NICK FERRIS examines the documentaries programme at London’s Russian Film Week.

When attending Russian Film Week, one would hope to encounter new and honest insights into Russian society, culture and politics. This is London, not Moscow, so what’s on show should not be seriously hampered by censorship laws or state influence. Yet when I attended the RFW documentaries programme last December, one film after another felt tinged with propaganda.

Mockumentary Vladivostok Vacation portrays the exploits of Siberian rock band ‘Mumiy Troll’ aiming to make it big in America. Presented as a series of animations, episodes and interviews featuring band members and their associates (think teary old drunk Russian grandmothers and local Mafioso ship-owners being fawned upon by prostitutes) the film comically expresses contradictory feelings of love and frustration at living in a Russian city as unique and remote as Vladivostok. The film’s tone is predominantly self-deprecating, light-heartedly mocking traditional Russian pride and prestige with images of decaying Soviet symbols and frequent allusions to ‘Mother Russia’. Yet, while this may seem like self-criticism, the rosy tint that permeated nearly every scene means that the film’s jesting message never reaches the point of subversion.

Still from ‘Vladivostok Vacation’

The band does eventually embark upon their world tour, with an enterprising sea captain who promises ‘I’ll take you anywhere’. Yet ‘anywhere’ inevitably transpires to exclude their favoured first port of call, the USA. If the film has a message, it is a reaffirmation of the classic conflict between Western and Eastern ideologies, which supposedly makes the two entities of Russian rock music and American aspirations completely incompatible. We see the band travel to China, Singapore, Korea and South Africa. These countries are portrayed through an orientalist lens, with temples, farms and old-fashioned cultures galore. There is no hint of globalisation; the filmmakers seem unable to escape their ingrained sense of Russian tradition, incapable to perceive the realities of the modern world. Eventually, ‘Mumiy Troll’ make it to the USA, though at this point the film rather digresses into a confusion of random pop-art animations and attempted interviews with drunken sailors. Their manager, ‘Mr Spoon’, somehow takes advantage of his band’s music to end up alone in Los Angeles with an American wife, a Grammy, and a mansion. The band, now disillusioned and choosing to live the honest life back in Vladivostok, manage to find sizeable success back home. The message is clear: if you look for success in America, you will either fail or be corrupted by individualistic, capitalist greed; true Russians must adopt a love for their country in spite of her problems, and happiness and success will then follow.

Still from ‘Roentgenizdat’

Despite its faults, Vladivostok Vacation remains a credible film with humorous and energy-charged moments. The same cannot be said of the next film, Peterhof: Eternal Paradise, which is so insufferably dull it seems like a satire of every bad documentary ever made… It dedicates half an hour of motion sickness-inducing moving shots to the Peterhof palace from every camera angle possible, all to relentless Russian classical music. This is not a film; more of an advert, though of such poor quality that it is more likely to trigger laughs than cultural interest. Without fail, it manages to re-iterate Vladivostok Vacation’s message of East-West incompatibility. Judging by the amount of people who left the cinema during the screening, the so-called ‘love letter to the beautiful palace of the Russian Tsars’ didn’t hold sway with a London audience.

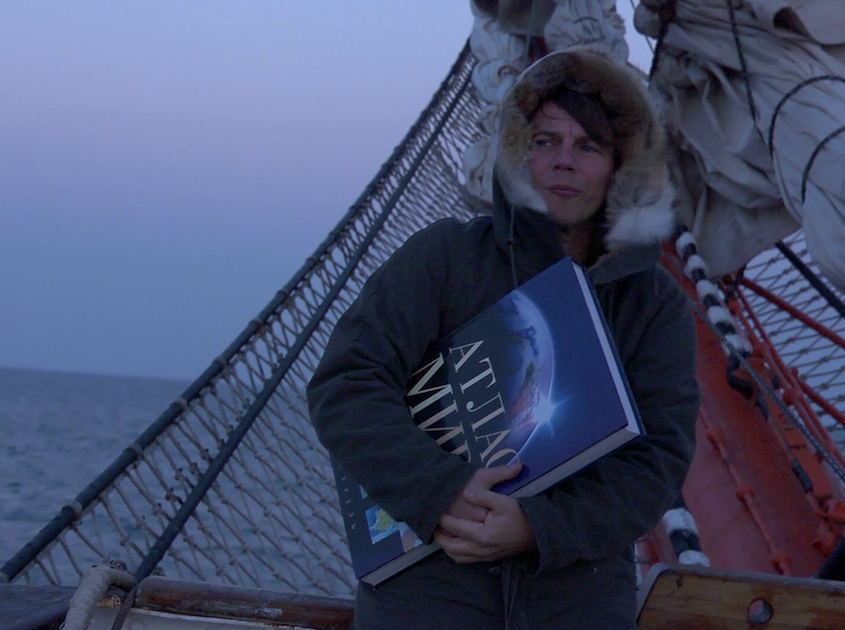

Still from ‘Roentgenizdat’

The final two documentaries seemed to tackle interesting subjects. Roentgenizdat told the remarkable story of an underground industry making vinyl records on old X-rays in Soviet cities in the 50s and 60s. Hardened old rebels revealed how recordings of ‘Little Richard’ and ‘The Beatles’ would circulate amongst their friends at the risk of several years in prison. Finally, Babel Village presented an artist in a village obsessed with community art projects. Past projects have included giant towers of hay, an odd-looking wicker basket, and a vast field of snowmen.While both films are certainly of infinitely higher quality than Peterhof, they are perhaps more BBC 4 than Russian Film Week. The films are essentially extended magazine features, with little sense of narrative and so perhaps do not really deserve a place at a film festival.

Both films also maintained a palpable sense of nostalgia. Roentgenizdat presents a quirky rebellion against cultural restrictions that are firmly those of the 50s and 60s, while Babel Village advocates a kind of socialist spirit that led everyone to work together to create communal art. While there is nothing ostensibly wrong with this kind of nostalgia, it ended up feeling like an agenda promoting different strands of a Russian traditionalism (that feels inherently anti-west), which helps Putin keep his high domestic approval rating. This was compounded by the moment I spied the monogram for the infamous Kremlin-funded news network Russia Today in the corner of Babel Village.

Still from ‘Babel Village’

I came away feeling predominantly frustrated at the filmmakers and organisers who seemed to be pushing an isolationist agenda that emphasised the continued incompatibility of East and West, rather than the need to build bridges. Such a message felt patronising to the London audience and also to Russians at home who are clearly capable of far more than these backwards-facing films would suggest. It was, too, a frustration at London: supposedly a centre of free speech and press, these films are indicative of those values bowing down to external financial and political might. All that is left: dullness.

The Russian Film Week’s documentaries programme was screened at Regent Street Cinema on 4th December. More information here.

Feature image courtesy of rtd.rt.com