EMILY DRIVER reports on the annual readings by shortlisted poets at the Southbank Centre.

Last Sunday’s T.S. Eliot Prize shortlist readings commenced as you’d expect any worthwhile party should, with ‘A Game of Chess’. I’m not sure, however, that T.S. Eliot was all too familiar with the ins and outs of the game when he used this title for the second section of his masterpiece poem, The Waste Land, as this kind of chess didn’t involve any pawns or bishops but mythical birds, couples bickering over nothing (quite literally), and a girly gossip, rudely interrupted by a pub owner telling them to hurry up and get out for closing time. While no kings were checkmated during the reading of this extract, the panel of judges who performed it—Paul Muldoon, Sasha Dugdale and Denise Saul—evocatively brought to life that quintessential human experience: not knowing when it’s time to finish your drink and go home. Tonight, however, we held onto our drinks as we followed ten poets ‘into the rose garden’, as Eliot would say, of the collections nominated for the 2023 prize with our host, Ian Macmillan. Each poet was given seven minutes to read a selection of poems from their nominated collection and, as Ian promised us, ‘help us make sense of the senseless’. Instructive and economical, what more could we ask for?

In case anybody got lost on their way, our first poet of the evening, Eiléan Ní Chuilleanáin, thoughtfully provided us with her fourth collection, The Map of the World. While you might not be able to sharpen up your knowledge of capital cities with this map, you will find a cluster of coruscating poems that catch past and present, the concrete and the mysterious, within the poet’s ‘nets of language’. I imagine Eiléan writing these poems much like a fisherman works, tossing the rod of her pen out over the sea of experience and hooking upon discrete moments of ‘light / that falls when there’s nobody there to see it’. The unattended moment, the one in and out of time, is the space where Eiléan works her best. The final poem she read for us, the poignant and plangent ‘War Time’, demonstrates this masterful stroke of vision in its final moments as fastens onto a young girl playing the piano in an empty church, the notes sinking ‘into time, / the time that’s lost, the note so much older / that the hand that conjures’.

Elevating certain moments out of the ordinary rhythms of experience is a skill that Eiléan evidently shares with her fellow Irish poet, Jane Clarke. Jane’s A Change in the Air was one of my personal favourite collections in this year’s shortlist, which might be best described as the poetic equivalent of a wind chime – registering and translating the subtle changes in the atmosphere into lyrical forms. Gliding us through Irish life, history and landscape down to the last drop of dew, Clarke’s language is spare and purged of stylistic ornamentation. Her poetic power is drawn from her carefully selected material, from which no shade of quality escapes her vision. Every throwaway comment, act of labour and simple gesture of Clarke’s poems is inflected with insight and human feeling so that even the simple act of two lovers sitting outside a while longer to listen to the ‘wood pigeon’s five note-tune’ in her exquisite love poem, ‘June’, becomes sanctified by the light of her attention.

In this day and age, the project of writing a genuine love poem like ‘June’ is no easy task, as Abigail Parry was to find out while working on her second collection, I Think We’re Alone Now. On stage, Abigail explained that she was given the intellectual exercise by her brothers to write a sincere love poem (and by this, she meant that they told her she was ‘categorically incapable of writing a love poem sincerely’). The moon and the stars aligned for Abigail as she read to us a poem that we can proudly hold up as evidence that romance is not dead in the 21st century: ‘The Brain of the Rat in Stereotactic Space’ – ah, that old romantic cliché. Abigail’s original, if not sincere, spin on the love poem was exemplary of her comedic intuition both on stage and in her collection. While we might not be printing it onto our Valentine’s Day cards, we should be picking up her collection for its quirky observations and her inventiveness when it comes to playing with language.

Animals being not quite where they belong turned out to be a common theme in this year’s shortlist for the prize. In Fran Lock’s thirteenth collection, Hyena!, she imagines herself as the four-legged predator prowling through the dream-like labyrinthine streets of London, using the hyena figure to explore and negotiate the intersections of animality, femininity, class, grief and trauma. Doing away with the straight-jacket of the human form, Fran’s shapeshifting persona strips away all veils of sentimentality and pretence to give rise to the strange poetic alchemy that forms when you let your inner hyena howl. Fran’s poems have a certain ravenous quality about them, and her readings were breathless and relentless, like a voice that had broken free from its constraints, documenting, detailing and consuming all of its surroundings.

While appearing to be more satisfied with the human form, Joe Varty’s debut collection, More Sky, similarly explores the surreal underbelly of trauma. Joe dedicated his readings to a friend who had recently passed away and with whom he had shared fond, fuzzy memories with at last year’s T.S. Eliot Prize readings after they had snuck in a bottle of pinot noir under their jackets. Accordingly, a tall, plastic cup of red accompanied Joe on stage this year, giving him the Dutch courage to read ‘The Children’, a poem he usually deemed ‘too depressing’ for public readings. Joe’s reading lit a lantern into the dark corners of masculinity, suicide and trauma, and we managed to come out the other end just about unscathed. Joe’s poetry is of a markedly different stock to the others which were shortlisted for the prize: informal, full of slang and cut from quirky material. ‘Dear Postie’ was the last poem he read out for us, inspired by the kind of notes he’d receive from houses when he worked as a postman. The series of instructions get more exuberant and self-revealing as they go on, flipping the ‘Do not’s’ back onto the speaker and their relationship with their alcoholic father. Dark yet urgent and necessary, Joe’s collection finds innovative routes for reckoning with personal disaster.

Speaking of instructions, Jamaican-born poet Ishion Hutchinson has a whole school of them. His dizzying third collection, School of Instructions, is dedicated to ‘the memory of those West Indian soldiers’ who volunteered to fight in the British army in the Middle East during World War One. With all the elevation and grandeur of a tragic chorus, Hutchinson’s reading went about narrating the terrors of war and naming the ‘forgotten lives’, bodying them forth out of silence and into presence. Hutchinson wrings rhetoric round the neck in lines such as ‘Wild butchery of souls in the desert’ and proceeds through swelling lists and heavy, percussive repetitions that reverberate like a grand litany, dragging the past out of the ‘mud’. Oracular and earthy, Hutchinson approaches language as an act of memorialisation, etching the dead into the deathless stone of poetry.

Jason Allen-Paissant’s collection, Self-Portrait as Othello, which went on to win the T.S. Eliot prize on Monday, also figures poetry as an art of re-animation. In this trailblazing work, it is the fictional character of Shakespeare’s Othello who is brought back to life as a template for exploring the inter-generational wound of colonial history as Jason braids together strands of poetic memoir and ekphrasis into a moving narrative of black male bodies in Europe. As the title of one of the poems Jason read out for us suggests, this is a work that holds one foot on absence and white space, ‘What Shakespeare Did Not Write About’, and the other firmly grounded in his extensive research of colonial history. Jason’s performance did justice to his tragic hero’s status as a consummate shapeshifter, leaning into the polyphonic medley of voice, different registers and languages contained in his poems with playfulness and ease. A profound celebration of multiplicity and eclecticism, it’s no surprise Jason’s collection took home the prize this year.

Another shape-shifting figure awaits at the entry-point of Kit Fan’s The Ink Cloud Reader in the form of the legendary Japanese artist Hokusai, who is said to have adopted over 30 pseudonyms in his lifetime and moved houses over 93 times. The disillusioned speaker of Kit’s first poem ‘Cumulonimbus’ seeks to overcome his midlife crisis in the only way that seems just, by being ‘struck by lightning / and survive it, like Hokusai’. Kit’s poems are drawn to creation that survives violence and art that emerges out of hostile conditions. The last poem he read for us, ‘Derek Jarman’s Garden’, is an alternately surreal and sublime description of the garden planted by the artist and gay rights activist Derek Jarman, just within sight of the Dungeness nuclear power plant. Opening with a subversive re-echoing of Emily Dickinson—‘You dwelt in impossibility’—the poem commemorates the survival of art and nature against all rhyme and reason.

The shortlisted poets seemingly can’t get enough of Emily Dickinson this year as her influence also looms over the fiery lyrics in Sharon Olds’s latest collection, Balladz. Sharon has repeatedly proved herself to be a powerhouse of contemporary poetry, previously winning both the T.S. Eliot Prize and the Pulitzer Prize for her 2012 collection Stag’s Leap, and, I would argue, is one of today’s greatest living poets. Balladz, her thirteenth collection, has all of her signature aggressive intimacy and imaginative sincerity, approaching the subjects of quarantine, ageing and the body, and reminding us of how poetry might indeed be ‘a fairer house than prose’, as Emily Dickinson would say. While she was unable to attend the readings on Sunday, her absence was soon filled by the laughter poems such as ‘Quarantine Morning’ had us in. Funny and macabre, Olds opens the poem by asking, ‘how much difference is there, anymore / between me and a cadaver?’ and ends the poem with a triumphant orgasm death. If I had to guess, I might tell Sharon that I don’t think a cadaver can orgasm. In the 80’s, Helen Vendler dismissed Olds’ poems as ‘pornographic’, and it’s good to see that over 30 years later, she still couldn’t care less.

Nor did our final shortlisted poet of the evening, Katie Farris, shy away from encounters with sex and death. Katie’s debut collection, Standing in the Forest of Being Alive, is deeply personal, written at a pace with her breast cancer treatment, having been diagnosed in 2020. Like Olds, Farris’s collection teaches us how to write about what’s happening to the body as it alters and changes, and how to ‘train [oneself] to find in the midst of hell / what isn’t hell’, as ‘Why write Love Poetry in a Burning World’ elegantly puts it. Moments of happiness, hope, tenderness and comedy remain buoyant in Farris’s poems amidst a sea of disaster, whether it be her cat leaving its whiskers on the floor ‘In solidarity with my chemotherapy’, or reminiscing on a chair so perfect for lovemaking that she ought to have taken it from her friend’s house. In this rolling poetic autobiography, Farris uses poetry as an alternative kind of balm for the wounds of life, and offers it to us as medicine for our own troubles.

Such were the fragments of life that the judges had shored up for the shortlist for the 2023 T. S. Eliot Prize. At one point in the evening, our host Ian Macmillan said that encountering a good poem is like getting a stain on your clothing that you can’t quite rub off. I wish he would’ve told me that before I wore my favourite coat to the event last Sunday. However, I was delighted to see that Jason Allen-Paissant’s collection, Self-Portrait of Othello took home the 2023 prize on Monday—a must-read for Shakespearians and non-Shakespearians alike.

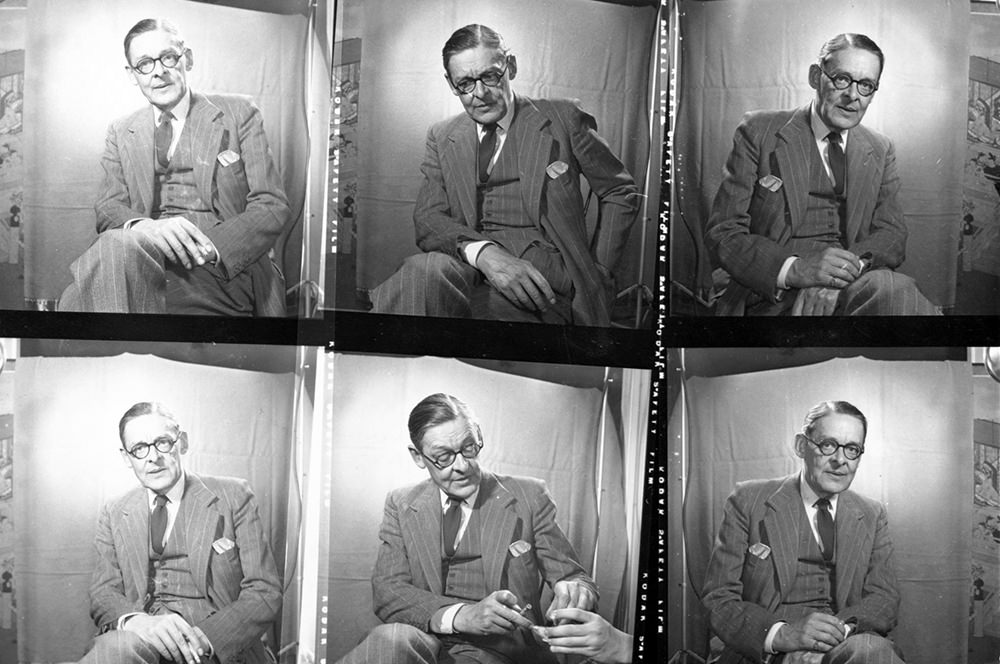

Featured image: T. S. Eliot. Contact sheet for a portrait taken by Harris J. Sobin, at Harvard, 1952. Source: tseliot.com.