KAITLYN WHITE interviews author Imogen Edwards-Jones about her new novel.

The Witch’s Daughter is Imogen Edwards-Jones’ latest release, a historical novel which charts the evacuation of the imperial court from St Petersburg during the violent Russian Revolution. Following the release, I had the pleasure to meet Imogen for an interview: she was a dynamic conversationalist, eagerly dishing out anecdotes from her experiences in St Petersburg, including a haunted visit to the abandoned Znamenka Palace, from which she fled quickly, fearing the ghosts that lay within. Imogen is an enthusiast of Russian history, with years of experience studying in Ukraine and Russia and extensive knowledge of the Romanov court. As an avid researcher, she pays extreme attention to detail: in preparation for the novel, she undertook various travels and studied at the College of Psychic Studies in order to learn about the Black Princesses’ experiences with witchcraft and the occult, eager to fill in gaps in the archives of their lives.

Off the bat, it became clear that this was a difficult novel for Imogen to write, as it required delving into the horrors of the Russian Revolution. The text is permeated with the distressingly illustrated motif of refuge: Nadezhda, the titular protagonist, reluctant to flee her motherland, fills her pockets with handfuls of Russian soil in desperation to cling to her home. To evoke the horrors of the period, Imogen fills the novel with realistic accounts of the drastic conditions of the revolution. Imagine sprinting from riots, tripping over the defrosting dead bodies of executed pedestrians, and smelling months of sewage from burst pipes lining the streets as bullets rain down over you. This is the decomposing reality her characters must endure. She further explained that understanding the characters’ environment was essential to accurately capture their experiences, the consistent surrounding of death accounting for the popularity of the occult. Such a carefully constructed setting compels a strong sense of empathy in the reader, one that adds both to the sensation of lasting tragedy, and also the outrage at the irreverence of the royals, who cling to their luxury whilst riots take place in their front gardens.

Such paradoxical tensions remain prevalent throughout the story: the characters simultaneously love their country and are ashamed of its deterioration; they hunger to the point of starvation, yet save their remaining food for their spouses; they are overwhelmed by their pasts and hopeful for their futures. Militza, Nadezhda’s mother, is haunted by Rasputin following his murder, yet grateful that his death freed her family from his manipulation. Nadezhda, in turn, is preoccupied with the memory of Oleg, her lost love, whilst learning to love again with Prince Nicholas. Oleg’s accidental death by gangrene at the beginning of the novel symbolises the end of innocence and foreshadows the horrors to come. The underlying sense of love, maternity, and familial bonds adds a tender countercurrent of humanity to an otherwise wasteland of genocide and brutality.

I was eager to ask Imogen about her experience writing a historical novel and about the freedoms and limitations of the genre. From fact-checking nicknames, dates and locations to playing with conspiracy theories on the identity of Rasputin’s murderer, her writing process was indeed extensive and long, an undertaking that was easy to get lost in. She stressed the importance of balance: an author of historical fiction needs to know when to hold off on excessive amounts of factual information, and when to blend the historical truth with a cohesive literary narrative. As she explained, details in the story need to be believable, with transitions between the cinematic scenes being well-timed and realistic. The Witch’s Daughter achieves this well. The historical detail adds to the tension of the novel rather than giving it a feel of a textbook.

When asked about her favourite part of the novel, Imogen instantly expressed her sympathy for the charismatic character of Bertie Stopford, inspired by the historical figure of the same name. Bertie was a courteous English diplomat who smuggled the Grand Duchess’ jewels out of Russia and was later imprisoned for homosexuality. His lighthearted humour adds relief to the reader amongst the hardships in the plot. Drawing on Stopford’s little-known autobiography, The Witch’s Daughter includes a detailed insight into high-society soirées and the tumultuous reality of living in Petrograd as the rebellion spread. Like Bertie, Militza and Anastasia were also intriguing characters to Imogen due to the shortage of information about them in history books. The two sisters faced discrimination for their unnoble Montenegrin nationality, for being women, and for being a part of the doomed Romanov court. Bringing light to social castaways, the author stressed, was one of the driving forces behind her novel.

I concluded our conversation by asking Imogen the shameless question: ‘What advice do you have for aspiring writers?’ She laughed good-naturedly whilst petting her dog on her lap, who looked up at her with equal fixation as I did. Planting her eyes on the Zoom screen, her answers were unwavering: read the books you actually want to write. Read as much as you can, and practise even more. Underline what you like so you can nick that later on in your own work. And, most importantly, finish your novel before editing! Don’t start editing before you have a full draft because if you keep rewriting the same three pages, you will never have a novel. I laughed, thoroughly inspired, and eager to take on her advice, as I hope you are too.

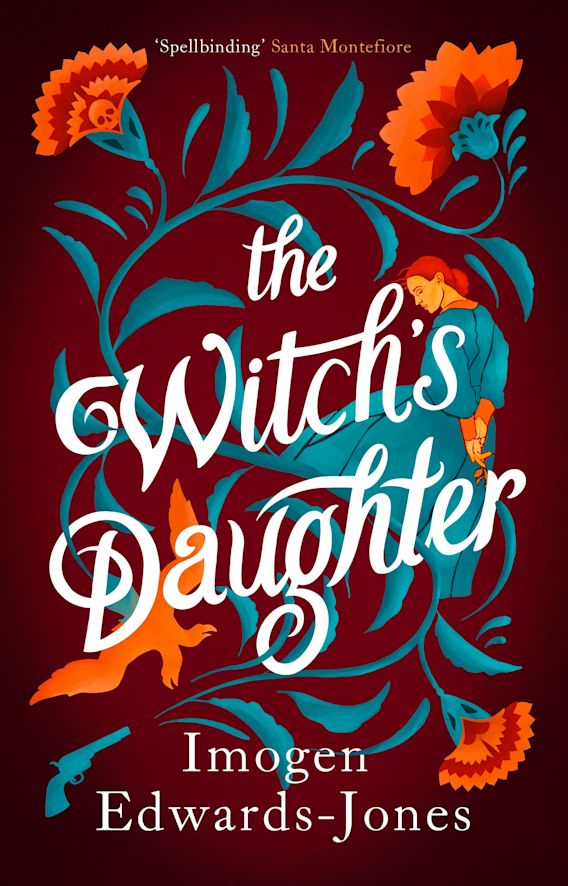

Featured image: Portrait of Nadezhda Petrovna, Princess of Russia, 1917 by Savely Abramovich Sorine. Source: Artnet.