AUDREY KADJAR reviews The World Goes Pop at the Tate Modern

Should Pop Art be remembered, as Richard Hamilton’s famously defines it, as “popular, transient, expendable, low-cost, mass-produced, young, witty, sexy, gimmicky, glamorous, and Big Business”? The Tate Modern’s exhibition The World Goes Pop challenges this, showcasing a diverse, global and politically engaged ‘Pop’.

This blockbuster of an exhibition aims to expand Pop Art’s frequent associations with British and American male artists such as Andy Warhol, Roy Lichtenstein and Richard Hamilton. The World Goes Pop demonstrates that artists from all over the world reacted to their various political and socio-economic climates in the 1960s and 1970s using everyday, typically capitalist imagery. The exhibition features relatively unknown male and female artists from twenty-eight countries. By displaying an impressive amount of artworks in colourful rooms, the curators have chosen to insist on this diversity whilst alluding to the pop cliché. Though the arrangement is mainly thematic, it also focuses on particular artists from specific regions so as to illustrate the development of the ‘Pop’ movement outside the West.

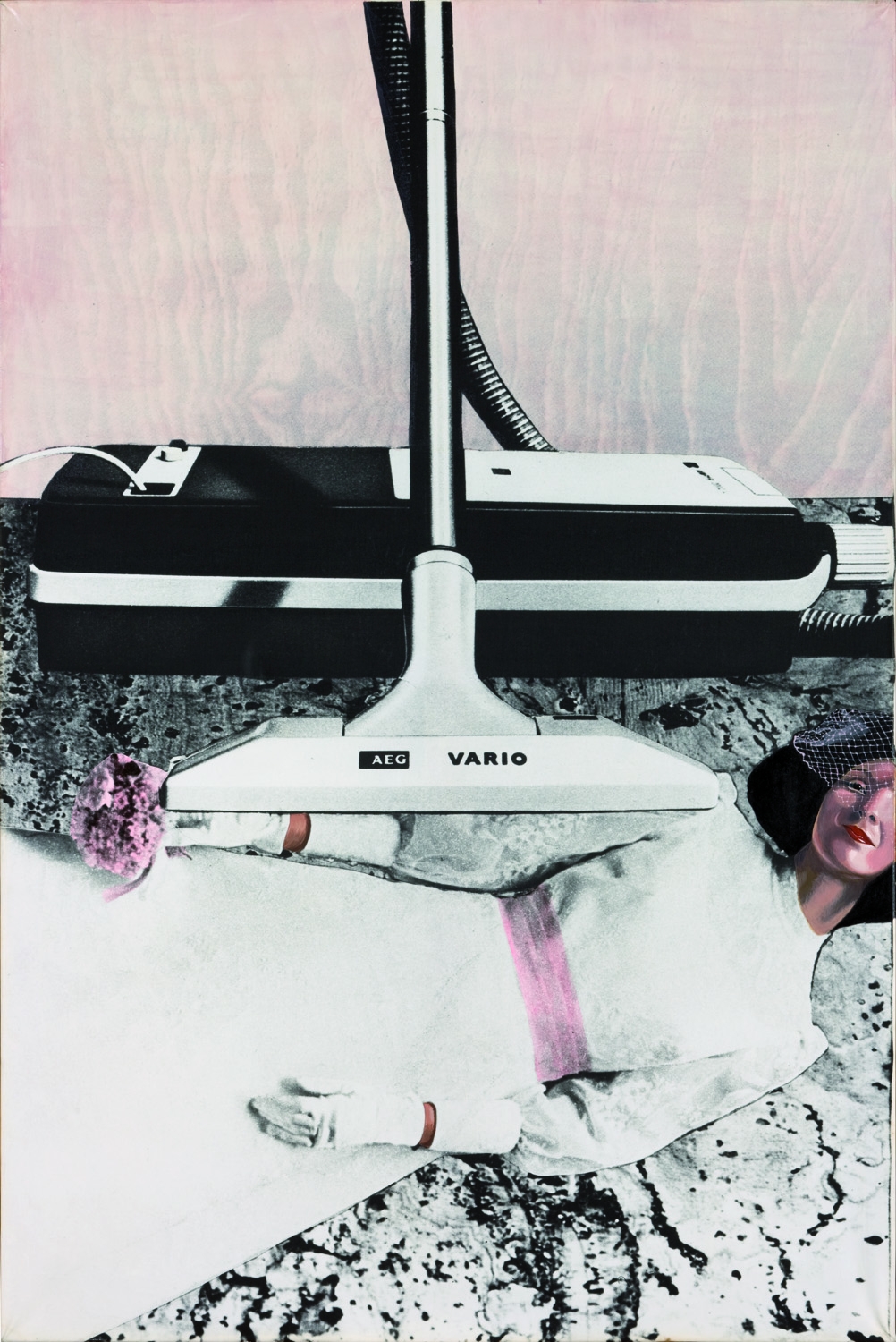

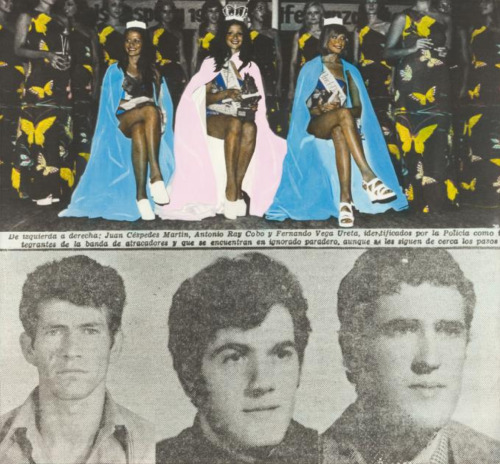

The exhibition starts by showing that ‘Pop’ pieces are not merely playful objects, but are politically engaged with the second half of the twentieth century. Japanese artist Keiichi Tanaami’s short film Crayon Angel (1975) combines images of bomb explosions and Japanese manga characters with an audio loop of heartbeats and military alarms, underlining the aggressiveness of the American invasion. Eulàlia Grau responds in a similar way; her series of collages Ethnographies (1972–3) reworks overtly glamorous press images to highlight hypocrisies within Spanish society under Franco’s dictatorship.

MACBA Collection. MACBA Consortium

The room dedicated to the Romanian artist Cornel Brudaşcu heightens the exhibition’s focus on non-Western ‘Pop’. Brudaşcu’s experiments in form and colour, exemplified in his piece Composition (1970) echo similar developments in Western art that would have permeated his and other young artists’ field of influence in the 1970s.

The exhibition also tackles feminist issues from an engaging perspective; it shows how female artists reacted creatively to the objectification of their bodies. A wonderfully sarcastic example of this is Nicola L’s thought-provoking installation Little TV woman: I Am the Last Woman Object (1969). The work sees several drawers assembled to form an abstracted female figure with spread legs, and a small television inserted between these bears the inscription ‘I Am The Last Woman Object. You can take my lips, touch my breasts, caress my stomach, my sex. But I repeat, it is the last time’

The last room addresses one of Pop Art’s central relationships and themes: the dynamic interplay between art and consumerism. In a series of fifty paintings titled Bućan Art (1972), Yugoslavian artist Boris Bućan stresses the way in which art and capitalism permeate into one another. The artist subverts iconic brands – the familiar slogans and logos retain their original typography and appearance – but the only word to appear is ‘Art’, or, in the case of his treatment of the ‘Coca-Cola’ logo, ‘Art-Art’. Ironically, a highly appropriate marriage of art and consumerism takes place here; visitors enter the exhibition’s gift shop through this final room of brand infused ‘Pop’.

A central strength of the exhibition; but, also perhaps it’s main weakness, is to be found in the sheer volume of work exhibited – large in its global scope, this exhibition can feel indigestible at times. However, ultimately The World Goes Pop succeeds in casting new light on a very familiar moment in art that has for too long been explored from only a single (notably white and male) perspective. The viewer is introduced to a complex, multi-faceted and multi-national ‘Pop’.

The EY Exhibition: The World Goes Pop is open to the public until 24 January 2016