WILL FERREIRA DYKE considers how the experience of viewing art will have changed in a post-Covid world.

As lockdown begins to ease, art galleries and museums are gradually reopening as of July 4th. At last our artistic thirst can be quenched once again, although I expect the flavour of the beverage will have changed substantially. Commercial galleries, such as London’s White Cube, were given the go ahead to re-open from June 15th, the justification for this articulated bluntly by Jonathan Jones: ‘it’s capitalism, baby!’. Boris Johnson has allowed cultural consumption to continue, not for art’s sake, but rather to encourage the flow of money. This highlights the extreme lengths by which the art sphere is led by capital, an irksome relationship I cannot help but hate.

And while I am delighted that these institutions will soon open their doors, I still fear the impact a second wave may have on our beloved NHS. Social distancing measures in galleries and museums will have to comply with medical guidance: capped visitor numbers, the requirement to follow predetermined routes, and likely mandatory face masks. I wonder to what degree our engagement with public art and exhibition spaces will be altered by these restrictions, and what this will mean for the future of Britain’s visual culture.

Back in March (which, in my current disorientated conception of time, seems to have been some years ago), I visited the National Portrait Gallery’s David Hockney: Drawing from Life exhibition. I remember being gloriously hungover. Following a few too many tequilas and a late night gallivant to The Court, I thought that Hockney would be the best hangover cure. I was not whole-heartedly wrong. As I had done many times before, I fell in love with Hockney’s masterful hand and graphic images. I felt a particular affinity to his watercolour self-portrait; seated and reading a book on a lonesome chair. I fear that I appreciated this image as it in some way mirrors, or even encapsulates my own persona: a glasses-wearing loner.

The exhibition as a whole was enjoyable and felt easy to appreciate without too much engagement with individual pieces being required on my part (potentially, however, this assessment was a result of my alcohol infused weariness). Regardless, the digestible nature of the work made it accessible despite the small scale of the exhibition space contrasting with the alarmingly high number of visitors. Pre Covid-19, times were wild! In light of changed rules and guidance, I have begun to reflect on how I would have engaged with and perceived the works today. Would I have taken away more if I was left to observe the art in a calmer space with specified visitor quantities?

In this thought I can find an exceptionally small silver lining in living through a time of a global pandemic: exhibition loneliness. With lower visitor numbers, the new exhibition atmosphere may now be calmer and more conducive to art-viewing than that of a ‘pre-Covid’ experience. This would allow for additional time and space to reflect on works which we may not have previously dwelled upon. However, this luxury may well be tinged also; exhibitions may have to implement time limits, allowing for a steady visitor flow to prevent excessive queueing. Thus, there may be limits to artistic consumption, this restricted viewing format adding a certain pressure to one’s visual digestion. The thought of roaming around a gallery in a somewhat singular state is one of fantasies, a cinematic utopianism, and a state which I blissfully idealise. Though the realities of it may be far less pleasurable.

For many, gallery trips are also a social affair, a way to fill weekends with culture and an overpriced café. I too enjoy a communal gallery experience, thriving off of the conversations that art provokes as a way of understanding alternative readings. Similarly, the process of verbalising ideas and thoughts can generate a deeper understanding of a work. Thus, with a limited visitor capacity and time frame, one’s consumption and emotional appreciation of art may be restricted to the point of surface level engagement. That being said, it seems not all exhibitions require such lengthy pondering; suffice to say that for Hockney, additional time was not needed. Though companionship certainly was, if not simply to vocalise the museum labels and captions through my regretful haziness.

Beyond fearing a different personal gallery experience, I find myself asking several questions as to how accessible art will become on a much broader scale. How likely is it that swathes of the general public will be blocking out Saturdays for leisurely museum visits? Will the decrease in visitor numbers lead to significant economic losses for our major art institutions? Could this consequently lead to admission charges being added to our most celebrated free establishments? Will temporary exhibitions prices be further hacked up?

My fears are not completely reliant on capital, but are also rooted in cultural and social anxieties about arts education. Think back to Steve McQueen’s Year 3 installation at the Tate Britain, an embodiment of London’s youth. It’s sprawling tube and billboard coverage allowed outsiders to be presented with the art outside of the walls of the gallery, encouraging further visiting. McQueen’s initiative encouraged students to view themselves within the institution, allowing them to literally see their belonging in art-spaces. The potential hindering of such engagement may be detrimental not only on an induvial basis, but nationally for our future creative generations.

Art needs physical, in-person engagement. In my opinion, the sensuality of an artwork cannot be fully felt through mediated outlets such as computer screens or broadsheets. I am excited about the gradual reopening of galleries and am counting down the days to be reunited with the V&A and Tate. Although, I still question how this revised experience will be on a personal level, and how the wider cultural engagement with art will pan out during our current climate. I remain hopeful that this new experience will none the less be pleasurable, and that institutions and creative masterpieces are ascendant over the clutches of coronavirus. If not, I now hope to view Hockney hammered, not hungover – mitigating the changes.

London Gallery reopening dates (subject to change):

- Tate Britain and Modern: July 27th

- The National Gallery: July 8th

- Royal Academy of Arts: July 9th-12th (for Friends of RA) and July 16th for pubic

- National Portrait Gallery: not reopening until 2023 for a £35.5m redevelopment

- Barbican Art Gallery: July 13th

- Serpentine Gallery: August 4th

- Saatchi: remains closed until further notice

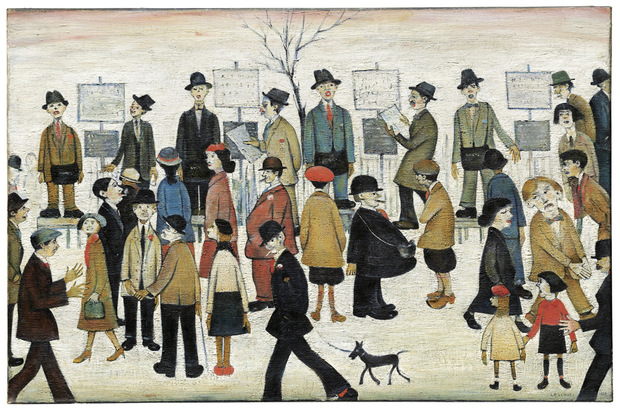

Featured image: Laurence Stephen Lowry’s A Northern Race Meeting, 1956, oil on canvas. Image courtesy of Christies.com.