DAVID LEE ASTLEY considers Gordon Burn’s scintillating true-crime classics, Somebody’s Husband, Somebody’s Son and Happy Like Murderers.

Gordon Burn is best known for his penetrating studies of Peter Sutcliffe and Fred and Rose West, in Somebody’s Husband, Somebody’s Son and Happy Like Murderers. While his novels sought to capture the blurring of lived realities and accordingly melded fiction and nonfiction. In these books, however, Burn vividly approaches the definite, however devastatingly appalling. From the fictions that had been crafted in the wake of the murders, for the purposes of headline splash and societal comfort, he sought to reclaim the actualities of the crimes of Sutcliffe and the Wests. While both books read almost like novels with the precision and movement of Burn’s writing – no reader of Happy Like Murderers will easily forget the West Country vernacular of Fred West that seeps out of the page – one never wonders whether the truth has been stretched or eschewed.

This trust between the reader and the writer develops easily and unquestionably in the two books. Burn never bluntly signposts his sources and evidence, instead it flows seamlessly through the texts. He deftly weaves in discussions with relatives and passers-by, police interview transcripts, local papers and archives with a narrative grounded in these sources and many more. It is only in the acknowledgements of Somebody’s Husband, Somebody’s Son do we learn, little surprised, that Gordon Burn lived in Sutcliffe’s hometown, Bingley, for over two years to prepare the book, growing close to the serial killer’s family in the process.

Gordon Burn does not seek to authoritatively explain why Peter Sutcliffe or the Wests committed the crimes they did, nor does he seek some simplifying, psychological rationalisation that may reassuringly other them. In all their excruciating detail, Somebody’s Husband, Somebody’s Son and Happy Like Murderers decisively re-embed the three of them and what they did within their social networks – whether that is the family, the workplace, the local community, or the country. In the case of the Wests, we learn of the incest that Rose suffered at the hands of her father from childhood to adulthood, and how this was perpetuated by Fred upon their children. We learn of the men from down the pub who would come to Cromwell Street for a visit to Rose’s room, or to watch one of Fred’s blueys. We learn of the young and often vulnerable women who would pass into the grips of the husband and wife, the physical and sexual abuse they suffered before they were dismembered, buried, concreted over and lived over by the West family.

While not deserving in and of itself of celebration, Burn’s efforts, especially in Happy Like Murderers, to properly investigate and offer voice to the women who suffered at the hands of Sutcliffe and the Wests are significant. True crime as a genre, after all, still often does a serious disservice to victims, especially women. For instance, the opening chapter of Happy Like Murderers offers a 30-page summary of Caroline Owen’s family history and her early life, up to the time she became a nanny to the Wests’ children. She escaped after recieving a horrific and sustained sexual assault from both the husband and wife, her mother reporting the crime that led to the arrest and charging of the pair. In court, Fred and Rose pleaded guilty, each only receiving a £50 fine. They would go on to murder nine more women.

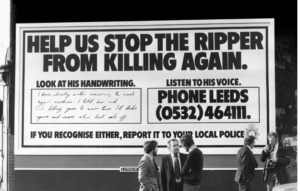

Similarly, in Somebody’s Husband, Somebody’s Son Burn documents the five-year, blundered police investigation into the Yorkshire Ripper, exposing the sexist and classist presumptions that stalled and stymied the process. Similarly to Liza Williams’ excellent BBC4 documentary on the murders,

, the book draws out the connivance of wider society in these murders. It focuses on a society that both disregarded and explained away the abuse and murder of certain women, dynamics which holds as true in the case of the Wests as in that of Sutcliffe. Through the gruelling and haunting research and writing, Burn does us a service in authoring these two books – they exist as testaments to the victims, the crimes, and to the societies that produced them. It is for this last reason that it is often remarked that Burn digs into our shared earth, exposing the dank rot of our structures of socialisation and being. It’s striking that on finishing Burn’s book on the Yorkshire Ripper, one is haunted further by the inexplicable normality of Sutcliffe in so much of his life. How different was…? Wasn’t that what…? How alike is…? These are the questions that Gordon Burn leaves us to answer.

In the autumn of 1996, 25 Cromwell Street, the home of Fred and Rose West, was demolished. Where the house used to stand is now a pathway connecting two residential streets. The rubble was quickly removed, the council wanting to ensure that nothing, not a trace, was left of the site. It was as if the council were acting to remove the house from the collective memories of the community and the country, relinquishing us of some psychic energy entombed in the bricks and mortar.

The demolition exemplifies the concerns of memory that so occupied Gordon Burn’s writing. What is it that we remember, what is it that we forget? Which structures and forces such processes? What is it that we actually remember, the truth or some invention? How practicable even are those categories? Who is the Alma Cogan, the Myra Hindley, that lives on in our collective memory, and who created them?

In posing these questions, I recalled the shadowed figure of Margaret Thatcher that lives, at a distance, on the pages of Born Yesterday, Burn’s final book. In the novel, Burn spots her across Battersea Park as he walks his dog. The now reclusive figure is taking the air, her security detail hovering as she walks, with trepidation, along the riverside. She looks out onto London, the capital of the country she had so significantly crafted, and is perplexed. Deregulation and hedonism, power and constraint, unfettered liberalism and unapologetic conservatism – the contradictions, all of them hers, all of them still so paramount. Yet could she make sense of the world she saw before her that summer, the summer when the hunt for a missing young girl called Maddie became the nation’s favourite soap, the one Burn attempts to capture with Born Yesterday in all its tumult?

Most likely not, but then nor can we. We require distance, a withdrawn perspective, that is un-afforded to us in the realities – ever accelerating, ever mutating and mutilating – that we are enveloped in and envelop ourselves in. Gordon Burn had a gift for being able to begin to reach such perspectives earlier than most and, most importantly, of offering them to us, his readers, with beautiful clarity. To take a final example, in 2011, the last days of his life and only shortly after her own death, Gordon Burn was researching Jade Goody. Some eight years later, the significance of Jade Goody was explored by Channel 4’s documentary series Jade: The Reality Star Who Changed Britain. The documentary sketched Goody as a totem for these most speculative days, ones in which we are bombarded by unrelenting reality television and proliferating influencers, subsumed to the desires of unreformed finance, and governed over by a comic creation. One can’t help but feel that Burn would have come to the same conclusions of Goody as an emblem for our today, a lodestar for 21stcentury Britain, and articulated, as he so often did, what lay hidden before our feet.