LILY POUYDEBASQUE considers the exhibition of state-commissioned art in Hungary from the early 20th century, uncovering the presentations of culture and lifestyle that existed in bright colour under the shadow of war.

Budapest’s history is rich with unifications: from the marriage of Austria-Hungary, to that of Buda and Pest. Another unification stands out – one of art, glamour and lifestyle with its peoples in a forgotten crevice of history. The Hungarian National Gallery illuminated this shaded part of the last century in April of last year, through its temporary exhibition of Hungary’s posters from 1920 to 1938.

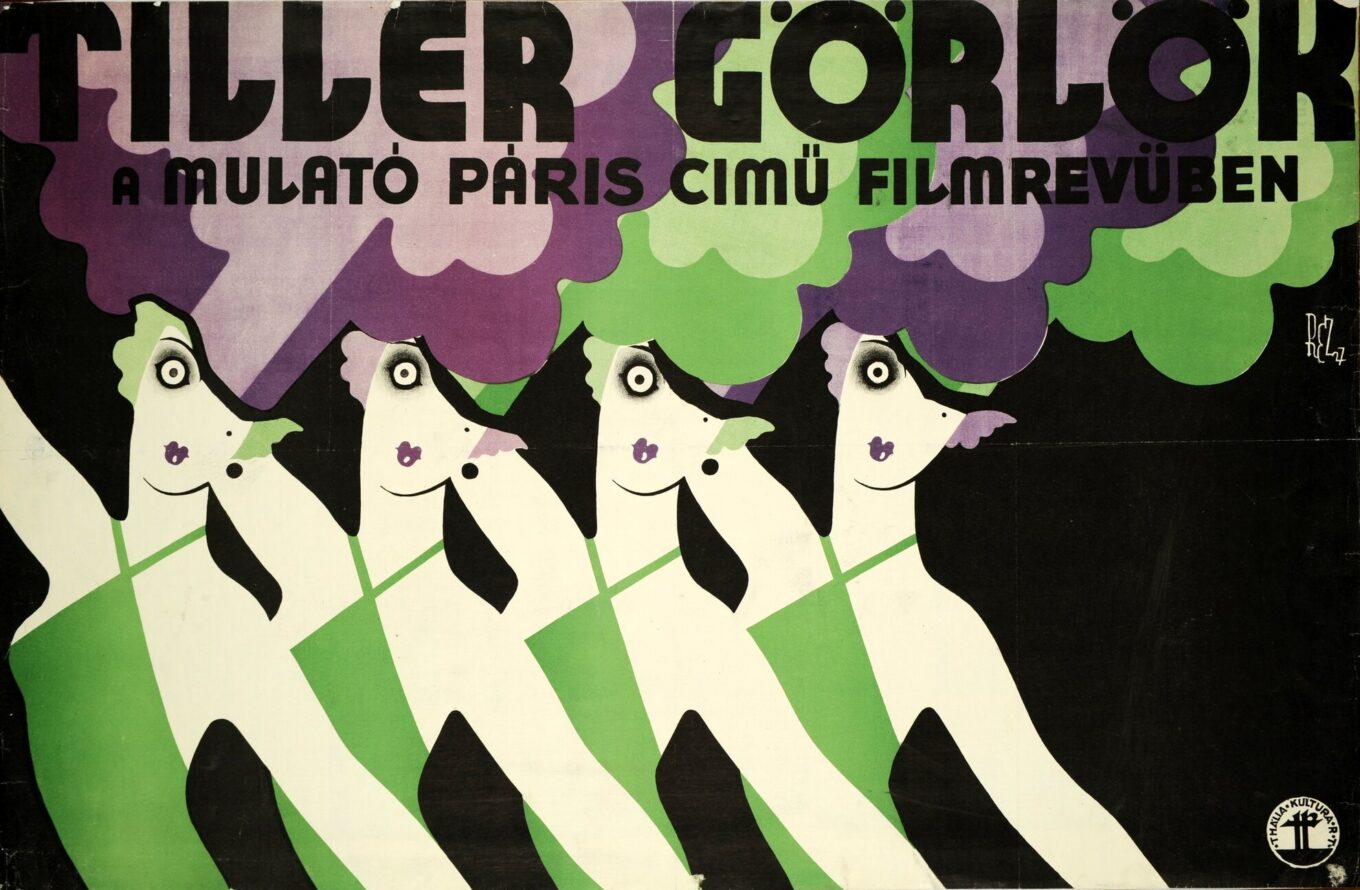

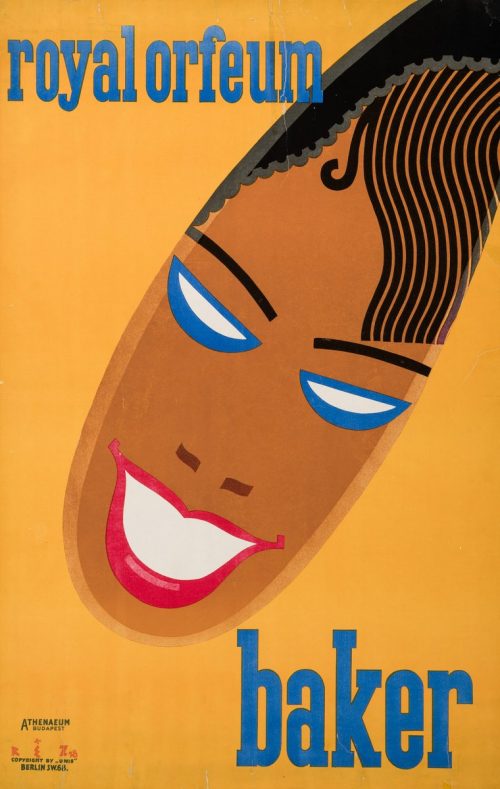

Their theme revolves around Art Deco: an art movement born in 1920s Paris, heavily based on modernism and cubism. Influenced by the French, Hungary’s posters show gorgeous seductive women, oriental furniture, and pictograms with cutting-edge symmetrical satisfaction. During the interwar period, Budapest was a burgeoning cosmopolitan city, advertised for instance by Tibor Rèz Diamond in his 1928 poster of Josephine Baker’s Budapest performance during her European tour. The glamour didn’t stop there, as the city was reputed for her water activities of bathing in the luxurious spas and the Balaton Lake, as well as her alluring fashion. The women everywhere were splendid and (appeared) emancipated, dripping in style. These posters, originating from a world unknown to me, somehow instigated a nostalgic feeling of the swinging 20s. The cubist and modernist influence create a Budapest exuding performance, style, and leading the entertainment world. With the opening of Corvin shopping mall in 1926, architectural salons, fashion, branding and other trendy things (radio!) spreading, it felt like the place to be.

As the exhibition trail unravels, I notice the change in the posters from the sway of Art Deco’s funk to ones with mundane appearances, and the imposing shadow of Nazi authority. During the Second World War, Hungary was no exception to the changing art-landscape, as creative efforts had to be halted to give way to total-war. Although the exhibition ends in 1938, as time progressed beyond that Hungary veered a significant distance away from its Western counterparts. In France of the 1960s, Yves Klein had nude women roll in blue paint and throw themselves on canvases. In 1967 in the U.S., Andy Warhol presented the Banana, a fruit turned iconic pop-art-piece. In the UK, people peed themselves when seeing The Beatles.

In Hungary, in 1956, people were being gunned down, and art was only accepted if it were a homage to the Soviet Union. The difference could not be more stark. Budapest fell from the cosmopolitan stage after WWII, replaced by the likes of Paris and New York, never to be saved or to be remembered as any kind of capital of the Arts. The victims are places such as Corvin; now a rotting place, and the migrating artists unable to see any particular interest in the country for their creative endeavours.

The self-expressive reputation of cities like Paris and London are not accidental to the politics which have shaped them – or which have enabled them to shape themselves. Budapest and her creativity has been stifled under a politically laden blanket for over a century. But that doesn’t take away from the talent of her people, their history and their potential. In fact, for this reason it was all the more important to showcase this talent at the Hungarian National Gallery; to exhibit these posters a century after their creation. One could also find it interesting that the exhibition was in a part of the Buda Castle, Orbán’s ‘home’. I believe it may also be a form of reminder of the way society cherished art, and the trajectory towards which it was heading, before being trampled by oppressive politics.

In this way Budapest can reformulate its history in the context of its modern political climate, and inspire a contemporary artistic response. It may have been a protest against the political happenings in the country today, but over and beyond this, the exhibition was a wonderful revival of Budapest’s colourful society and begs the question if, instead of politics shaping art, art could shape politics.

Featured image source: Hungarian National Gallery