SAM SUMMERS reviews ‘An Insignificant Man’, a documentary that uses the politics of India to reflect on the wider politics of an interconnected, disenfranchised world.

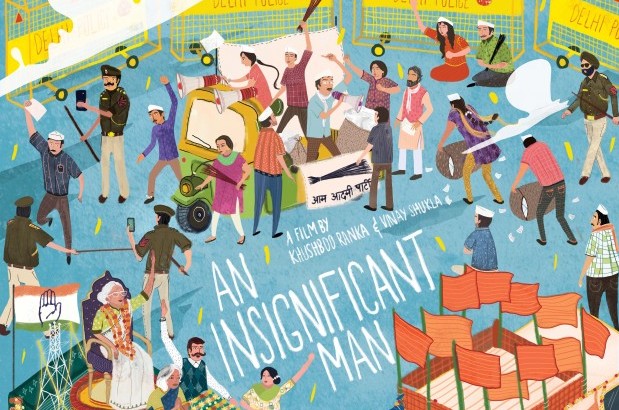

When directors Khushboo Ranka and Vinay Shukla began work on An Insignificant Man, they intended to make a comprehensive documentary on the 2013 elections in Delhi, India. Access to the leading parties–right-wing Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), and the ruling Indian National Congress–was quickly denied. Instead, they were given an unparalleled behind-the-scenes look at the anti-establishment upstarts Aam Aadmi Party (‘Common Man’s Party’). ‘We were lucky’, says Ranka, ‘it just so happened that [the AAP] ended up doing unexpectedly well.’ The film became a fly-on-the-wall look at an unprecedented, and unpolished, revolution that unfolded before their eyes.

The AAP’s participation is perhaps unsurprising, given their guiding philosophy of transparency. What began as an anti-corruption activist group morphed into a political entity in 2012, steered by former tax officer Arvind Kejriwal, who is the focal point of the film. Now boasting over nine million Twitter followers, he has become one of the most controversial figures in Indian politics; an acrimonious split from activist Anna Hazare set the tone for a political career marked by an unflinching dedication to principles. Kejriwal’s earnest yet prickly demeanour is captured in the film, which never strays into hagiography: he is man unbowed by power and wealth, irrepressible in his striving for a fair India.

Also heavily featured is AAP party executive Yogendra Yadav, a more patrician, media-savvy political player. The directors see Yadav and Kejriwal as fascinating case studies in and of themselves. Shukla argues: ‘They represent the essential dichotomy of our needs. Kejriwal is a more rusty intellectual, who can express complex balance sheets to ordinary people in a way no intellectual has managed before… Yadav comes from a certain elite intellectualism, from a deep rigour and academic understanding.’

Kejriwal’s brand of outsider politics is not an alien concept; recent screenings in Toronto have made immediate comparisons to Bernie Sanders, and the reactions across Europe will undoubtedly draw parallels to Jeremy Corbyn, Syriza, Podemos – perhaps even Trump. There certainly is much here that is familiar, not least in the way social media has invigorated the dialogue, engaging scores of young people for the first time. Old Media’s coverage of the AAP is frequently condescending, with one newscaster praising the AAP for ‘capturing the imagination’ of the public whilst the other parties secure their votes. ‘When we started filming’, says Shukla, ‘[Kejriwal] was treated with disdain by the establishment… the media is a very heterogeneous being in India.’

Yet, in the final stretch of the film, as the AAP surges past the poll’s predictions, journalists strike somewhat tragic figures against the jubilant crowds. They stare aghast at their smart phones, disorientated, as if the country’s axis has tangibly shifted beneath their feet. Shukla is keen to point out that ‘this [media] bias has been encountered by new political movements across various cultures who have subsequently gone on to win elections.’

Equally recognisable to UK audiences are the establishment voices that seek to temper dissent. In a hustings packed with AAP supporters, a slick BJP candidate wryly concedes ‘I realise the dice is loaded against me’. Yet, in the speech that follows, he persuasively preaches caution against idealistic naïfs: ‘You know what they say: revolutionaries make great lovers but terrible husbands’. Even in an openly hostile room his conservatism gains laughter and applause; the appeal of safe pragmatism is easy to see.

Whilst parallels with Western democracies are inevitable and understandable, directors Ranka and Shukla seem keen to move beyond them. Ranka points out that ‘Bernie Sanders is a career politician’, whereas the AAP is comprised of ‘complete outsiders to politics’. Shukla seem less interested in comparisons between individuals, and more in what these similarities say about the state of politics in an interconnected, disenfranchised world. ‘This is the generation we are living through: people are seeking a more direct engagement in participatory, desire-orientated politics. Of course, it’s a long-drawn out process: each country comes with its own problems; each hero with his or her own shortcomings and tragic endings. But there is a current brewing across the spectrum.’

The film deliberately moves away from the personal: as a character study, it never approaches the crotch-level cosiness of Weiner, another great political documentary of 2016. The two films share an accessible style: both are tightly edited, Hollywood-indebted productions, sound-tracked by oneiric synths, incorporating the ambient buzz of media commentary. But An Insignificant Man uses the minutiae of the election trail as an intimate study of the universal, interrogating the more macro nuances of democracy. ‘We zoomed out,’ says Ranka, ‘challenging ourselves to make sense of the human story through the political landscape and not vice versa.’

As is the case with Weiner, the film’s end point in 2013 has since been hugely complicated, as history sweeps on with little regard for neat conclusions. ‘We chose to stop filming because the AAP had ceased being activists and became politicians,’ Shukla posits, although Ranka quickly adds: ‘also, our resources had completely run out…’

Some of the events of the intervening years are documented in the film’s postscript. Most notably, Yadav had left the AAP on controversial and ambiguous terms in 2015. ‘It’s a pity, no doubt,’ says Shukla, ‘but very often it’s not them: it’s our needs. Our politicians are reflective of the society we have built together and endorsed.’ The title makes clear that the directors are not as interested in the leader as they are in the vast, complex system he has infiltrated. Their goal, Shukla articulates, was to ‘engage with the personalities of our times to reflect on our times. To not say this particular individual is good or bad, but to always try and find the narrative that brings the discourse forward.’

There is little doubt that Shukla and Ranka have succeeded in finding such a narrative. Ranka talks of having ‘grown up completely alienated from the political process, and the picture of India as a democracy’. It was never enough to say ‘it’s the biggest democracy in the world’. And yet, watching An Insignificant Man‘s bumpy but forceful conclusion, it is clear that the nation is being swept by a resurgent, powerful democratic voice.

‘An Insignificant Man’ is part of the 60th London Film Festival at the British Film Institute, taking place 5th – 16th October. More information can be found here.