Arms Trade’, Nicholas Gilby notes that in 2009, four of the countries on the UN Security Council – supposedly to help maintain peace and security – accounted for 79% of all arms transfers over a period of five years. The issue of militarism is currently a key problem in the UK, having suffered multiple crises after its incompetence in dealing with Covid-19. Despite its unpreparedness for climate change or non-military threats to security, the UK has invested over £16 billion into defence spending, whilst making cuts to NHS nurses’ wages, drastically reducing aid funding, alongside its pitiful investments into education recovery during the pandemic. This is a reality that the current government’s own MPs have criticised. It was also revealed last year that £1 billion of UK taxpayers’ money is being spent on the use of British-made weapons in foreign countries. The government is prioritising weapons spending over health and public services, and ultimately over our long-term stability.

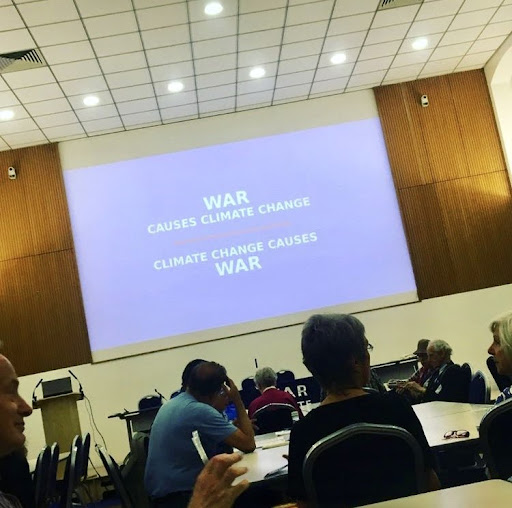

Militarism is a significant contributor to climate change and ecological destruction. The US Department of Defence, which is British multinational arms company BAE System’s largest customer, is the world’s largest institutional user of petroleum and the single largest institutional producer of greenhouse gas emissions in the world. If the Pentagon was a country, its fuel usage alone would make it the 47th largest emitter of greenhouse gases in the world. Crucially, investment on military ‘solutions’ simply draws funds away from effective diplomacy and efforts at conflict resolution, and actually tends to exacerbate problems of terrorism (research done by the RAND corporation in 2008 found that only 7% of terrorist groups have been effectively dealt with through military campaigns). Furthermore, it is evident that external involvement in wars through weapons sales and other military support merely worsens the situation – extending the conflict and increasing casualties. A prime example of this is the Syrian war, as well as the conflict in Yemen which has now wreaked havoc for over six years.

Effectively, this trade isn’t making anyone safer. It’s actually making us less safe.

The trade does, however, appear to dramatically increase the wealth and power of those profiting, who enjoy excesses of political influence through what is known as the ‘revolving door’ between arms companies and governments. It also maintains the UK’s position as an imperial and global military power by helping to uphold oppressive regimes and securing access to their resources.

Human rights and borders

Unsurprisingly, many of the weapons and technologies produced by arms companies are used to facilitate repression and international war crimes all over the world. In the 1990s, for example, BAE manufactured the weapons used to facilitate genocidal repression by Indonesia in East Timor; their F-16 fighter jets and protector drones have been repeatedly used against Palestinians to enforce illegal blockades on Gaza, and their armoured vehicles were used in 2011 in the repression of democracy protests in Bahrain. BAE have made over £15 billion through their involvement in the Saudi coalition’s attacks on Yemen, resulting in a humanitarian crisis in which 80% of the population are in need of humanitarian aid.

Many companies not only profit from selling weapons that fuel conflict, repression and asylum seeking, but also profit from producing technologies and warships which facilitate the policing of increasingly militarised borders that keep migrants out. Thales, for example, supplies maritime surveillance systems, which produced drones and research systems for tracking and controlling refugees, alongside its peers Airbus and Leonardo, which supply helicopters and drones for EU border security.

What has UCL got to do with it?

Research has shown that British universities and schools are becoming increasingly linked with arms companies. While UCL formally divested in response to DisarmUCL’s campaign in 2009, it still has other connections. In 2015-2018, Freedom of Information requests revealed that UCL received over £1.5 million in research funding from controversial arms companies, alongside over £5 million from the Ministry of Defense during the same period. UCL is directly tied to big names including both BAE Systems and Lockheed Martin. FOI requests have revealed that between 2018-2021, UCL received over £1.4 million in research funding, and over £48,000 in studentship and graduate degree funding. During this period, UCL paid over £540,000 in consultancy fees to a list of arms companies including BAE systems and General Dynamics – both of which sell weapons to Israel, despite the ongoing persecution of Palestinians through apartheid, along with Lockheed Martin. Many of the details are withheld under Section 43(2) of the Freedom of Information Act: a commercial interest exemption which allows information to be protected from the usual legal requirements of disclosure on the basis that its disclosure would be likely to prejudice commercial interests of the persons or companies involved.

The Centre for Ethics and Law

It was, then, extremely concerning to us that UCL’s Centre for Ethics and Law – a centre dedicated to exploring the relationships between ethics, law, and business – was, up until recently, sponsored by BAE Systems. The centre claims to ‘encourage ethical reflection, awareness and positive change through teaching, research and stakeholder engagement’. Yet in addition to its record of political influence and corruption scandals, BAE has a long record of involvement in human rights abuses. Most recently, over 6,000 members of its workforce have been stationed in Saudi Arabia to provide operational and logistical support towards a campaign known to target civilians in hospitals, markets, funerals, school buses and water facilities. Such war crimes are a pressing issue that we believe must be acted on immediately. Despite being a persistent human rights abuser, Saudi Arabia is BAE’s third largest customer. The company also operates by enforcing non-disclosure agreements and bribing its staff in order to keep corruption hidden. With BAE’s long track record of corruption and its dependence on insecurity, conflict, and climate degradation for its profits, it seems clear to us that no university should be associated with such an organisation.

Demilitarise UCL and London Students for Yemen recently distributed a petition against this to university staff and students. Since then UCL has given a statement confirming that ‘The Centre for Ethics and Law at UCL no longer has any sponsorship agreements in place, so does not receive any funding from sponsors’. A further FOI request has confirmed that this is subject to an ongoing review of the Centre’s sponsorship and funding strategy, taking place over the next academic year.

Research and studentships at UCL

However, the sponsorship was not, and is not the only connection that UCL has to the company, or the industry in general. Arms companies rely on research done at universities, and are dependent on hiring graduates to keep their businesses going. Funding graduate programmes and studentships seems to be a strategic way for them to make themselves seem appealing. BAE Systems is involved in several engineering programmes, including by funding bursaries for the MSc in Mechanical Engineering and funding an MSc in Power Systems Engineering and a PhD Studentship in diamond-based beta-voltaic. It also sits on UCL’s Industrial Advisory Board. We believe that this ultimately serves to both normalise and greenwash carbon-intensive and fundamentally unethical corporations which profit from war. We also searched the Engineering for Physical Sciences Research Council grant portfolio and found that UCL is listed as a partner with arms companies in research programmes worth over £50 million.

A UCL spokesperson was contacted regarding this issue and said: ‘Funding and sponsorship from external bodies are essential if we are to carry out vital research, helping us solve some of the most pressing challenges facing the world today, and ensuring excellence in both our teaching and student experience.’ They assured us that they are ‘committed to having the highest standards of research integrity across all activities and carefully consider all opportunities to ensure they are in line with UCL’s research funding ethics policy and consistent with its mission and values.’ Considering that their research policy includes a commitment to ‘respect for human rights, and countering ignorance, poverty, ill-health and political tyranny’: it is unclear to us how BAE, or any other arms company, meet this criteria or how decision-making processes regarding research partnerships are being conducted in order to ensure commitment.

The spokesperson also affirmed that ‘all donations, grants and sponsorship are subject to regular review and our research is entirely independent and academically driven’ – but given the extent of the research being done in partnership with companies who seek to profit from war, and the historical research done by Scientists for Global Responsibility (and others) on the role of the military and arms companies in seeking to influence education, it seems evident to us that such a statement is not empirically justified.

Moving forward in demilitarising education

Ultimately, these revelations appear to only just scratch the surface – and we intend to do more to find out the full extent of the arms industry’s ties with our university. Demilitarise UCL believe it is crucial that students are made aware of how these companies operate, and that all universities offer full transparency in their dealings with them. UCL relies on our funds as students, and it is our right to know where our money is from and what our institution is involved in. UCL prides itself on being disruptive, challenging the status quo and driving sustainability, and claims to be committed to decolonisation; it is, therefore, arguably indefensible that UCL should have such close ties with a trade which does everything to undermine peace and sustainability, through its dependence on imperial wars, corruption, militarism, and ecological destruction. The movement to move arms companies off campus is ultimately a small but vital part of wider efforts which seek to create a more just and sustainable world.

Our petition to put an end to BAE’s sponsorship of UCL’s Centre for Ethics and Law can be found here, and you can contact us on Instagram here to follow our work, find out more information, or get involved. You can also help to raise the issue as an individual through the Student Union, in your groups and societies, or directly to your heads of department, lecturers, etc. For more information, check out Project Indefensible, The Shadow World, and CAAT.

For specific issues raised here, follow our friends at London Students for Yemen to learn more about the crisis, and if you want to support the BDS movement for Palestine, you can use this template to email the UCL Provost, Dr Michael Spence.

You can also follow Demilitarise Education for updates on wider demilitarisation campaigns and peace activism. The movement to demilitarise education is fundamentally about transforming our universities so that they are not beholden to corporate profits complicit in destruction and exploitation, but rather serve the true aims of education in cultivating critical thinkers ready to take on the real security challenges we face today.

Featured image source: Creative Commons.