NICK FERRIS review Custody at Ovalhouse.

Since 1990, 147 BME people have died in police custody in England and Wales, yet there has not been a single prosecution for homicide for any one of them. Aiming to draw attention to the injustice that this statistic belies comes Custody, a new play by South London performer Urbain Hayo — stage name Urban Wolf — and writer Tom Wainwright, about the experiences of the family of a fictional black British man who dies at the hands of the police. Strident and angry, Custody demonstrates real depth in its characterisation of Brian’s family and powerfully explores this moment of trauma and its complex afterlives, visualising a story we hear all too often of black bodies brutalised and destroyed with no official response.

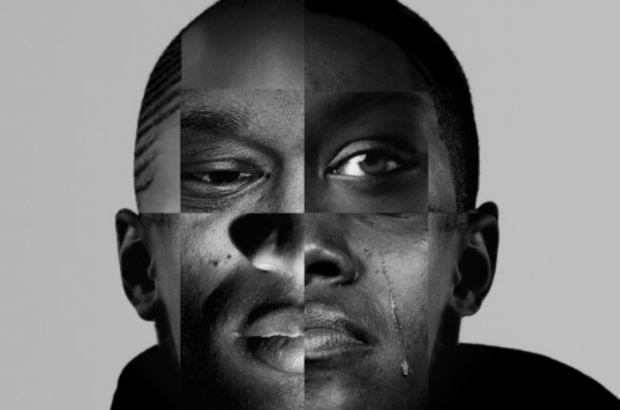

Brian is intelligent, engaged to be married, and driving his BMW when he’s stopped by police, presumed to be a member of some gang, and accused of stealing his own car. ‘A scuffle’ then follows in which Brian is killed and his family is left bereft. We never actually see Brian, and his conspicuous absence highlights how his representative story can be transposed onto countless others who have suffered for the same racially-motivated reasons. Yet at the same time, and almost paradoxically, Brian is also offered as a scope through which the audience can see a real person and individual behind statistics, a character and personality that is realised through the interactions and conversations of his family following his death.

The play is first of all a study in grief: a ring of funereal flowers and mementos surround the stage, and the set’s moving white walls are dynamically used to express and incubate in the audience feelings of suffocation and exasperation, while tightly-choreographed metaphorical vignettes are also played out to show Brian’s family’s angers and frustrations. Brian’s sister becomes politicised in her grief, joining Black Lives Matter demonstrations and fighting (in vain) to have Brian’s death deemed an unlawful killing. Brian’s brother, struggling to process and engage with his emotions, feels a guilty pride that Brian — ever lauded by his family as the morally and intellectually superior brother — should die as a result of societal prejudices for which he himself, as a small time drug-dealer, might seem the more likely target. Brian’s fiancé feels anger and a sense of injustice after Brian’s relatives close ranks and cut her off, despite her being the one that knew him best. Yet the most palpable and all-consuming grief is shown in Brian’s mother, played with great dignity and emotional depth by Karlina Grace-Paseda. She is haunted by her memory of him, coming to her in dreams as a ghost – a spirit lost and unsettled, brutalised by a society that would never fully embrace him.

Beyond its important story of suffering, Custody deals with themes of identity and contradictions and questions that come with being black in Britain today. The four actors play their characters in the present, past and future – but also in turn act as Brian in memories, or act in unison to convey shared ideas or emotions. This cluster of interwoven expressions comes to form one collective whole, living and breathing – a figuration not only of identity, but also a demonstration of a shared sense of community. All four characters are nameless, framed by the play in a police-eye view: they are inevitably viewed as the same gang member, drug dealer or thief in the prejudiced eyes of the judicial system.

Yet Custody shows exactly the contrary through the great divergence in attitudes that the four characters express. Both brother and sister are concerned with the present, proudly rebelling in their respective ways by participating in organised demonstrations or by dealing drugs. Brian’s mother turns from her Christian faith to look to the past and to the spiritualism of her ancestors, scorning the religion of a society that has treated her and her family with such injustice. Brian’s fiancé — whose family have been British for several generations, and who does not feel the same ties to her distant ethnic roots — marries a white man. This character ending — presented somehow like she abandons the struggle in favour of “integration” — problematically explores difficulties of interracial marriage in a stubbornly prejudiced society, seemingly without hope of justice for black communities.

Custody pulls no punches in its portrayal of brutal inequity and prejudice, corruption and cruelty in British systems of power. The pathetic police euphemisms of a ‘scuffle’ and a ‘passing away’ haunt the script, as they are repeated with an anger that goes beyond the patronising ways the British police justifies its injustices.

The play ends with all the major characters standing framed together, having laid aside differences in a show of solidarity for Brian’s memory, and for their community generally, in order to come and watch Brian’s brother give a speech at a Black Lives Matter demonstration. It is an optimistic note to finish on, though one tinged with doubt given the fact we have seen such variety of experiences and attitudes which have all demonstrated how, while this is an important and moral struggle, it is not a simple one with a clear resolution, and it will not alleviate the pain that has been suffered. The final tableau is both optimistic in its solidarity, but also tragic in its vision of irrecoverable loss.

The Art Machine’s Custody is running until 8th April. Find tickets and more information here.

Featured image courtesy of http://www.ovalhouse.com/