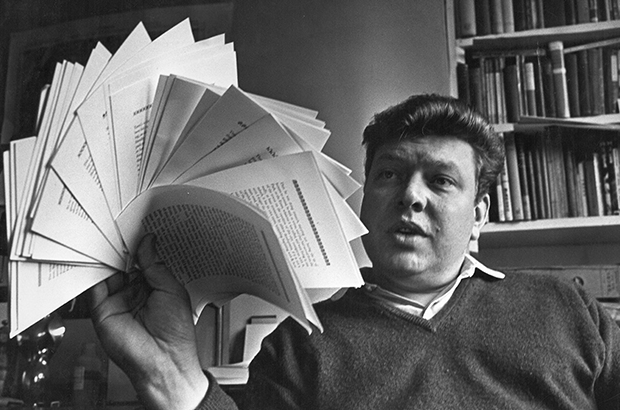

DAVID LEE ASTLEY analyses B.S. Johnson’s portrayal of an obsessively economised society in his novel Christie Malry’s Own Double Entry

Why am I writing this article about B.S. Johnson’s small book Christie Malry’s Own Double-Entry? Is it because it has been 47 years since the publication? Or is it because it has been 564 months? Or is it because 2020 is the 47thanniversary of B.S. Johnson’s death? Or maybe because this year would have been the 87th birthday of the writer? No, none of these work, they aren’t rounded, divisible by five or ten. Let’s try a different avenue. OK. Yes. Yes, maybe, maybe this could work. I am writing this article because B.S. Johnson sounds kind of like that blond mopped Tory who is

NO NO NO

NO NO

NO

These are all lies and B.S. Johnson most certainly did not like lies. Telling stories is telling lies, went the novelist’s unusual mantra. Of the seven books he wrote, six of them seemingly draw heavily and directly on Johnson’s life. Truth was his currency. In Trawl, his third novel, a passenger on a fishing vessel, while bed bound with sickness, becomes lost within the memories of a childhood and youth that mirror Johnson’s own. The protagonist sifts and searches through his memories in order to better understand the man he currently is. In what was perhaps an attempt to spur the story on as well as to more accurately describe the sensations and the sickness of sea travel, Johnson spent three weeks aboard the Northern Jewel on its voyage up to the Barents Sea. As Johnson told his publisher: ‘It is a novel, I insisted and could prove; what it is not is fiction.’

As well as a rabid pursuer of truth, Johnson is known for what most would call ‘experimentalism’, much to his disdain, clearly hearing a note of blandly British condescension. Along with writers such as Ann Quin and Alan Burns, Johnson was part of a small group of British novelists committed to the necessity of innovation, just as the Duras, Robbe-Grillet and Le Clézio had with Nouveau Roman. For Johnson, writing demanded honesty and accuracy, which he sought to achieve through his radical experiments with form. In his most successful experiment, The Unfortunates, his unbound book-in-a-box, Johnson lets the reader configure the novel in whatever manner they wish. The 27 loose chapters of the book detail the mournful memories that emerged for a writer sent on a booze-soaked and dreary trip north to report on a football match. Johnson often reported on football matches to stay in the black and the city recalls Nottingham, which had been home for one of his closest friends, Tony Tillinghast, before he had died of cancer in his early thirties. Again, ‘what it is not is fiction.’ In the randomly read, loose chapters of The Unfortunates, Johnson is able to articulate, with intensity and sincerity, the painful mechanics of memory unlike any other writer has.

Despite being an absurd and horrifying black comedy, Johnson is no less precise in his writing in Christie Malry’s Own Double-Entry than in the excruciating evocation of loss in his book-in-a-box. Indeed, much of the humour of the novel is dependent on Johnson’s ability to seamlessly intersperse the text with clauses, sentences and sections that break down the text’s artifice. To offer an example, when Christie, the protagonist, and his girlfriend, the Shrike, visit her mother, who informs them: ‘Aaaaer, it was worth it, all these years of sacrifice, just to get my daughter placed in a respectable novel like this, you know.’ Or when, in Chapter XXI, Christie and Johnson enter into a dialogue:

‘Christie,’ I warned him, ‘it doesn’t seem to me possible to take this novel much further. I’m sorry.’

‘Don’t be sorry,’ said Christie in a kindly manner, ‘don’t be sorry. […] The writing of a long novel is in itself an anachronistic form: it was relevant only to a society and a set of social conditions which no longer exist.’

‘I’m glad you understand so readily,’ I said, relieved.

‘The novel should now try simply to be Funny, Brutalist, and Short,’ Christie epigrammatised.

‘I could hardly have expressed it better myself,’ I said, pleased, ‘I’ve put down all I have to say, or rather I will have done in another twenty-two pages so surely….’

Abstracted so, these experimental passages could appear heavy handed and trite, but you will have to trust me (don’t forget you are reading this, an exercise which demands a good dose of T) or find out for yourself that Johnson ensures you don’t turn your lip or sigh over the page in response.

Like Trawl and The Unfortunates, Christie Malry’s… draws heavily on the author’s life. Similarly to Johnson, Christie comes from a working class family with little money and believes ‘that the course most likely to benefit him would be to place himself next to money, or at least next to those who were making it.’ This conviction leads him to work in a bank at the age of 17. Christie quickly becomes aware of the shadowy sculpting going on all around him and decides to become an accountant ‘in order to see where the money came from, how it was manipulated, and where it went.’ He quits his job at the bank, finds another in the accounts team of a company that makes sweets and cakes, and enrols at night school to learn accountancy. The course of these events is highly redolent of Johnson’s own path between leaving school and going to university as a mature student. The only difference, however, is that for Johnson it was the accounts department of an oil company.

At night school, Christie learns of double-entry book-keeping. This system goes back at least half a millennium to Fra. Luca Bartolomeo Picioli, the Tuscan monk who codified the method in 1494, and has dominated the world ever since. It seems to me far more than educational access that resulted in a monk formalising the system of double-entry. Every debit must have its credit – there’s a sense of religious justice, of karmic balance to it. As Christie’s mum pointedly puts it on pg. 24, before falling dead at the end of the leaf:

We fondly believe there is going to be a reckoning, a day upon which all injustices are evened out…But we are wrong: learn, then, that there is not going to be any day of reckoning, except possibly by accident. It seems that enough accidents happen for it to be a hope or even an expectation for most of us, the day of reckoning.

Let us, though, for the time being at least, like the good humans we are, focus on that other god: capitalism. Double-entry book-keeping is, after all, the most important capitalist tool ever invented. It forms the rational underpinning of the economic and social system that envelopes and organises us all: a fact lost on neither Johnson nor Christie.

On his walk home after a particularly dull and monotonous day, Christie becomes annoyed by a speculatively built office block, which he regards as dictating where he must walk and, therefore, impinges upon his freedom. With double-entry on his mind, he begins to envisage a new system: ‘I could express it in Double-Entry terms, Debit receiver, Credit giver, the Second Golden Rule, Debit Christie Malry for offence received, Credit Office Block for the offence given.’ But how, he wonders, does he settle the account? He is entitled to payment, but in what form? It’s Christie’s system, so he decides: he takes a coin out of his pocket and gouges a yard-long line into the façade of the offending office block. Account settled.

And so Christie starts totting up his debits and doling out his credits onto the world. For the office supervisor’s lack of sympathy, Christie is debited £6.00. For the unpleasantness felt by the presence of a reverend, £0.04. For balance, Christie destroys an important letter for his supervisor and sends another to the council complaining about the grammar of the reverend’s leaflet. But as time continues, the sources of Christie’s debits widen, growing progressively larger and larger. For the trauma of childhood education, £35.00. The general diminution of his life by advertising, £50.00. For the exploitation of a month’s labour, a further £200.00. Christie’s actions try to keep pace, becoming more extreme, more sociopathic, until, well, they become murderous.

It all reaches a head, though, in Chapter XVII, when he decides to poison a reservoir. This leads Christie to ask himself: ‘am I not overdrawn? What wrong has society done me that I can offset more than twenty thousand deaths against it?’ In his final reckoning, Christie is credited £26,662.70 based on a rate of £1.30 per head of the 20,479 dead, and debits himself a hefty £311,398.00. The reason: socialism having not been given a chance.

£££££

On my way home after buying Christie Malry’s… for a friend’s birthday, I thought: Yes, it’s a horrifying black comedy, but how much of an extrapolation is Johnson’s novel, really? In which shade of grey do we exist? Aren’t the lives we lead subsumed each day to such abstract accountancy? And, I thought, most depressingly, how often are we – you and I – are culpable of falling into such capito-nihilistic logic, like the novel’s namesake? ‘In the image of yourself, Christie is, remember.’

Hopefully the rhetorical device of these four questions did the job of bringing forth some memories, once-read articles or other related experiences to wash this world of endless economisation and monetisation with some personal colour. But if it failed, let me reiterate: There seems little left of our lives or the world around us that is not already captured by the power of the pound and profit. And where there remain glimmers of non-capitalist existence, there is a man, always a man, somewhere, dreaming and scheming of how to make it not so. Nothing has merit in and of itself, but solely through systems of confused and crooked accountancy. Health and care buried beneath cost-benefit analysis. Education dictated to by metrics of employability and earning outcomes. The knowledge economy. Culture must provide a return on investment. The world heads to environmental and societal crisis and the necessary action is deemed just too expensive. They drown and burn and flee, while we comfortably wait for the manna of market-based solutions.

In writing this, I briefly flicked through the greys and blacks of the Pantone Colour Matching System, in hope of assigning our world and time a suitable colour in comparison to the blackness of Christie Malry’s…. But then, embarrassingly, I remembered that one was actuality and one was a book, a 47-year-old book, and perhaps the attempts at a humorous tone should stop. What compounds the despondency of this comparison is the knowledge that Christie held some sources of his life dear, which he omitted from the debits and credits. In our world, however, this omission is impossible, as everything we hold dear is happily accounted for. The death of Christie’s mother, his love of the Shrike represented areas ‘in which the writ of Double-Entry did not run.’ Which algorithms benefitted from the depression that followed my mother’s early death? How is her life factored into the calculations of the economic impact of some illness or another? What are the tech giants’ collective profits from the loneliness that they exacerbate? How much did Purdue Pharma make from the pain inflicted by capital? There are now valuable margins and saleable insights, depressingly, within each of these most human moments. We are merely labour, consumption and a melange of traumas and exaltations with reciprocal sets of margins. Living, dying, working, fucking, crying – it’s all the same, it’s all profit.

Are we, therefore, arriving at the answer as to why I wrote this article about a small book from the 70s? The jewel of journalism, the continuing commission: prescience? I’m sorry, world, tiny readership, but I’ll have to say no; B.S. Johnson was not prescient, he did not write our today and nor does he offer us any hot takes. The dead experimentalist did not foresee Thatcher and Reagan and the onslaught of neoliberalism. He did not envisage our tech overlords. Instead, just like those Transatlantic leaders did, Johnson extrapolated the logics of capitalism that already ensnared him (and Christie) in 1970s Britain, the one in which the Angry Brigade were chucking their bombs.

In the novel, the binds are so tight that Christie is left with only one option: play the system at its own game in hope of finding some sort of justice. The problem, though, is that justice will never arrive: neither for the protagonist, nor for us. As you move through the book, his actions becoming increasingly extreme, even the feeling of justice dissipates. Christie’s steps take him closer and closer to the end, they slow, they sway and stumble, they fall off the path. The pace dampens as the cancer spreads, towards the reckoning, and Christie murmurs onto the page: ‘all, all pointless.’

‘At least your Great Idea prevented you from becoming bored to death with life,’ I told Christie when I paid what he must have seen as my last visit to him.

‘Of no concern now,’ replied Christie, weakly.

At the end of an unnumbered page of delicate evocation – ‘His average eyes appeared sunken, ringed with yellow-brown; his average cheeks had sunk, too. The general feeling about Christie is one of sinking’ – Christie dies of pneumonia, death rattling the book to close. But before it does, the final accounts must be settled: £352,392 is written off as bad debt and that is that.

In the few scraps of fragile text that make up the final pages of Christie Malry’s…, Johnson is able to underscore his humanity as a writer. He riled, melancholic, against a world that cares little for the preciousness of life – the sanctity of it, to borrow the language of the Tuscan monk. Though I doubt Johnson, a man who declared all chaos, would particularly appreciate the monk’s religious leanings, I doubt little the distress that they would share at the continuing evisceration of life to capital, at a world in which life be but a ‘very inexpensive, plentiful and easily-disposable asset.’ What compounded Johnson’s distress at capitalism’s ceaseless hatred for life, was the socio-political and electoral situation that supported and sustained it. In two sentences that cry even truer today in a UK of growing debt and working hours and reducing security and real wages, where another Johnson sits in Downing Street, B.S. Johnson was able to succinctly distil the political condition that meets us each and every fucking morning in Christy Malry’s Own Double-Entry:

Lots of people never had a chance, are ground down, and other clichés. Far from kicking against the pricks, they love their condition and vote conservative.