AYAZ KHEZRZADEH looks at how JUKHEE KWON manipulates text as a medium for her art.

With a waterfall of old book pages cascading from the ceiling of October Gallery, Jukhee Kwon makes her intentions of telling a narrative of reinvention clear from the offset. Filling up the space with literary voices of the past, Kwon’s unique voice as an artist comes from not only echoing these voices but redefining them. Whether it is her meticulous manipulation or deliberate disembowelment of old forgotten books, Kwon’s ability to expand the experience of reading beyond its original conventions is nothing but artful.

Born in South Korea and now based in Italy, Junkee Kwon is dedicated to telling stories that are accessible to all. The books that she repurposes come from an array of languages and cultures. She achieves this all without the limitation of language, by instead portraying imposing visual scenes that all can read as impressive. The purpose of these pieces are not to read and decode the words of the pages she has reworked, but to appreciate the tactile process it took to create these pieces to begin with. This becomes a universal language in itself. In breaking down the barrier of language, she ultimately becomes ‘Liberated’ as her exhibition’s title suggests. The freedom in her artistic process allows her to locate a sense of universality to her work.

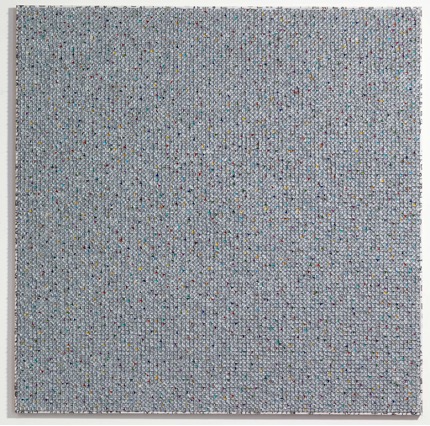

For instance, her work Paradise (2022) displays the pages of a book folded so finely on a microscopic scale that the original source becomes unrecognisable. The words of the page become minute and thus unreadable, forcing the viewer to step back from the piece to appreciate Kwon’s bespeckled work as a whole. In doing so, she tells us as viewers to observe the work on a macro, as well as a micro scale – to challenge our expectations and to act as an illusion. The infinite geometry of the piece is arguably reminiscent of the kaleidoscopic works of Damien Hirst, or even the finite portraiture of Chuck Close – reliant on the viewer and the perspective in which they are observing the work. This illusionary aesthetic Kwon portrays feels especially liberated from the confines and conventions of what we think a book should be.

In fact, Kwon’s ability to defy conventions is amplified when we look further to her 2011 piece, ART Piramide. Kwon takes Antonio Butera’s Utet and cuts a square directly in the centre of the cover – unafraid to hide where she has derived her artistic medium from. It is easy to ponder if Kwon has specific intentions in repurposing this book; why choose the old Italian legal theory of Butera as the source of your artistic work? Overtly stated and roughly cut, her message is loud and clear. A pyramid is displayed, where old pages of Butera’s work are spliced together to ultimately allow for only one word to be seen: ‘ART’. The original book is a part of the work, allowing the journey to be shown from forgotten source to now a piece of art.

Whether her choice to use Butera was intentional, or randomly picked at chance, no longer feels significant when we as the viewer see the end product. The piece of art itself speaks a new language that the book before could not. In a way, it feels almost opposite to the unrecognisable original source of Paradise. Inviting you to read closer, Kwon overtly tells you the singular word for the viewer to focus their eye on. Whereas Paradise does not have the same presence of its creator, and instead leaves it to the viewers themselves to choose where their gaze lays. Yet, both works achieve their goal in creating old from new; repurposing and redefining our ideas of what a book can be.

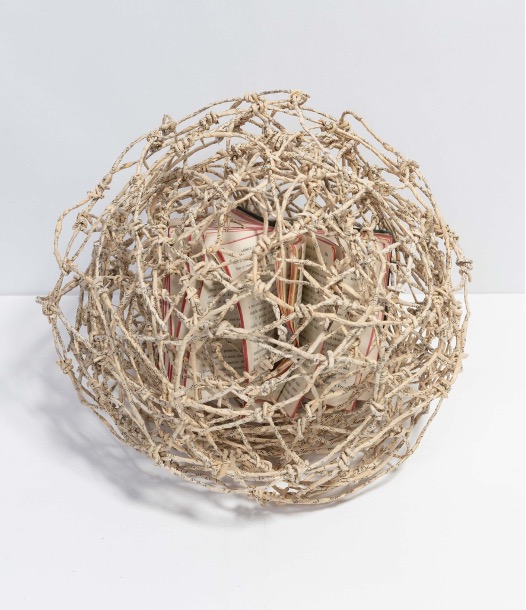

And knowing where the materials come from only adds to the connection and appreciation a viewer has to the artistic process. Kwon’s upcycling process allows for a conversation on sustainability and the revitalising quality of her work to be had. The long-existing relationship between art and sustainability has been manifested through a variety of artistic genres, mediums, and historical contexts – Kwon’s work being no exception to this. The climate crisis of today’s age warrants admiration for artists like Kwon who are conscious of the mediums they use. Her art, as well as the practices used to make them, aim to draw attention to climate change and environmental deterioration. The impressive nature of Kwon’s ‘Liberated’ exhibition is her ability to recycle old stories, to tell new ones. Therefore, Jukhee Kwon’s overall respect and appreciation for preserving books – enough to give them new life – cannot go unnoticed. Take her piece Inner World (2023), where a book is left untouched in the centre of her piece, preserved and intact. Kwon celebrates the book not just as a tool, but as a powerful entity in and of itself. The book is protected by shredded pages manipulated to look like knotted barbed wire. As a result, Kwon also aims to protect the integrity of literature, keeping it safe from being destroyed.

In recycling old stories, Junkhee Kwon is able to create new ones. She is not limited by her medium, showing the breadth and potential of something as simple as an old book. In demonstrating this breadth, she brings new life to these old books that could have easily been forgotten. Through meticulousness and tactility, Kwon redefines the bounds of literature at the October Gallery in a way that feels wholly unique to her. She takes the abandoned words of the literary past and translates them into a universal language. To understand this universal language takes no wordsmith – it takes the knowledge of understanding what these books once were to begin with, and what they will eventually be when Juhkee Kwon is done revitalising them.

Featured image: Jukhee Kwon,Oval Book Forum, 2023.