JESSICA PENG explores her love affair with Montgomery’s Anne of Green Gables.

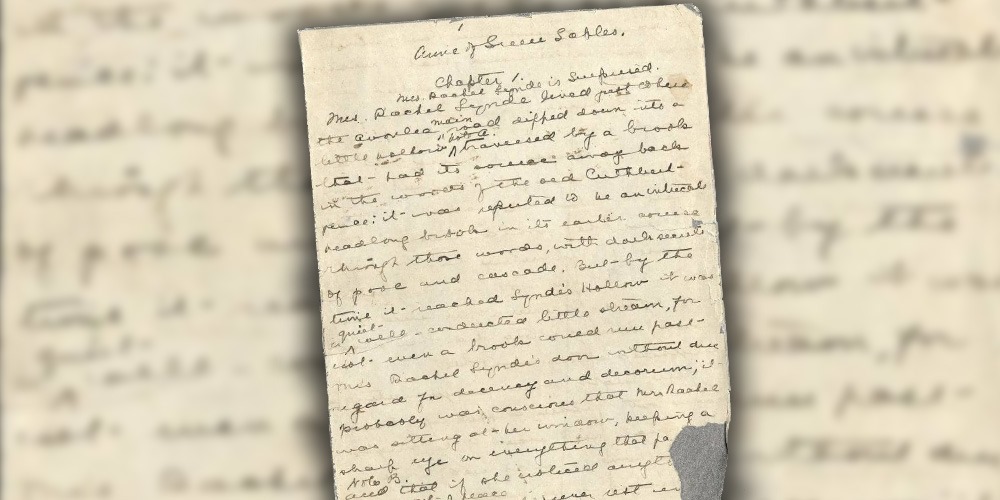

A love story demands a beginning, so let me paint you a scene. I am eight years old and it is evening. My family and I are in the living room, occupied with separate tasks. Mine happens to be crying over a book. My family are either mercifully pretending not to see, or my hair-covering-face tactic actually works. At any rate, this is the first time I will read Anne of Green Gables by Lucy Maud Montgomery, and as Marlowe said, whoever loved that loved not at first sight?

Before you ask: no, I have not seen the films, nor the recent Netflix adaptation. This is not out of snobbery. I am simply not interested in them, and neither do I need them. Anne of Green Gables was introduced to me as a novel and I loved it because it was written down. I loved wondering what on earth puffed sleeves were and the dreamy hue that was ‘soft brown gloria’. I loved imagining Anne’s carrot red hair, sometimes green. The book came alive in my mind and stayed there, existing as something I’d read, something I’d helped create. Since the first time, Anne’s been a rewritten memory in my head. I can’t recognise it as anything else.

This frankly alarming possessiveness is not the simple elitism of a book purist. Soon after finishing it, I recommended Anne to some friends, who were only a little judgemental that I loved a very old book with a weird stain on the cover. My friend Greta actually did read it, though she said she skipped the first hundred pages because they were ‘boring’. This throwaway comment lodged itself into my small, sensitive soul, and I made a vow to never recommend anything to anyone ever again, as they would never approach my literary loves with the patient, reverent awe they deserved. Too young to understand these bizarre emotions, I insisted to Greta that she’d missed out on all the vital scene-setting of Mrs. Rachel Lynde and Avonlea life that occurred in the first hundred pages. Greta responded by saying her way made the book more enjoyable. Naturally the mere suggestion that any part of Anne of Green Gables wasn’t enjoyable was pure sacrilege, and I’m not sure I ever forgave her. We haven’t spoken in years.

Another incident occurred a few years later, when I was about thirteen. With braces, bad glasses and a face I’d like to forget, I assessed the situation and decided I didn’t value looks anyway. To prove my point, I read a lot, so luckily something always covered my face. Another friend (who I have also since dropped) remarked on the book I took proudly out of my bag: “Someone once told me I’m a lot like Anne.” This was another dagger in the heart.

Ellie was tall, red-haired, white, slightly kooky. She hadn’t even read Anne of Green Gables, but the score was clear. I was small, dark-haired, Chinese, with a personality that lurched between deeply sarcastic and easily hysterical. I knew Anne, and I also knew that a casting director would pick Ellie over me. The thought hurt, and I buried it away.

This is not a personal essay on identity and the struggles of growing up with only white role models. Anne is admittedly something of a questionable role model herself. I dredge up that painful memory merely to illustrate that I have, and probably always will have, a deep, personal attachment to Anne of Green Gables, the kind of attachment only rather lonely children are capable of forming with fictional worlds, which never disappoint, which never go away. I can’t bear anyone being closer to the book than me, and Ellie’s superficial closeness really stung. Love inevitably borders on possession – to love something is to allow it into you, to become a part of you. But I was dismayed to find that my love was also, apparently, a refusal to admit the failings of the beloved – a sort of wilfully blind, despicably parental, misplaced worship.

Look, I’m an English student. A good deal of the time, reading for enjoyment overlaps with reading critically. I don’t believe criticism destroys enjoyment: on the contrary, it enhances it. Yet I still reacted so badly to Greta’s criticism of Anne (‘boring’), and I don’t even think I can blame that on me being eight, or her being wrong. When I applied to university two years ago I read a book of critical essays about Anne, and I hated every single one of them. They were breaking my Anne down, fishing through the book for clues that matched up to their useless little theses on whatever, and thinking that they’d uncovered some dazzling truth about the book, when I knew that I was closer to it than any of their contrived essays were. These critics were combing through the book, but there wasn’t a sense that they really knew, really felt the experience of reading Anne. They liked it because it was a popular children’s book that had ostensibly lived on. But they didn’t love it. There was no sense that the book was specifically important to them, and that the experience of reading Anne had affected them in any meaningful way. And without love, what did these critics, these academics know? Only what they wanted to. They were just using Anne. I was different; I loved Anne.

I know the conclusion you will all have drawn by now, but I assure you I am not insane. Actually, the last time I read Anne of Green Gables was about two years ago. Since I know there are people who read Harry Potter every year, it is clear that there are those out there more obsessed, and with poorer taste, than me. If there were an Anne of Green Gables theme park, I would not go—or at least, I would go ironically. I own zero Anne-related memorabilia; I do not plan on giving my children Anne-related names; I am not obsessed with any particular character. I am not retreating away from the real world, or romanticising fin de siècle small town Canada, or yearning for the simpler time of childhood. I am simply enamoured of the book.

However, I can safely say that Greta did not love Anne, and perhaps I was so revulsed by her pithy criticism because it didn’t come from a place of love, but from impatience. Similarly, I hate a critical essay that breaks Anne up and serves up the pieces, boasting that it’s uncovered a ‘truth’ in her through its battering analysis. ‘Anne of Green Gables is attractive because it is a story of an orphan girl who finds a home…’ Yes, fine — this is true. But why do we always have to be breaking things down to understand them? Don’t we then end up with a load of pieces—‘finding a home! Bildungsroman! nostalgia! charm!’—which tell you nothing about the experience of reading Anne, and in fact splinter it into a list of literary ingredients? It’s like baking a cake without mixing it together. And if this is the case, if we can’t get through to a text in this way, then what does—or should—criticism do?

Oscar Wilde wrote that criticism is not as much about the art as we think, but rather it ‘treats the work of art simply as a starting-point for a new creation’. Critical writing might have a life independent of the art it criticises; it might draw from places beyond the work; it might seek to enrich rather than dissect. Wilde quotes Walter Pater’s study of the Renaissance and argues that we don’t read Walter Pater to learn about the Renaissance; we read Walter Pater for Walter Pater. If I asked you to describe a book, movie or TV show you loved, I’d be disappointed if you told me where it was set and the names of the characters. The things we love don’t exist in our head as faithful renditions of facts. They exist as feelings and memories. For me, reading Anne is loving Anne. My experience of the book isn’t just the story it contains, but also the story I have tried to tell in this article, starting from me as a child in my living room, pretending not to cry. I said that love was possession, but actually it’s better. It’s renewal and recreation, making an experience out of reading that is bigger than the book itself.

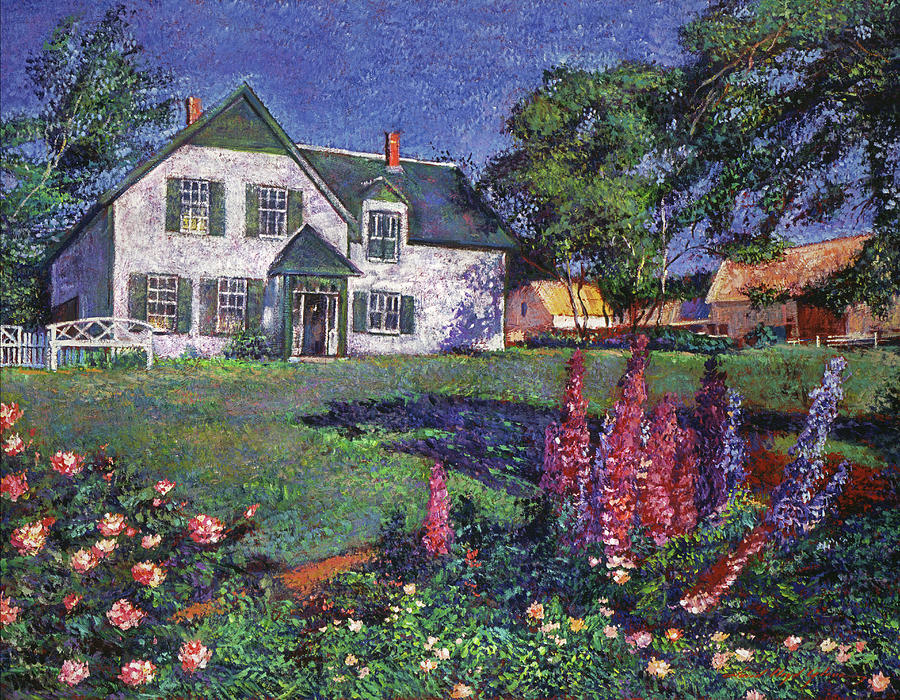

Of course I urge everyone to go and read Anne, but as I said, I was eight when I first read it. The novel is brilliantly self-aware: Anne’s infamous imagination has her play-acting Arthurian myth and wishing her life was more romantic, when of course for us, Anne’s world is a quaint, faded picture of idyllic, bucolic Canadian life, where everybody knows everybody and people drive in buggies to see concerts at the nearest big city. But it is still a children’s novel, wrapped in a small world and (largely) dominated by small concerns. Adults might find it claustrophobic, or worse, irrelevant.

Montgomery knew the gains and losses of growing up. There are eight official novels featuring Anne (and two loosely-connected spin-offs) but the first is by far the most popular. Anne’s magnetism is protected by her youth and fictionality: as she gets older and goes out into the world in the sequels, she becomes more ‘real’, domesticated, concerned with moving house and her children’s health. The more Montgomery wrote, the more she knew that time was slowly draining Anne of her magic. Thank God I read Anne of Green Gables aged eight and not any later. Childhood is a special time, and if Anne and I had met later, we wouldn’t have connected the way we did.

There is a feeling among ‘clever’ literary people that ‘love’ is not a suitable reaction to literature. Criticism centres around being provocative, new, enlightening, complex. Love is silly and unthoughtful. Sharp, intelligent readers are too clever to love; or they love, with embarrassment, and mitigate it with analysis. But I think that’s ridiculous. I know there is something in Anne worthy of analysis because I love it. Love is not an uneducated, incoherent response to a work of literature. It is a conviction and the reason for all the work we do.

For years I have talked to anyone who’ll listen about how much Anne of Green Gables changed my life, but why should they have believed me when all I said was ‘I LOVE IT? But that is exactly the point. I think, most of the time, books want to be loved. Literary critics indicate a book’s worthiness by practising criticism on it, by showing there is something about a book that they want to write about. And that’s what a love letter does, too; there is something about the recipient that the sender wants to write about. And when the sender is writing about a book? Then a love letter can be criticism, too.

Featured Image Source: flashbak.com.